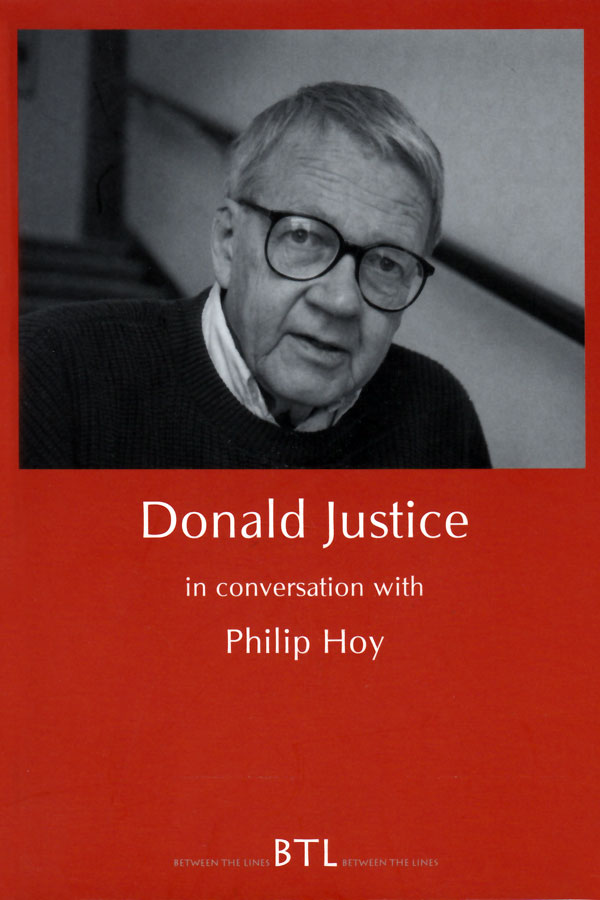

Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy

£9.50

A 130-page volume, containing a lengthy interview, a career sketch, a comprehensive bibliography, a representative selection of quotations from Justice's critics and reviewers, two late poems, four of the poet's woodcuts and extracts from two of his musical compositions.

Out of stock

Between The Lines

For years I have been puzzled that so little has been published about Donald Justice, who seems one of the few truly permanent poets currently writing in English. Now, in one masterful stroke, Philip Hoy covers the whole of the poet’s life and career in this lively, intelligent, and refreshingly candid book-length conversation. This important new book goes a long way to securing Donald Justice’s rightful place in contemporary letters.

– Dana Gioia.

Amongst the teachers you had at Iowa were John Berryman, Robert Lowell and Karl Shapiro, with each of whom you spent a term. I believe you thought Berryman the best teacher?

I did think he was the best, yes, and a large part of how good he was had to do with his very character, however much a few have maligned him. He was full of a kind of fervour or fire, in class and out. In class he was a master of detail and care; he was in love with the whole business of reading and writing and of talking about it, in love with teaching itself, though he had not done much of it. I wouldn’t call him a model exactly, not an example, as with others. His chief difference from the other teachers I had was that he was truly interested in what you were doing. Berryman, Lowell and Shapiro were all terribly self-involved – as what poet is not? – but Berryman had room in his capacious heart to become involved in what you were doing as well – and to care about it.

You seem to have made as much of an impression on him as he did on you. Dana, Snodgrass and others have all written about his excited reaction to your work. Snodgrass recalls a day on which all of you had handed in your assignments. Berryman ‘sat at his desk idly leafing through them, then stopped, stared, and read one of the sonnets to himself. His face aghast, he then turned to the class and said, “It is simply not right that a person should get a poem like that as a classroom assignment!”’ The poem in question was ‘The Wall’, and another of the students who met him for a beer later that week – unnamed, but quoted by Berryman’s biographer, John Haffenden – recalls how Berryman ‘immediately began to read [the sonnet] and … marvelled at [its] opening and the explosive pause in the second line. He was deliriously excited and to this day I can hear him recite it: “The wall surrounding them they never saw; / The angels often.”’ Did Berryman’s reaction to your poem strike you as forcefully as it struck your fellow students?

Everyone seems to have his own version of that story. My version, which I think is the true one, is less dramatic. It’s just that Berryman had phoned me the night before the class meeting to tell me how much he liked the poem. Such enthusiasm was unexpected, such kindness. What happened in class the next day I really can’t recall, except for a faint memory of comments he made regarding some sound effects in that sonnet which I had not been aware of and in fact doubted the effect of, though I’m sure I refrained from saying anything to soften the praise I was getting.

This wasn’t an easy time in Berryman’s life, was it? His wife had left him the previous summer, he’d been out of work and drinking a great deal. The night he’d arrived in Iowa, he’d fallen down the stairs of his boarding house, crashed through a glass door, broken a wrist and sustained some heavy bruising. Were his emotional problems as obvious to his students as his physical problems must have been?

Maybe to others the problems were obvious. Not to me. At least not then. I thought he was living constantly at some kind of emotional peak, like someone on speed, perhaps. But it was, after all, an exciting time for most of us and there were a lot of supercharged guys around. In any case, I tend to remain blind to such matters, and accepting of them.

But Haffenden and Mariani both recount the early morning phone-call Berryman made, begging you to go over to his apartment because he was thinking of killing himself. ‘I got a cab and went right over,’ Haffenden reports you as saying. ‘ When I looked from the hall through his living room door, I saw him sitting on the floor (in bathrobe, I believe) regarding an open case of old-fashioned razors. The sight was too much for me. I felt faint and had to lie down on the sofa. He became immediately all concern and consideration, hurrying down to the bathroom to fetch damp cloths with which to chafe my wrists and so on. Soon I was feeling more myself. To my great relief, so was he.’

Well, of course that incident made me realize how desperate he often was. But John had a capacity for joy as well as suffering, and that’s something discussions of him often ignore. There were calm afternoons drinking beers together in some of the great little taverns of Iowa City. I remember a remark of his from one such afternoon: ‘Thank God I never fell under the influence of Yeats myself.’ At first I thought he must be joking.

And he wasn’t? How very odd. Because he did acknowledge the influence quite freely later on in his life, didn’t he?

I’ve always told the story with Berryman referring to Yeats, but now, with your prompting, it occurs to me that, considering how much worse my memory seems to be getting, it might have been Auden, not Yeats. Berryman’s comment, in either case, still seems pretty startling to me. Perhaps we were in that tavern for longer than I remembered.

What did you make of Lowell’s teaching? Snodgrass thought he was marvellous: ‘However high our expectations,’ he said, ‘no one was disappointed by Lowell’s teaching.’ But Philip Levine, for one, was disappointed. He told Paul Mariani that Lowell played favourites with the students, badly misread a great deal of the poetry under discussion, was fiercely competitive, and wasn’t above overwhelming the class with one of his own poems. ‘In fairness,’ Levine added, ‘he was teetering on the brink of a massive nervous breakdown … Rumours of his hospitalization drifted back to Iowa City, and many of us felt guilty for damning him as a total loss.’ Who was closer to the truth, would you say – those who thought him marvellous or those who thought him a total loss?

I thought Lowell was an excellent teacher. He was someone of great intensity, to whom everything mattered. There was a distance, a decent and probably self-protective distance, but I approve of that, if approval matters. As well, I liked him a lot personally, and he was always very kind to me. All the same, if I don’t remember him quite the way Phil does, it’s nevertheless true that Lowell was more interested in what he himself was writing than in what his students were doing. I remember him reading to us one afternoon an early version of his longish Marie de Medici poem – early in that it was still in his familiar rhyming pentameters – and ending by inviting comments from the class. Of course we thought it was pretty wonderful, but the chorus of praise wasn’t quite unanimous, and Lowell was dismayed. It’s also true that there was a hint of condescension in his regard for student work. This was almost certainly well deserved, of course, but still …

So Berryman was the more endearing teacher?

Berryman went further with us, and we who admired him could not help liking him for a kind of selflessness. But to go back to your original question, my guess is that between those who thought Lowell marvellous and those who thought him a loss – certainly not a total one – we would have had at least a small majority on the marvellous side.

The Waywiser Press

Philip Hoy was born in 1952, and educated at Glastonbury High School in Surrey, and at the Universities of York and Leeds. He has a Ph.D in Philosophy, a subject he taught for many years, in the UK, and, more recently, overseas. Since returning to the UK, in 1996, Hoy has been writing, editing and publishing. His most recent publications include "The Starry Night": Snodgrass’s Van Gogh Reconsidered’ (Agenda, London, 1996), "The Genesis of On Certainty: Some Questions for Professors Anscombe and von Wright’ (Wittgenstein Studien, University of Passau, 1996), the proem and afterword to Peter Dale’s Da Capo (Agenda Editions, London, 1997), "The Will to Power #486/KGW VIII, 1 2[87], 2: A Knot that Won’t Unravel?" (Nietzsche Studien, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1998), W.D. Snodgrass in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1998), Anthony Hecht in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1999, 2001, 2004), Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 2001), "The Interviewer Interviewed: N.S Thompson talks to Philip Hoy, editor of Between The Lines", The Dark Horse, 15, Summer 2003: 40-46. (If you would like to read this article, please follow this link: http://www.waywiser-press.com/imprints/darkhorse.html).

Philip Hoy was born in 1952, and educated at Glastonbury High School in Surrey, and at the Universities of York and Leeds. He has a Ph.D in Philosophy, a subject he taught for many years, in the UK, and, more recently, overseas. Since returning to the UK, in 1996, Hoy has been writing, editing and publishing. His most recent publications include "The Starry Night": Snodgrass’s Van Gogh Reconsidered’ (Agenda, London, 1996), "The Genesis of On Certainty: Some Questions for Professors Anscombe and von Wright’ (Wittgenstein Studien, University of Passau, 1996), the proem and afterword to Peter Dale’s Da Capo (Agenda Editions, London, 1997), "The Will to Power #486/KGW VIII, 1 2[87], 2: A Knot that Won’t Unravel?" (Nietzsche Studien, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1998), W.D. Snodgrass in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1998), Anthony Hecht in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1999, 2001, 2004), Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 2001), "The Interviewer Interviewed: N.S Thompson talks to Philip Hoy, editor of Between The Lines", The Dark Horse, 15, Summer 2003: 40-46. (If you would like to read this article, please follow this link: http://www.waywiser-press.com/imprints/darkhorse.html).Hoy is managing editor of Between The Lines, and executive editor too of The Waywiser Press, the press of which BTL is an imprint. He lives in Surrey.

Donald Justice was born in Miami, Florida, on August 12th 1925, the only child of Vasco and Mary Ethel Justice (née Cook). He attended Allapattah Elementary School, Andrew Jackson High School and the Senior High School in Miami. Then, in the autumn of 1942, he enrolled for a BA in Music at the University of Miami, where he studied for a time with the composer Carl Ruggles. At a certain point, however, Justice decided that he might have more talent as a writer than a composer, and when he took his degree, in 1945, it was not in Music but English.

After a year spent working at odd jobs in New York, Justice entered the University of North Carolina – the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, as it is now known – to study for an MA. There he got to know a number of other people who would go on to make their mark as writers, amongst them the novelist Richard Stern, the poet Edgar Bowers, and the short story writer, Jean Ross, whom he married in 1947, the year he took his MA.

Justice accepted a one-year appointment instructing in English at the University of Miami. Then, with the encouragement of Edgar Bowers, who had gone there the year before, he took up the offer of a place to study for a PhD at Stanford University in California, where he hoped to work under the supervision of Yvor Winters. Unfortunately, the head of department refused to allow this, and, mindful of Justice’s teaching load, insisted that he took only one course per semester, thereby condemning him to very slow progress. Frustrated, Justice left Stanford and went back to Florida, where he resumed the life of an instructor at the University of Miami.

Early in 1951, the Pandanus Press published a small chapbook of Justice’s work, The Old Bachelor and Other Poems. But if the occasion was cause for celebration, it will have been overshadowed by the announcement that the university was letting all of its English instructors go.

Out of work, and unsure what to do next, Justice acted on the advice of friends and applied to study for the PhD in Creative Writing being offered by the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, the oldest institution of its kind in America, founded by Paul Engle in 1937. His application was successful, and in the spring of 1952 Justice joined one of the most distinguished classes ever to pass through the Workshop, his fellow students including Jane Cooper, Henri Coulette, Robert Dana, William Dickey, Philip Levine, W.D. Snodgrass and William Stafford.

In the spring of 1954, just two years after his arrival, Justice obtained his PhD, and was promptly awarded a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship in poetry, which made it possible for him to travel to Europe for the first time. After his return, he spent two years as an assistant professor, one at the University of Missouri at Columbia, the other at Hamline University, St Paul, Minnesota. Then, in 1957, he went back to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he had agreed to take over some of his teaching while Engle was away on leave. This was to have been a temporary appointment, but when Engle returned, he was asked to stay on, and he remained at the Workshop for over ten years.

Justice had been publishing poems in many of the country’s leading journals – amongst them, Poetry, The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Hudson Review, and The Paris Review – and he had been publishing short stories as well – two had been included in O. Henry Prize Stories annual collections – but it wasn’t until 1960, when he was thirty-five years old, that Wesleyan University Press published his first full collection, The Summer Anniversaries. It was very well received: ‘Mr Justice is an accomplished writer,’ wrote Howard Nemerov, ‘whose skill is consistently subordinated to an attitude at once serious and unpretentious. Although his manner is not yet fully disengaged from that of certain modern masters, whom he occasionally echoes, his own way of doing things does in general come through, a voice distinct although very quiet, in poems that are delicate and brave among their nostalgias.’ In competition with books submitted by forty-seven other publishers, The Summer Anniversaries was chosen by the Academy of American Poets as the Lamont Poetry Selection for 1959.

Two small press publications came out in the next few years – A Local Storm in 1963 and Three Poems in 1966 – and so did two edited volumes – The Collected Poems of Weldon Kees in 1960 and Contemporary French Poetry in 1965 – and then, in 1967, the year he left the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Justice’s second full collection was published. Night Light was a very different book from its predecessor, but although it drew some negative reviews – William H. Pritchard summed up his reaction by saying that the book was ‘almost wholly about literature, often not very exciting literature’ – and some of the positive reviews were lazily formulated, Justice will have found the general tenor of the pieces reassuring: ‘This is a book to be grateful for,’ wrote one reviewer, and most of the others were clearly in agreement.

Justice left the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in order to take up an Associate Professorship at Syracuse University in New York. The following year – a year in which he was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship in poetry, and gave the Elliston lectures at the University of Cincinnati – he was appointed full professor. However, Justice remained at Syracuse University for only three years, accepting a one-year appointment at the University of California at Irvine in 1970, and then, in the autumn of 1971, going back for a third time to Iowa.

Two more small press publications came out in the early 1970s – Sixteen Poems in 1970 and From a Notebook in 1972. These were followed by Justice’s third full collection, Departures, which was published in 1973, and was another critical success. Irvin Ehrenpreis described its author as a ‘profoundly gifted’ poet. Richard Howard was no less enthusiastic: ‘[T]his little book [contains] some of the most assured, elegant and heartbreaking … verse in our literature so far.’ Departures was nominated for the 1973 National Book Award.

Justice’s Selected Poems was published in 1979, and its jacket bore a ringing endorsement from Anthony Hecht: ‘Many admiring poets and a few perceptive critics (Paul Fussell, Jr among them) have paid careful, even studious attention to Donald Justice’s poetic skill, which seems able to accomplish anything with an ease that would be almost swagger if it were not so modest of intention. He is, among other things, the supreme heir of Wallace Stevens. His brilliance is never at the service merely of flash and display; it is always subservient to experienced truth, to accuracy, to Justice, the ancient virtue as well as the personal signature. He is one of our finest poets.’ Not all of the reviewers were so well-disposed, however. Calvin Bedient described Justice as ‘an uncertain talent that has not been turned to much account’; Gerald Burns said that the volume ‘reads like a very thin Tennessee Williams’; and Alan Hollinghurst said that the poems, ‘formal but fatigués … create the impression of getting great job satisfaction without actually doing much work.’ Still, those who felt like Bedient, Burns and Hollinghurst were in a small minority, and Justice’s Selected Poems was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1980.

In 1982 Justice returned to the state of his birth to take up a professorship at the University of Florida, Gainsville. Two years later he published Platonic Scripts, which gathered a number of his critical essays and a handful of the interviews he had given since the mid-1960s. Then, in 1987, he published his next full collection, The Sunset Maker, a book whose contents were well described by his old friend Richard Stern in a review for The Chicago Tribune: ‘Poems built so finely out of such intricate emotional music shift in the mind from reading. They are the products, if not the barometer, of an extraordinary temperament coupled with enormous verbal and rhythmic skill. No poem here could have been written by anyone but Donald Justice. This is his world, faintly tropical, faintly melancholy, musical, affectionate, a fixity of evanescence. Beautiful as little else.’

In 1991, by which time he had written the libretto for Edwin London’s opera, The Death of Lincoln, and had co-edited The Collected Poems of Henri Coulette, Justice was awarded the Bollingen Prize, in recognition of a lifetime’s achievement in poetry.

The following year, disenchanted with Florida, and disaffected with the university, Justice retired and moved back to Iowa City. After that, he has published a number of books: A Donald Justice Reader (containing poems, a memoir, short stories and critical essays) appeared in 1992, New and Selected Poems and Banjo Dog in 1995, Oblivion (containing critical essays, appreciations and extracts from notebooks) and Orpheus Hesitated Beside the Black River (an English version of his New and Selected Poems) in 1998. He also co-edited The Comma After Love: Selected Poems of Raeburn Miller (1994) and Joe Bolton’s The Last Nostalgia: Poems 1982-1990 (1999).

In 1997, Justice was elected a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

– Philip Hoy, 2001

In the last few months of his life, Donald Justice was invited to be Poet Laureate of the United States but had to decline because of ill-health. He died on August 6th 2004, and is survived by his wife Jean Ross Justice and their son Nathaniel.

Excerpts

Amongst the teachers you had at Iowa were John Berryman, Robert Lowell and Karl Shapiro, with each of whom you spent a term. I believe you thought Berryman the best teacher?

I did think he was the best, yes, and a large part of how good he was had to do with his very character, however much a few have maligned him. He was full of a kind of fervour or fire, in class and out. In class he was a master of detail and care; he was in love with the whole business of reading and writing and of talking about it, in love with teaching itself, though he had not done much of it. I wouldn’t call him a model exactly, not an example, as with others. His chief difference from the other teachers I had was that he was truly interested in what you were doing. Berryman, Lowell and Shapiro were all terribly self-involved – as what poet is not? – but Berryman had room in his capacious heart to become involved in what you were doing as well – and to care about it.

You seem to have made as much of an impression on him as he did on you. Dana, Snodgrass and others have all written about his excited reaction to your work. Snodgrass recalls a day on which all of you had handed in your assignments. Berryman ‘sat at his desk idly leafing through them, then stopped, stared, and read one of the sonnets to himself. His face aghast, he then turned to the class and said, “It is simply not right that a person should get a poem like that as a classroom assignment!”’ The poem in question was ‘The Wall’, and another of the students who met him for a beer later that week – unnamed, but quoted by Berryman’s biographer, John Haffenden – recalls how Berryman ‘immediately began to read [the sonnet] and … marvelled at [its] opening and the explosive pause in the second line. He was deliriously excited and to this day I can hear him recite it: “The wall surrounding them they never saw; / The angels often.”’ Did Berryman’s reaction to your poem strike you as forcefully as it struck your fellow students?

Everyone seems to have his own version of that story. My version, which I think is the true one, is less dramatic. It’s just that Berryman had phoned me the night before the class meeting to tell me how much he liked the poem. Such enthusiasm was unexpected, such kindness. What happened in class the next day I really can’t recall, except for a faint memory of comments he made regarding some sound effects in that sonnet which I had not been aware of and in fact doubted the effect of, though I’m sure I refrained from saying anything to soften the praise I was getting.

This wasn’t an easy time in Berryman’s life, was it? His wife had left him the previous summer, he’d been out of work and drinking a great deal. The night he’d arrived in Iowa, he’d fallen down the stairs of his boarding house, crashed through a glass door, broken a wrist and sustained some heavy bruising. Were his emotional problems as obvious to his students as his physical problems must have been?

Maybe to others the problems were obvious. Not to me. At least not then. I thought he was living constantly at some kind of emotional peak, like someone on speed, perhaps. But it was, after all, an exciting time for most of us and there were a lot of supercharged guys around. In any case, I tend to remain blind to such matters, and accepting of them.

But Haffenden and Mariani both recount the early morning phone-call Berryman made, begging you to go over to his apartment because he was thinking of killing himself. ‘I got a cab and went right over,’ Haffenden reports you as saying. ‘ When I looked from the hall through his living room door, I saw him sitting on the floor (in bathrobe, I believe) regarding an open case of old-fashioned razors. The sight was too much for me. I felt faint and had to lie down on the sofa. He became immediately all concern and consideration, hurrying down to the bathroom to fetch damp cloths with which to chafe my wrists and so on. Soon I was feeling more myself. To my great relief, so was he.’

Well, of course that incident made me realize how desperate he often was. But John had a capacity for joy as well as suffering, and that’s something discussions of him often ignore. There were calm afternoons drinking beers together in some of the great little taverns of Iowa City. I remember a remark of his from one such afternoon: ‘Thank God I never fell under the influence of Yeats myself.’ At first I thought he must be joking.

And he wasn’t? How very odd. Because he did acknowledge the influence quite freely later on in his life, didn’t he?

I’ve always told the story with Berryman referring to Yeats, but now, with your prompting, it occurs to me that, considering how much worse my memory seems to be getting, it might have been Auden, not Yeats. Berryman’s comment, in either case, still seems pretty startling to me. Perhaps we were in that tavern for longer than I remembered.

What did you make of Lowell’s teaching? Snodgrass thought he was marvellous: ‘However high our expectations,’ he said, ‘no one was disappointed by Lowell’s teaching.’ But Philip Levine, for one, was disappointed. He told Paul Mariani that Lowell played favourites with the students, badly misread a great deal of the poetry under discussion, was fiercely competitive, and wasn’t above overwhelming the class with one of his own poems. ‘In fairness,’ Levine added, ‘he was teetering on the brink of a massive nervous breakdown … Rumours of his hospitalization drifted back to Iowa City, and many of us felt guilty for damning him as a total loss.’ Who was closer to the truth, would you say – those who thought him marvellous or those who thought him a total loss?

I thought Lowell was an excellent teacher. He was someone of great intensity, to whom everything mattered. There was a distance, a decent and probably self-protective distance, but I approve of that, if approval matters. As well, I liked him a lot personally, and he was always very kind to me. All the same, if I don’t remember him quite the way Phil does, it’s nevertheless true that Lowell was more interested in what he himself was writing than in what his students were doing. I remember him reading to us one afternoon an early version of his longish Marie de Medici poem – early in that it was still in his familiar rhyming pentameters – and ending by inviting comments from the class. Of course we thought it was pretty wonderful, but the chorus of praise wasn’t quite unanimous, and Lowell was dismayed. It’s also true that there was a hint of condescension in his regard for student work. This was almost certainly well deserved, of course, but still ...

So Berryman was the more endearing teacher?

Berryman went further with us, and we who admired him could not help liking him for a kind of selflessness. But to go back to your original question, my guess is that between those who thought Lowell marvellous and those who thought him a loss – certainly not a total one – we would have had at least a small majority on the marvellous side.

The Waywiser Press

Interviewer

Philip Hoy was born in 1952, and educated at Glastonbury High School in Surrey, and at the Universities of York and Leeds. He has a Ph.D in Philosophy, a subject he taught for many years, in the UK, and, more recently, overseas. Since returning to the UK, in 1996, Hoy has been writing, editing and publishing. His most recent publications include "The Starry Night": Snodgrass's Van Gogh Reconsidered' (Agenda, London, 1996), "The Genesis of On Certainty: Some Questions for Professors Anscombe and von Wright' (Wittgenstein Studien, University of Passau, 1996), the proem and afterword to Peter Dale's Da Capo (Agenda Editions, London, 1997), "The Will to Power #486/KGW VIII, 1 2[87], 2: A Knot that Won't Unravel?" (Nietzsche Studien, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1998), W.D. Snodgrass in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1998), Anthony Hecht in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1999, 2001, 2004), Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 2001), "The Interviewer Interviewed: N.S Thompson talks to Philip Hoy, editor of Between The Lines", The Dark Horse, 15, Summer 2003: 40-46. (If you would like to read this article, please follow this link: http://www.waywiser-press.com/imprints/darkhorse.html).

Philip Hoy was born in 1952, and educated at Glastonbury High School in Surrey, and at the Universities of York and Leeds. He has a Ph.D in Philosophy, a subject he taught for many years, in the UK, and, more recently, overseas. Since returning to the UK, in 1996, Hoy has been writing, editing and publishing. His most recent publications include "The Starry Night": Snodgrass's Van Gogh Reconsidered' (Agenda, London, 1996), "The Genesis of On Certainty: Some Questions for Professors Anscombe and von Wright' (Wittgenstein Studien, University of Passau, 1996), the proem and afterword to Peter Dale's Da Capo (Agenda Editions, London, 1997), "The Will to Power #486/KGW VIII, 1 2[87], 2: A Knot that Won't Unravel?" (Nietzsche Studien, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1998), W.D. Snodgrass in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1998), Anthony Hecht in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1999, 2001, 2004), Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 2001), "The Interviewer Interviewed: N.S Thompson talks to Philip Hoy, editor of Between The Lines", The Dark Horse, 15, Summer 2003: 40-46. (If you would like to read this article, please follow this link: http://www.waywiser-press.com/imprints/darkhorse.html).

Hoy is managing editor of Between The Lines, and executive editor too of The Waywiser Press, the press of which BTL is an imprint. He lives in Surrey.

Interviewee

Donald Justice was born in Miami, Florida, on August 12th 1925, the only child of Vasco and Mary Ethel Justice (née Cook). He attended Allapattah Elementary School, Andrew Jackson High School and the Senior High School in Miami. Then, in the autumn of 1942, he enrolled for a BA in Music at the University of Miami, where he studied for a time with the composer Carl Ruggles. At a certain point, however, Justice decided that he might have more talent as a writer than a composer, and when he took his degree, in 1945, it was not in Music but English.

After a year spent working at odd jobs in New York, Justice entered the University of North Carolina – the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, as it is now known – to study for an MA. There he got to know a number of other people who would go on to make their mark as writers, amongst them the novelist Richard Stern, the poet Edgar Bowers, and the short story writer, Jean Ross, whom he married in 1947, the year he took his MA.

Justice accepted a one-year appointment instructing in English at the University of Miami. Then, with the encouragement of Edgar Bowers, who had gone there the year before, he took up the offer of a place to study for a PhD at Stanford University in California, where he hoped to work under the supervision of Yvor Winters. Unfortunately, the head of department refused to allow this, and, mindful of Justice’s teaching load, insisted that he took only one course per semester, thereby condemning him to very slow progress. Frustrated, Justice left Stanford and went back to Florida, where he resumed the life of an instructor at the University of Miami.

Early in 1951, the Pandanus Press published a small chapbook of Justice’s work, The Old Bachelor and Other Poems. But if the occasion was cause for celebration, it will have been overshadowed by the announcement that the university was letting all of its English instructors go.

Out of work, and unsure what to do next, Justice acted on the advice of friends and applied to study for the PhD in Creative Writing being offered by the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, the oldest institution of its kind in America, founded by Paul Engle in 1937. His application was successful, and in the spring of 1952 Justice joined one of the most distinguished classes ever to pass through the Workshop, his fellow students including Jane Cooper, Henri Coulette, Robert Dana, William Dickey, Philip Levine, W.D. Snodgrass and William Stafford.

In the spring of 1954, just two years after his arrival, Justice obtained his PhD, and was promptly awarded a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship in poetry, which made it possible for him to travel to Europe for the first time. After his return, he spent two years as an assistant professor, one at the University of Missouri at Columbia, the other at Hamline University, St Paul, Minnesota. Then, in 1957, he went back to the Iowa Writers' Workshop, where he had agreed to take over some of his teaching while Engle was away on leave. This was to have been a temporary appointment, but when Engle returned, he was asked to stay on, and he remained at the Workshop for over ten years.

Justice had been publishing poems in many of the country's leading journals – amongst them, Poetry, The New Yorker, Harper's, The Hudson Review, and The Paris Review – and he had been publishing short stories as well – two had been included in O. Henry Prize Stories annual collections – but it wasn't until 1960, when he was thirty-five years old, that Wesleyan University Press published his first full collection, The Summer Anniversaries. It was very well received: 'Mr Justice is an accomplished writer,' wrote Howard Nemerov, 'whose skill is consistently subordinated to an attitude at once serious and unpretentious. Although his manner is not yet fully disengaged from that of certain modern masters, whom he occasionally echoes, his own way of doing things does in general come through, a voice distinct although very quiet, in poems that are delicate and brave among their nostalgias.' In competition with books submitted by forty-seven other publishers, The Summer Anniversaries was chosen by the Academy of American Poets as the Lamont Poetry Selection for 1959.

Two small press publications came out in the next few years – A Local Storm in 1963 and Three Poems in 1966 – and so did two edited volumes – The Collected Poems of Weldon Kees in 1960 and Contemporary French Poetry in 1965 – and then, in 1967, the year he left the Iowa Writers' Workshop, Justice's second full collection was published. Night Light was a very different book from its predecessor, but although it drew some negative reviews – William H. Pritchard summed up his reaction by saying that the book was 'almost wholly about literature, often not very exciting literature' – and some of the positive reviews were lazily formulated, Justice will have found the general tenor of the pieces reassuring: 'This is a book to be grateful for,' wrote one reviewer, and most of the others were clearly in agreement.

Justice left the Iowa Writers' Workshop in order to take up an Associate Professorship at Syracuse University in New York. The following year – a year in which he was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship in poetry, and gave the Elliston lectures at the University of Cincinnati – he was appointed full professor. However, Justice remained at Syracuse University for only three years, accepting a one-year appointment at the University of California at Irvine in 1970, and then, in the autumn of 1971, going back for a third time to Iowa.

Two more small press publications came out in the early 1970s – Sixteen Poems in 1970 and From a Notebook in 1972. These were followed by Justice's third full collection, Departures, which was published in 1973, and was another critical success. Irvin Ehrenpreis described its author as a 'profoundly gifted' poet. Richard Howard was no less enthusiastic: '[T]his little book [contains] some of the most assured, elegant and heartbreaking ... verse in our literature so far.' Departures was nominated for the 1973 National Book Award.

Justice's Selected Poems was published in 1979, and its jacket bore a ringing endorsement from Anthony Hecht: 'Many admiring poets and a few perceptive critics (Paul Fussell, Jr among them) have paid careful, even studious attention to Donald Justice's poetic skill, which seems able to accomplish anything with an ease that would be almost swagger if it were not so modest of intention. He is, among other things, the supreme heir of Wallace Stevens. His brilliance is never at the service merely of flash and display; it is always subservient to experienced truth, to accuracy, to Justice, the ancient virtue as well as the personal signature. He is one of our finest poets.' Not all of the reviewers were so well-disposed, however. Calvin Bedient described Justice as 'an uncertain talent that has not been turned to much account'; Gerald Burns said that the volume 'reads like a very thin Tennessee Williams'; and Alan Hollinghurst said that the poems, 'formal but fatigués ... create the impression of getting great job satisfaction without actually doing much work.' Still, those who felt like Bedient, Burns and Hollinghurst were in a small minority, and Justice's Selected Poems was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1980.

In 1982 Justice returned to the state of his birth to take up a professorship at the University of Florida, Gainsville. Two years later he published Platonic Scripts, which gathered a number of his critical essays and a handful of the interviews he had given since the mid-1960s. Then, in 1987, he published his next full collection, The Sunset Maker, a book whose contents were well described by his old friend Richard Stern in a review for The Chicago Tribune: 'Poems built so finely out of such intricate emotional music shift in the mind from reading. They are the products, if not the barometer, of an extraordinary temperament coupled with enormous verbal and rhythmic skill. No poem here could have been written by anyone but Donald Justice. This is his world, faintly tropical, faintly melancholy, musical, affectionate, a fixity of evanescence. Beautiful as little else.'

In 1991, by which time he had written the libretto for Edwin London's opera, The Death of Lincoln, and had co-edited The Collected Poems of Henri Coulette, Justice was awarded the Bollingen Prize, in recognition of a lifetime's achievement in poetry.

The following year, disenchanted with Florida, and disaffected with the university, Justice retired and moved back to Iowa City. After that, he has published a number of books: A Donald Justice Reader (containing poems, a memoir, short stories and critical essays) appeared in 1992, New and Selected Poems and Banjo Dog in 1995, Oblivion (containing critical essays, appreciations and extracts from notebooks) and Orpheus Hesitated Beside the Black River (an English version of his New and Selected Poems) in 1998. He also co-edited The Comma After Love: Selected Poems of Raeburn Miller (1994) and Joe Bolton's The Last Nostalgia: Poems 1982-1990 (1999).

In 1997, Justice was elected a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

– Philip Hoy, 2001

In the last few months of his life, Donald Justice was invited to be Poet Laureate of the United States but had to decline because of ill-health. He died on August 6th 2004, and is survived by his wife Jean Ross Justice and their son Nathaniel.