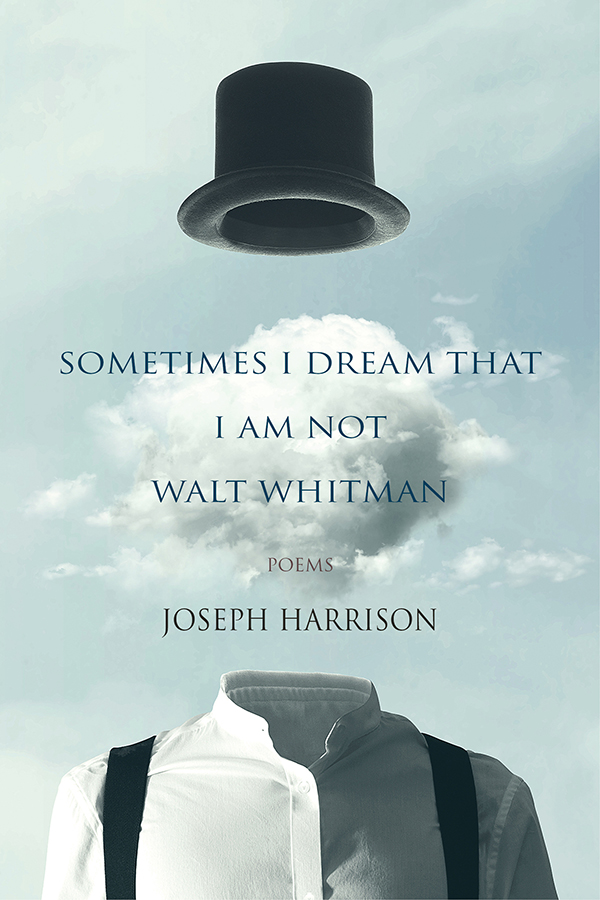

Sometimes I Dream That I Am Not Walt Whitman

Publication (US): March 15th, 2020

Publication (UK): October 15th, 2020

£10.99

In his sixth book of poems Joseph Harrison further refines his already agile art. His characteristic metrical and syntactic ingenuity are on display here again, as is the surprising capacity of his figurative imagination. Poems in a variety of forms, some elaborate and nonce, display a range of mood, mode, and matter: there are political poems, ekphrastic poems, poems on the metaphoric implications of scientific terms. At the heart of the book, though, is an astonishing advance in Harrison’s explorations of intertextuality: these poems risk a kind of poetic shamanism, a lyric ventriloquism that channels the voices of precursors American and English. The uncannily resonant music that results is both his and theirs, contemporary and traditional, idiosyncratic and familiar. Joseph Harrison has written a book that challenges our notions of poetic identity, a book where the present and the past sing to each other, and to the future.

Out of stock

Sometimes I Dream That I Am Not Walt Whitman

Advance Praise for Some Times I Dream That I Am Not Walt Whitman

We are at a moment in the history of literary culture when traditional standards of clarity, eloquence, aesthetic splendor, refined comedy, and civilized pathos have been set aside. I read a great deal of contemporary poetry. Not many volumes hearten me, this one does. The Walt Whitman poems catch him as only Pessoa / Campos does. The Charles Dickens poem brilliantly exemplifies what John Ruskin meant when he talked of Dickens’ ‘stage fire’. ‘Mark Strand’ returns me to my own dreams about my late friend. Best of all is ‘Shakespeare’s Head’, an achieved phantasmagorial of permanent power.

— Harold Bloom

In his brilliant, entertaining, dark, and companionable new book, Joseph Harrison, one of American poetry’s best kept secrets, channels the voices and spirits of dead poets as wide ranging and diverse as Mark Strand, Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens and Walt Whitman himself. But Harrison never merely ventriloquizes these and other voices; or if he does the ventriloquism, as he implies in his amazing sequence, ‘The Compromised Ventriloquist’, is reciprocal—such that, as he says elsewhere in the book, ‘every transformation / Becomes another act of self-creation.’ This book obliterates the dichotomies of self-expression and impersonality, personal disclosure and self-effacement, tradition and innovation. In the place of such facile and misleading oppositions Harrison has written a book that engages the particularities of our moment with a hawk’s eye view of linguistic, metrical and cultural history. The imagination that animates these poems is intimate and vatic, prophetic and mundane, scientific and fantastic; the music is all his own yet everyone’s, ‘dark and deep / And cold as interstellar night while unforgettably humane. I love this book.’

— Alan Shapiro

In Joseph Harrison’s hands, verse is an art, a living art, and a generous one. ‘The dead keep singing,’ he writes in ‘River of Song,’ and they do in the lyric ventriloquism through these pages: Frost, Auden, Stevens, Dickinson, Baudelaire, Hardy, Shakespeare, and most surprisingly, Whitman. Harrison’s tight forms gesture toward psychic volcanos and hurricanes, and his rhymes deploy lethal wit, as in ‘Runaway Blimp,’ about a military-industrial boondoggle where ‘a multi-billion dollar clusterfuck’ clicks with ‘run amok.’ His dexterities don’t just serve satire; the poems play a wide scale of feelings: tenderness, wonder, wry meditation, indignation, and fury. A selfless book, in the best sense.

— Rosanna Warren

His suite of cannily resonant imitations of the good gray poet notwithstanding, Joseph Harrison is indeed not Walt Whitman, nor does he seek to be, but his verse responds eloquently to the ardent prediction in Democratic Vistas that the ‘highest poems’ to come would spring from ‘the assumption that the process of reading is … in the highest sense, an exercise, a gymnast’s struggle.’ Harrison’s intensely wrought poems reward the reader well beyond the demands they make. Ebullient yet concentrated products of an audacious prosodist and syntactician, an exhilarating logophile and a master of tone, they evince a maker’s maker. A set of poems in Emily Dickinson’s mode balances the Whitman suite, and Frost and Stevens, Yeats and Auden and Merrill ghost happily through this volume, itself a ‘unity of network.’ It compasses ‘structures of posed placidity’ — structures that arise, we come to know, from an ‘intemperate liquidity / Whose outbursts, unpredictable, reveal / A flare for the dramatic.’

— Stephen Yenser

Reviews of Some Times I Dream That I Am Not Walt Whitman

Expansive Poetry Online: A Journal of Contemporary Arts (2020)

Wit is not a mainstay of contemporary poetry and we are the poorer for it. Wit is often reduced in the popular mind to mere cleverness, as if cleverness in itself seemed a thing to distrust. We are surrounded by lies, but they are not clever. But wit has more to it than cleverness; in the hands of a poet like Joseph Harrison in his latest collection, Sometimes I Dream That I Am Not Walt Whitman, wit is a humanizing force, one that is worthy of calling on those resources born of the civilizing spirit and capable of resonance and depth.

Sometimes I Dream That I Am Not Walt Whitman [Sometimes] is Harrison’s fourth full length collection … Each collection has its own logic, though the voices in them are unmistakably Harrison’s.

The plural in the previous sentence is deliberate, for Sometimes … is filled with voices. Indeed, the collection is replete with allusions, and Harrison is a master ventriloquist as well as a gifted poet in his own voice, or voices. One section is given over to the voice of Walt Whitman, another to Emily Dickinson, the two great literary forebears of modern American poetry; in the former sequence Whitman calls on Álvaro de Campos, one of Pessoa’s noms de plume. Also appearing as either voice or subject are Frost, Hardy, Dickens, Strand, Stevens, Swinburne, Shakespeare (at least his head) as well as the painters Giotto, Velázquez, and Cézanne.

Art is, in many ways, a dialogue with the dead as much as with the living. Much effort is spent by apprentice poets on developing a voice. Harrison might ask, ‘Just one?’

Harrison is also a master of form, both received and nonce … But the poet is also a master of syntax. To cite two obvious examples: ‘Dickens on Fire’ is a poem that deals with the frantic, all-consuming life of activity led by Dickens. The poem consists of eleven stanzas of fifteen lines each. All stanzas are the same form with an intricate rhyme scheme and lines measuring from monometer to pentameter. Through the mad rush of events the poem describes, one notices only in retrospect that the 165 lines are but one sentence. On the other hand, ‘Late Autumnal,’ dealing with the slow fading of the season, has seventeen sentences (admittedly some fragments) in its eleven lines. Harrison’s pacing from poem to poem is superb.

Sometimes is unlikely to be widely reviewed or nominated for many prizes—it is probably too literary for an unlettered audience and more concerned with the politics of identity than with identity politics. It is a complex book whose concerns can only be all-too-briefly sketched in a short review. But even though a few months of this unfortunate year are left, I doubt we will see another book in 2020 as good as this one. Indeed, Joseph Harrison is one of our finest poets, and it is high time he’s recognized as such. — Robert Darling (The whole review can be read by clicking on the following link: http://www.expansivepoetryonline.com/DarlingOnSometimesIDream.html)

Selected Works from Sometimes I Dream That I Am Not Walt Whitman

Mark Strand

When I came to the end of the dream, there was Mark Strand.

We were in a vast hall, where the ceiling was too high to see,

And the light slanted down from above, and a cold wind blew.

We sat on a bench in the back. A little ways off,

A teacher was teaching a class, and she asked him to speak,

But he shook his head: he was too tired. Then he turned

To me, and he said, “I don’t write anymore. I don’t

Even look at the moon. But I read.” Then he smiled. “When you read

The books you most love for the last time, you see

The great works of imagination get better and better.

When you come to that passage where, arrayed in battalions,

With all their flashing armor and flapping banners

And bright wings fanning the starlight, the heavenly host

Throws down its spears, you wonder, although you’ve read it

A hundred times, ‘Will it really happen again?’,

And when it does, you are surprised.” There were tears

In his eyes as he said this. But were they tears of sadness,

Or tears of joy, or were they just caused by the wind,

That cold wind blowing and blowing? Then he was gone,

And the teacher was gone, with her class, and the students’ voices,

And all I could hear in the hall was the sound of the wind.

Joseph Harrison

The Compromised Ventriloquist

1

Gastromancy, vibration in the gut

Tuned to the presence of the dead,

Possessed the medium to utter what,

Digested, triggered hope or dread

In questioners delighted or aghast

At all they thought they finally knew.

To tell the future or reveal the past

Was dangerous. The darkest clue

Doomed sacrificial youths and beasts.

Dim ravings, guttural, abrupt,

Translated to hexameters by priests

In versions polished and corrupt

Proved riddles no less difficult to crack.

The truth was rarely clear or kind.

Cautious Lysander wound up stabbed in the back,

Croesus conquered, Oedipus blind.

2

What once was supernatural decree

Became, in time, a party trick

Crowds at the music halls would pay to see.

The animated dumb sidekick,

Charlie McCarthy, Sailor Jim, or Coster Joe,

Though just a cheeky, wiseass puppet,

Would show his straight man up throughout the show,

Flip every quibble and one up it.

Oracular enshrinement? Oh so past.

Ventriloquy was entertainment.

Magic was stagecraft, voice the artful cast.

Nobody wondered what the strain meant.

3

Nearing the scribbled end, he took the stage,

The compromised ventriloquist,

His bare-bones theater the haunted page.

Obscurity, “uncouthe unkiste,”

Held no protection from the talking dead.

No charm or curse could exorcise

The choir of sirens singing in his head

Inspiring another exercise.

His “own distinctive style” at last? Dream on.

Some stuff he made up, sure. But then

Those ghostly demarcations would stream on

Flooding his studio again

To wash him up and out and down the drain.

Too influential, they impressed

And he was pressed. But why complain

About not being self-possessed?

Conspiring to imprison him for years,

Through harmony and ornament

The arch conductors of the crystal spheres

Abused him as their instrument.

Black magic? Maybe. Cheating? Well, that too.

Who’s talking? Uh oh. Hold the phone.

He was the dummy they kept speaking through

In words that were and weren’t his own.

Joseph Harrison

Excerpts

Selected Works from Sometimes I Dream That I Am Not Walt Whitman

Mark Strand

When I came to the end of the dream, there was Mark Strand.

We were in a vast hall, where the ceiling was too high to see,

And the light slanted down from above, and a cold wind blew.

We sat on a bench in the back. A little ways off,

A teacher was teaching a class, and she asked him to speak,

But he shook his head: he was too tired. Then he turned

To me, and he said, “I don’t write anymore. I don’t

Even look at the moon. But I read.” Then he smiled. “When you read

The books you most love for the last time, you see

The great works of imagination get better and better.

When you come to that passage where, arrayed in battalions,

With all their flashing armor and flapping banners

And bright wings fanning the starlight, the heavenly host

Throws down its spears, you wonder, although you’ve read it

A hundred times, ‘Will it really happen again?’,

And when it does, you are surprised.” There were tears

In his eyes as he said this. But were they tears of sadness,

Or tears of joy, or were they just caused by the wind,

That cold wind blowing and blowing? Then he was gone,

And the teacher was gone, with her class, and the students’ voices,

And all I could hear in the hall was the sound of the wind.

Joseph Harrison

The Compromised Ventriloquist

1

Gastromancy, vibration in the gut

Tuned to the presence of the dead,

Possessed the medium to utter what,

Digested, triggered hope or dread

In questioners delighted or aghast

At all they thought they finally knew.

To tell the future or reveal the past

Was dangerous. The darkest clue

Doomed sacrificial youths and beasts.

Dim ravings, guttural, abrupt,

Translated to hexameters by priests

In versions polished and corrupt

Proved riddles no less difficult to crack.

The truth was rarely clear or kind.

Cautious Lysander wound up stabbed in the back,

Croesus conquered, Oedipus blind.

2

What once was supernatural decree

Became, in time, a party trick

Crowds at the music halls would pay to see.

The animated dumb sidekick,

Charlie McCarthy, Sailor Jim, or Coster Joe,

Though just a cheeky, wiseass puppet,

Would show his straight man up throughout the show,

Flip every quibble and one up it.

Oracular enshrinement? Oh so past.

Ventriloquy was entertainment.

Magic was stagecraft, voice the artful cast.

Nobody wondered what the strain meant.

3

Nearing the scribbled end, he took the stage,

The compromised ventriloquist,

His bare-bones theater the haunted page.

Obscurity, “uncouthe unkiste,”

Held no protection from the talking dead.

No charm or curse could exorcise

The choir of sirens singing in his head

Inspiring another exercise.

His “own distinctive style” at last? Dream on.

Some stuff he made up, sure. But then

Those ghostly demarcations would stream on

Flooding his studio again

To wash him up and out and down the drain.

Too influential, they impressed

And he was pressed. But why complain

About not being self-possessed?

Conspiring to imprison him for years,

Through harmony and ornament

The arch conductors of the crystal spheres

Abused him as their instrument.

Black magic? Maybe. Cheating? Well, that too.

Who’s talking? Uh oh. Hold the phone.

He was the dummy they kept speaking through

In words that were and weren’t his own.

Joseph Harrison