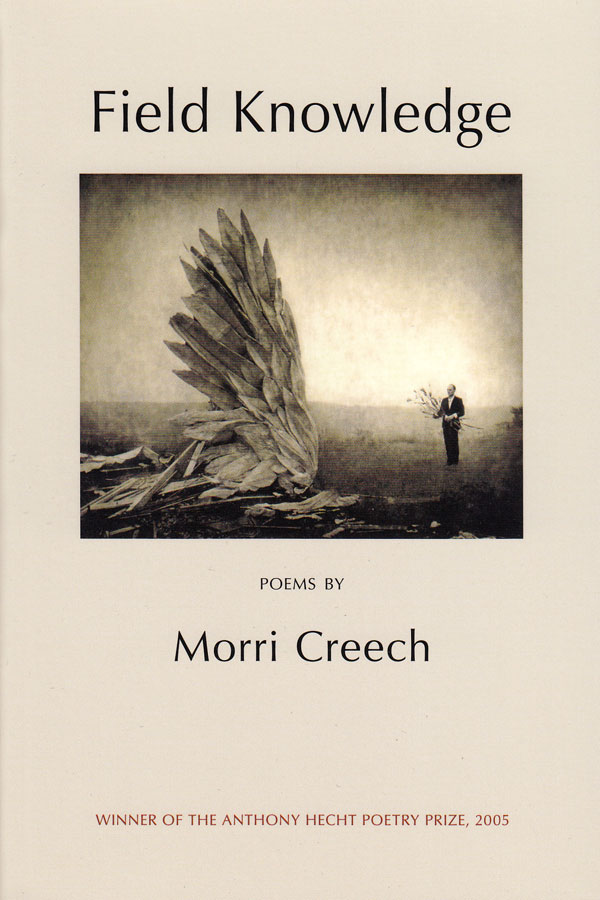

Field Knowledge

£6.99

Winner of the 1st annual Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize

Foreword by the judge, J. D. McClatchyField Knowledge, Morri Creech's second collection, is a series of lyrical meditations on the limits and perils of knowledge, the beauty of experience and its inherent deceptions. Covering a breadth of subjects – from poems about his own family and the connections between local landscape and collective memory, to evocations of Giotto, Newton, and Primo Levi – Creech explores both the familiar world and its hidden mysteries. Many of the poems in this collection share with its predecessor an interest in theological subjects: here are dramatic monologues in the voices of Job and his wife, even an "Elegy for Angels". Other poems evoke both the mysteries and terrors of science, as when Oppenheimer first beholds "the radiant god, shatterer of worlds" in "In the Orchards of Science". Still others examine the cost of experience through a variety of historical and fictional characters, including Marvell's coy mistress, Simone Weil, and Rousseau. Ranging from the humorous to the elegiac, employing both free verse and structured formal stanzas, Creech's lush poems explore the sting of experience while luxuriating in "the honey of knowledge."

Field Knowledge

"Morri Creech’s Field Knowledge has given me more pleasure than any book I have read in years. The judges of the Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize clearly knew their business!" – Frank Kermode

“There are austere poets whose very distance from the world and whose reticent style create a tension that brings the experience described and the poem enacted into a sharper, more heartbreaking focus. And there are luxuriant poets – poets like Keats and Whitman and Hopkins – for whom the world’s bounty and the heart’s bottomless mysteries spill over into lines that almost burst with excess. Morri Creech is a luxuriant, but a canny one …

[H]e has made a book in which a reader can both lose and find himself. Field Knowledge is a rare achievement, and a lasting one.” – J. D. McClatchy, judge of the Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize, 2005 (from the foreword).

"Morri Creech uncovers for us the world as unspeakable enigma … Each thing he holds up to the eye is lit from inside with the fire of its own passing away and its own eternity … These poems transform by a deepest magic." – Li-Young Lee

"Gorgeous as they are, these poems maintain a fine tension between earthly splendors and spiritrual anxieties. As a result, they never slip over the line into extravagance … Morri Creech’s language ‘forges its burnished imprint on the river’ of our own consciousness … [D]azzling." – Susan Ludvigson

"The biblical, as both testament and revelation, is important to this poet the way the mythical is vital to so many others. It is the informing adjective of his imagination and the modifier through which his personal world and the natural world are transformed … His writing fills with light" – Stanley Plumly

Reviews of Field Knowledge

New Criterion , November 2006

"Winner of the first annual Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize, judged by Hecht’s literary executor, J. D. McClatchy, Morri Creech’s Field Knowledge has set the bar high for future aspirants … In a book centered on the pastoral, Creech weaves form into the delicate description of raw, Southern landscapes. He relishes the textured fields of his childhood and the layered histories that the land evokes.

Creech spends much of the book unearthing these stories … but, over time, they seem to take a backseat to the process of recovery itself. In the title poem … Creech lifts, layer by layer, time’s influence on the summer soil: “as if you could prize from weeds and loam one immaculate/ hour, one orient pearl buried at the damp root, and lift it clear/ of the years of corn stalks, furrows, hay rakes freckled with scat – .” The fourth, and last, trochee, in a list that serves to relay the weight of the waste, “freckled” is the perfect word to describe Creech’s memories – sun-worn and spotted.

In the opening poem, “Engine Work: Variations,” Creech remembers his grandfather’s yard; he recalls “stripped engines” and “ripe fruit.” The poem begins with a sense of certainty – “June morning. Sunlight flashes through the pines” – but soon his stanzas deliver doubt: “Or else it’s late – September – .” Creech is uncertain: not only how to repossess the memory of his grandfather, but also whether poetry is capable of such an undertaking …

While Creech’s poetry also explores mythology and science, his personal poems (such as the two quoted here) make Creech’s doubts beautiful, memorable, and poignant. He makes the reader question his own past and the facility with which it can be restored. – Callie Siskel

Booklist

"Aptly enough, Creech’s second collection is the first winner of a prize named after the late Anthony Hecht, who with Richard Wilbur upheld the standard of formal poetry in the generation of American poets that came of age in the 1940s. There are a great many more formalists in or just ahead of Creech’s contingent (he was born in 1970), but perhaps none combines gravity and grace as he does. Those qualities are consciously and consequentially on his mind in the three poems constituting "Some Notes on Grace and Gravity," which consider how Giotto, Leonardo, and Newton, respectively, confirmed the interdependence of grace and gravity. The muralist draws the feet of holy figures to the ground, the painter-scientist turns from rendering saintly flesh to sundering cadavers, and the theoretician unites gravity and grace, mass and motion, materially. If those poems concern the infusion of the sacred into the profane, others mourn modernity’s willful alienation from the sacred, quite often by imaging gods in exile, as in the three poems, placed early, middle, and late in the book, about the travails of Orpheus. Besides such grave pieces, there is much that is witty. Throughout, there is a use of the European poetic tradition that is as gratifying and profound as it is assured. This man’s good." – Ray Olson (Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved)

Antioch Review

"Field Knowledge is intelligent, remarkably dexterous and inventive in its use of form, and – line by line – often dazzling, like "the sprinkler’s lisp and hiss / trailing a veil of diamond through the air." The book is also playful, sometimes very funny – exploring, for example, angels whose heaven involves a trashy casino. Such gifts make Field Knowledge one of the strongest collections this reviewer has read in years." – Benjamin S. Grossman

The Canto of Ulysses

Primo Levi, in his apartment in Turin, reading The Divine Comedy. February, 1987

Drowsing, head propped above the eighth circle,

he feels the present shifting like a keel,

takes his bearings by the toss and swivel

of snow in window light – though still less real,

it seems to him, than that thick Polish snow

which, tumbling in his mind, begins to wheel

like Dante’s leaves or starlings, like the slow

stumble of shades from an open freight car,

or from an open book. All night, the snow

whirls at his window, whiting out the stars.

We sailed now for the stars of that other pole.

Leafing a thumb-worn page, he tries to parse

those lines he once struggled to recall

for a fellow prisoner, who’d hoped to learn

Italian as they scraped rust from the wall

of an emptied petrol tank. The greater horn

began to mutter and move, as a wavering flame

wrestles against the wind and is overworn –

although, oddly enough, the lines sound tame

now there is no one to explain them to.

Nor words to write. His own canticle of pain

is, after all, finished. The past is nothing new.

And the present breaks over him like the dream

of firelight, plush eiderdown, and hot stew

a prisoner will sometimes startle from

who has lost hope of returning to the world,

blowing upon his hands the pluming steam

of breath, in which a few snowflakes are whirled.

Or, nodding above the passage where Ulysses

tells how the second journey ended-hurled

by a fierce squall, till the sea closed over us –

he feels at the moment like that restless king

home from Troy after twenty years, his face

grown old and strange from so much wandering,

who broods all night over the cyclops’ lair

or Circe’s pigs, the shades’ dim gathering,

then falls asleep.

He leans back in his chair.

It all seems now just like it seemed – the snow;

the frozen dead. They whisper on the stair

as if he’d called their shades up from below

to hear the story of Agamemnon slain,

or paced out the long maze of the Inferno

to hear their lamentations fresh again.

Beyond his window: stars, the sleeping town,

the past, whirled like flakes on a windowpane –

the sea closed over us, and the prow went down.

Dreaming, he drops the book without a sound.

The Waywiser Press

Listening to the Earth

after the photograph by Robert Parke Harrison

We’d heard the prophets speak,

knew well their eloquent thunder, the split stone

and urgent whirlwind of their voice and word,

had grown used to the fierce synaptic streaks

of flame, the olive-bearing birds

and withered fields that figured their concern.

But what we’d never heard

was their silence: the wind grown inarticulate

at their retreat from us, the god’s command

hushed in the trees – a voice they’d said had stirred

for our ears that we might understand

what now, plainly, none of us could interpret.

At first we were relieved;

such talk of mystery and consequence

when there was work to do, laundry and errands,

the grain waiting for harvest. So we lived

unhindered for a while, our minds

less cluttered, clearer, fixed in the present tense.

But who would read the hail,

storms and stars, the pale fever of winter sun

or those first harsh winds that flushed the moon’s gold,

swept the corn and mellowed the plums each fall?

Who was there to say what the world

meant? The raven’s flight, bees sweetening carrion,

had little to do with us;

the sparrow’s note was foreign to our ears.

Breezes stirred in the eaves much as before,

it seemed, but kept on saying less and less

about us. On the granary floor

the scattered chaff would not speak to our fears.

It wasn’t the god we missed,

but how a god might sound, those metaphors

and tropes that yoked us to some vast design,

threshing hidden shades up out of the mist,

or lilies that neither toil nor spin,

beneath a sky now strewn with random stars.

And in the plain streets we listened

for those syllables that once conjured the cold,

fathomless swells of Leviathan-haunted seas,

the fabled bush ablaze on hallowed ground,

and snowflakes’ mythic treasuries

transfiguring our ordinary fields.

The Waywiser Press