Anthony Thwaite in Conversation with Peter Dale and Ian Hamilton

£9.50

A 96 page book, containing a 30,000 word interview, with a career sketch, a comprehensive bibliography, and a representative list of quotations from Thwaite's critics and reviewers.

Between The Lines

The latest number in the enjoyable series of interviews with poets published by Between The Lines.” – J.C., TLS, 1999

– X.J. Kennedy

“Wonderful shop talk! And much more.

The questioners and interviewee exchange quips and engage in shop talk … Thwaite’s remarks are fascinating.

– Don Share, Essays in Criticism, October 2000

Do you see the establishment of residences for poets in education and commerce – poet in residence to Marks and Spencers, say – as a wholly good thing for poetry as you know it?

I don’t know about ‘wholly good’ … I mean, I’m aware of the American example, which Dana Gioia rightly goes on about, whereby you have a whole posse of poets who simply journey from one ‘creative’ post in a university to another. They construct massive CVs full of their publications, and they help make up a sort of incestuous professionalism. But I can’t see much danger of that happening in this country. I do think we should have more residences, in universities and schools, and maybe elsewhere, than we do have. In fact the Royal Literary Fund (I sit on its committee – it gets hundreds of thousands of pounds a year from A.A.Milne – Winnie-the-Pooh) – the RLF at this moment is looking into a comprehensive way of helping set up and fund a lot more residences for writers. It has the means. The only direct personal experience I’ve had of such a thing in Britain was when I had the so-called Henfield Writing Fellowship at the University of East Anglia, in the summer term of 1972. It was meant to be a sabbatical from the New Statesman – it turned into a lifetime sabbatical, because while I was away Dick Crossman was sacked by the directors, and one of the first things Tony Howard did when he took over was sack me … So I went freelance. But I enjoyed the UEA experience very much, and got through a lot of writing – a lot of my book-length sequence, New Confessions, was done there. I don’t expect you to have read it – it was published in 1973, and is a sort of ‘I-am-Augustine-of-Hippo’s-alter-ego’ invention, a mixture of verse and prose. Not many people have read it.

I have. And I lent my copy to someone and it never came back so it‘s a distant memory now.

I reckon it sold fewer copies than any of my books. I still stand by it, but it’s very difficult to select from, so there’s nothing from it in my Selected Poems. The UEA ‘creative writing’ thing was of course very much a pioneer effort in this country. The term I was there Malcolm Bradbury was away in Zurich; but I saw a good deal of Angus Wilson, who’d started the creative-writing programme with Malcolm, and he was a life-force. I got some poets to come and read, and they had good audiences: Roy Fuller, Peter Porter, George MacBeth. Larkin came to stay with me one weekend – I had a little two-bedroomed flat on the campus – and I gave a party for him one evening: about twenty people. And I somehow persuaded him to read some poems to us – my God, I wish I’d thought of tape-recording it. He read his poems for about half an hour. Everyone was entranced. Next morning, Philip said to me, in his usual mock-lugubrious way, ‘Anthony, you must have got me drunk last night …’ He always used to say that he never read his poems in public.

The other two experiences I’ve had of this sort of thing have been elsewhere. l’ve mentioned the Japan Foundation Fellowship, in 1985-86. That was a marvellous thing, and it was the first time (maybe the only time) that the Japan Foundation, which is a government-funded but independent body – a bit like the British Council – had given a Fellowship to someone simply to write poetry. I mean, imagine what would happen if it leaked out that a Japanese poet had been given funds by the British Council to come to England for a year and write poems in Japanese … There’d be indignant questions in the House. But no one in Japan seemed to take the smallest exception to my fellowship. I did write a good deal, a great deal in fact – while poor Ann went off to lecture on paragraphing, and Romeo and Juliet, and whatnot, at Tokyo Women’s University. She was given a Visiting Professorship there for the year, and we lived in a tiny flat on the campus, which is one of the few pleasant campuses in Tokyo.

The other time I’ve been involved myself in this sort of thing is the semester I spent at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tennessee, from January to April in 1992. I was so-called ‘Poet in Residence’. (I have a university ID card that says ‘Poet in Residence. Expires May 1992.’) That was a very different experience from UEA, you can imagine. I had just two classes a week: one on ‘Contemporary British Poets’, and the other ‘Creative Writing’. I had a few very bright students, and none of them was terrible, and all of them were pleasant. Mind you, I thought Nashville itself a pretty terrible dump, unless you’re very keen on Country and Western, which I’m not. Half the taxi drivers in Nashville seemed to be failed Country and Western musicians. But Vanderbilt itself is a good, rather old-fashioned university, with an excellent library. I had some nice colleagues – it was Laurence Lerner who put me in for the job: he’s English, of course, or rather South African originally. We’d known one another for years, since the late 1950s, and Larry had a very grand title at Vanderbilt – Mabel Lucy Atwell Chair, or something. And Mark Jarman, a very good youngish American poet who’s hardly known here. I was much happier than Kingsley Amis was at Vanderbilt, in the late 1960s, I think: he tells some terrible stories in his Memoirs about his time there. And I believe him – after all, Elizabeth Jane Howard, his ex-wife, or one of his ex-wives, confirmed the stories to me, and she has no reason to defend old Kingsley. But Ann and I were happy there – and, again, it was good for writing. I think the best thing I wrote was a poem called ‘Philip Larkin in New Orleans’, which started off when we went for a few days to Louisiana for the mid-semester break. A marvellous city – and terrible too. I finished off that poem when I got back to Nashville.

Ian suggested in his Keepers of the Flame that you may have been lumbered as a literary executor with a legal blunder or two in Larkin’s testamentary instructions since they apparently leave ambiguities or indecisions, over what is to be distinguished as biographical material as opposed to poetic and creative. At the time of the publication of Larkin’s Collected you took a bit of stick for your inclusiveness despite one of these instructions. Have you any further reflections to shed on these issues?

Ah, the Larkin business … Well, I suppose it follows on from my mentioning ‘Philip Larkin in New Orleans’. Where do I begin? I think the Larkin will was a bit of a mess: Andrew Motion and I felt it from the start, when we read it soon after Philip’s death. Philip had asked me to be his literary executor, and I said, Well, I’m very honoured but, after all, I’m only eight years younger than you are, so shouldn’t you be thinking of someone younger, who could take over, or run in harness, or whatever? So Andrew was brought in. Larkin’s death was very sudden. I mean, when he asked me, and asked Andrew, to join Monica Jones as literary executors, I didn’t imagine that he would die so soon. And certainly Andrew and I didn’t know what was going to be in the will. As it happened, I was away in Japan for that ’85-86 year on the Japan Foundation Fellowship, when first of all Andrew cabled me in July ’85 about Philip’s collapse, and then Philip seemed to be sort-of getting better (though ‘crawling along the bottom of the tank’), and then he died in the December. It was a shock. But then, so was the will – or a puzzle, anyway. Before I got back to England – which wasn’t until April 1986, I think – Andrew and I, and Philip’s solicitor, and Charles Monteith, Philip’s old chum and publisher – we’d all kept pretty well in touch. We had a meeting, all of us, including Monica, in Hull, in May 1986, when we tried to sort things out. We certainly worked out a schedule. And this was agreed by all five of us – Monica, Terry Wheldon, Charles, Andrew, myself. First, there would be a Collected Poems, edited by me, which would include some uncollected and unpublished poems. Then there would be a Selected Letters, edited also by me – I’d asked Andrew whether he’d want to be co-editor, but he declined. Finally, there would be a Biography, and Monica plumped for Andrew. (I’d quite like to have done that, I felt at the time, with some help from Ann – but after all, Andrew had already published his multiple biography of the Lamberts, and shown he could do the job, and I had no track record, and anyway I was doing the other two jobs … As it turned out, I’m very glad Monica decided on Andrew.) As for the ‘testamentary instructions’, how does one make sense of those ‘repugnant’ clauses? (That was the word used by the QC who gave his Learned Opinion.) I strongly feel that we did the right thing.

Again, there was some fairly hefty opposition to the volume of his letters. They were used as a weapon to detract from the standing of the poems.

Well, I still stand by the Selected Letters – I deplore some of the things that have been said about the book, and Larkin, and myself, and the Estate, and so on and so forth. People who are otherwise sane, or reasonably so, seem to have gone crazy about that book, as if it was a criminal cesspit leaking everywhere. Thank God there’ve been some – indeed, a lot – of saner and more positive reactions: not just the good reviews (by John Carey, bless him, and many others), but also all the letters I had from ordinary readers, who embraced this Larkin letter-writer as a friend. The sanctimoniousness and the priggishness of some of the reviewers and writers of letters to the press – I found it unbelievable.

The current journalistic habit of referring to Larkin as the poet who wrote that line about parents fucking you up must make you as furious as it makes Ian and me when there is so much more to Larkin than that aspect. Do you think the way the letters were selected played into the hands of the journalists in any way?

I selected the letters in a way that – I thought – showed all the umpteen sides of Larkin. The only demurs, or perhaps regrets, I have – well, I realised, too late, that I should indeed have included at least some of the family letters, particularly to his mother. That was an omission I now certainly regret. I was so appalled, initially, by the sheer volume of all those letters to Eva that I funked it. And there’s another argument – that the Selected Letters was published too soon after Philip’s death. That may be a good argument, I now see; but, as I’ve said, when we had the May ’86 meeting, we all agreed on the progression – poems, letters, biography. If it comes to that, you see, people might argue that the biography also came out too soon – but it’s such a delicate, and also a circular argument. When does one tell the truth? What is truth …? Jesting Pilate, and all that.

In a previous interview Michael Hamburger suggested that Larkin’s letters had been drastically edited towards the Kingsley Amis facets of the poet’s character to the detriment of elements closer to the poems. Is there any truth in the impression?

Well, Michael Hamburger is wrong. He may be hanging on to his hoard of Philip’s letters, but the ones I saw from Philip to Michael didn’t seem particularly worth publishing – at least, not when I was reading the tens of thousands of letters I did read. The Kingsley letters, whether you ‘like’ them or not, were obviously a very important part of the whole pattern. And really, you know, there weren’t all that many to Kingsley in the book, when one remembers that there are huge chronological gaps (because Kingsley said he’d lost so many letters), in a friendship that lasted from 1941 until 1985. Some people just recoil from that bizarre, raucous, go-on-you-bugger thing in the Larkin/Amis correspondence. It’ll be interesting to see what people say when Zachary Leader’s edition of the Amis letters appears.

Would you have preserved Larkin’s diaries if it had been in your power to do so? Because of his terrible illness and perhaps his terror of death, Larkin may be excused the confusion caused, but is it fair of any writer or artist to leave his executors with such difficult decisions over the destruction or otherwise of his material?

I think I would have preserved them. The decision didn’t of course face me, because Monica acted on what Philip had told her to do. I never saw the diaries, and I – rightly – played no part in any decision about them.

Are there any plans for a selected volume of Larkin containing just the poems he chose to publish in his life-time?

No. The trouble is that the Marvell Press is dead against anything that involves splitting responsibility, money etc., in any way that doesn’t give The Less Deceived top priority. There was enough of a battle over the Faber/Marvell Collected Poems: I don’t think anyone wants to go over that disputed territory again …

The Waywiser Press

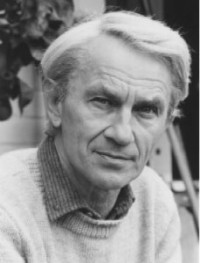

Peter Dale was born in Surrey in 1938, and educated at Strode’s School, Egham, and St Peter’s College, Oxford. For twenty-one years he was head of the English department of Hinchley Wood School, Esher, and concurrently an editor of the poetry quarterly Agenda. Well-known for his Penguin verse-translation of Villon, he has recently published a terza-rima version of Dante’s Divine Comedy and his selected poems, Edge to Edge, both with Anvil Press Poetry Ltd. His Richard Wilbur in Conversation with Peter Dale was published by Between The Lines in 2000. Revised and extended editions of his Poems of François Villon and his Poems of Jules Laforgue appeared from Anvil in 2001. He currently edits a poetry column for Oxford Today.

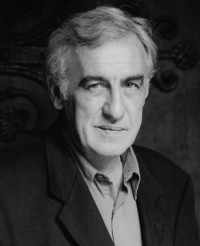

Ian Hamilton was born in 1938, and educated at Darlington Grammar School and Keble College, Oxford. He co-founded and edited The Review (1962-1972), and the New Review (1974-1979), and was for several years poetry and fiction editor for the Times Literary Supplement (1965-1973).

His verse publications include: The Visit (Faber, London,1970), Fifty Poems (Faber, London, 1988), Steps (Cargo Press, 1997), and Sixty Poems (Faber, London, 1999). His prose publications include: A Poetry Chronicle: Essays and Reviews (Faber, London 1973/Barnes and Noble, NY, 1973), The Little Magazines: A Study of Six Editors (Weidenfeld, London, 1976), Robert Lowell: A Biography (Random House, NY, 1982/Faber, London, 1983), In Search of J.D. Salinger (Heinemann, London, 1988/Random House, NY, 1988), Writers in Hollywood, 1915-1951 (Heinemann, London, 1990/Harper, NY, 1990), Keepers of the Flame (Hutchinson, London, 1992), The Faber Book of Soccer (Faber, London, 1992), Gazza Agonistes (Granta/Penguin, London, 1994), Walking Possession (Bloomsbury, London, 1994), A Gift Imprisoned: The Poetic Life of Matthew Arnold (Bloomsbury, London, 1998), The Trouble with Money and Other Essays (Bloomsbury, London, 1998), and Anthony Thwaite in Conversation with Peter Dale and Ian Hamilton (BTL, London, 1999).

Hamilton has also edited a large number of books, amongst them: The Poetry of War, 1939-45 (Alan Ross, London,1965), Alun Lewis: Selected Poetry and Prose (Allen and Unwin, London, 1966), The Modern Poet: Essays from ‘The Review’ (Macdonald, London,1968/Horizon, NY, 1969), Eight Poets (Poetry Book Society, London, 1968), Robert Frost: Selected Poems (Penguin, London, 1973), Poems Since 1900: an Anthology of British and American Verse in the Twentieth Century (with Colin Falck) (Macdonald and Jane’s, London, 1975), Yorkshire and Verse (Secker and Warburg, London, 1984), The ‘New Review’ Anthology (Heinemann, London, 1985), Soho Square (2) (Bloomsbury, London, 1989), the Oxford Companion to 20th Century Poetry (OUP, Oxford, 1996), and the Penguin Book of Twentieth-Century Essays (Penguin, London, 1999).

Between 1984 and 1987 Hamilton presented BBC TV’s Bookmark programme. He now serves on the editorial board of The London Review of Books.

2000

Ian Hamilton, one of the founding editors of Between The Lines, died on December 27, 2001.

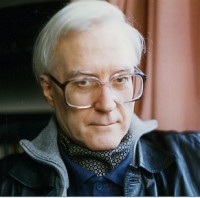

Anthony Thwaite was born in 1930. He spent most of his childhood in Yorkshire until he was evacuated to relations in America during the Second World War. After his stint of national service, some of which was spent in Libya, he went up on a scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford, where he read English. Since that time he has been visiting lecturer in English Literature at Tokyo University, a BBC radio producer, literary editor of The Listener, assistant professor of English at the University of Libya, literary editor of the New Statesman, and between 1973-85 the co-editor of Encounter. He has been a director of a London publisher, working part-time, and combined this with much broadcasting, reviewing and lecturing. He is a literary executor of Larkin’s and edited his Collected Poems and his Selected Letters.

Anthony Thwaite was born in 1930. He spent most of his childhood in Yorkshire until he was evacuated to relations in America during the Second World War. After his stint of national service, some of which was spent in Libya, he went up on a scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford, where he read English. Since that time he has been visiting lecturer in English Literature at Tokyo University, a BBC radio producer, literary editor of The Listener, assistant professor of English at the University of Libya, literary editor of the New Statesman, and between 1973-85 the co-editor of Encounter. He has been a director of a London publisher, working part-time, and combined this with much broadcasting, reviewing and lecturing. He is a literary executor of Larkin’s and edited his Collected Poems and his Selected Letters.Thwaite has written twelve books of verse, and appeared in the first series of Penguin Modern Poets. He has written books of criticism, of travel, and edited selections of Longfellow and R. S. Thomas; he has also published Poetry Today: A Critical Survey 1960-1995. With Geoffrey Bownas, he co-edited The Penguin Book of Japanese Verse. He is a keen traveller, with a passion for archaeology. In 1998, an exhibition of his, ‘A Poet’s Pots’, was put on in The Sainsbury Centre, Norwich.

As poet, his work has developed from the early influence of Larkin to works of very different and larger structure, as in the Letters of Synesius, the series of dramatic monologues in Victorian Voices and meditations based on an imaginative response to his reading of St Augustine of Hippo in New Confessions. Irony and humour were there in the early poems but humour has appeared more often in the making of later poems, some with a satirical edge.

In 1989, he was given an Honorary D.Litt. by the University of Hull, and in 1990 the O.B.E. for services to poetry.

Thwaite lives in south Norfolk with his wife Ann, the biographer and writer of books for children. They have four daughters and eight grand-children.

– Peter Dale, 1999