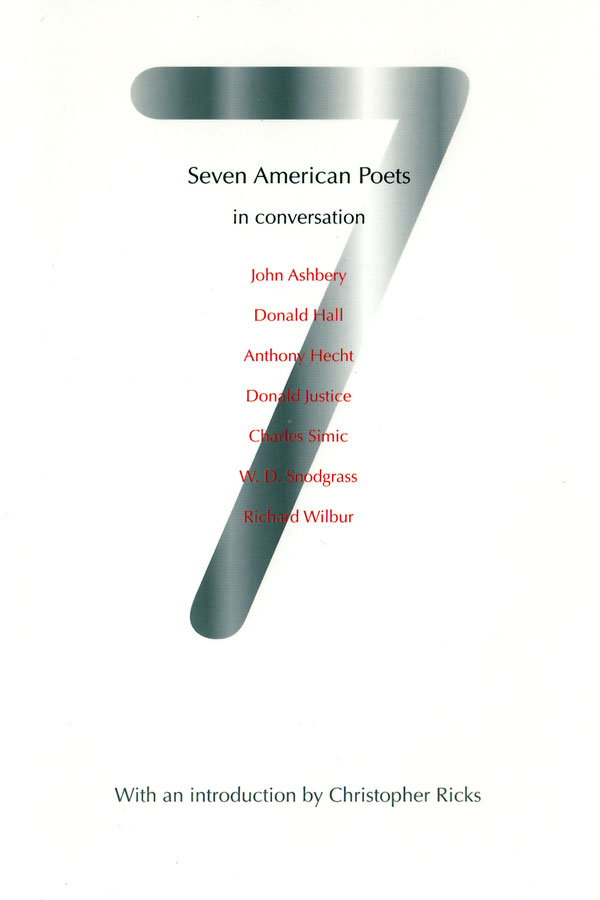

Seven American Poets in Conversation

£10.99

Introduction by Christopher RicksA 480 page volume, gathering together seven of the interviews BTL has conducted with American poets since its founding in 1998. The poets featured are John Ashbery, Donald Hall, Anthony Hecht, Donald Justice, Charles Simic, W. D. Snodgrass, and Richard Wilbur, each of whom talks at length about his work and his life. An informative, entertaining, candid and occasionally surprising panopticon of a book.

Between The Lines

Essential reading for admirers of these poets … vigorous, illuminating and sometimes surprising adjuncts to the work itself.

— Neil Corcoran

These books enrich our contextual understanding of contemporary poetry …

— Patrick Crotty, Times Literary Supplement

A remarkably fine enterprise.

— Dana Gioia

A splendid series.

— X.J. Kennedy

Warmly recommended.

— Glyn Pursglove, Swansea Review

These conversations are skilfully presented and offer sharp new perspectives on their subjects.

— N.S. Thompson, PN Review

Mark Ford was born in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1962. He went to school in London, and attended Oxford and Harvard Universities. He wrote his doctorate at Oxford University on the poetry of John Ashbery, and has published widely on nineteenth- and twentieth-century American writing. From 1991-1993 he was Visiting Lecturer at Kyoto University in Japan. He currently teaches in the English Department at University College London, where he is a Senior Lecturer.

Ford has published two collections of poetry, Landlocked (Chatto & Windus, 1992;1998) and Soft Sift (Faber & Faber, 2001/Harcourt Brace, 2003), and has also written a critical biography of the French poet, playwright and novelist, Raymond Roussel, Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams (Faber & Faber, 2000/Cornell University Press, 2001). A Driftwood Altar, a collection of his essays and reviews, was published by The Waywiser Press in 2005.

He is a regular contributor to the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books and the New York Review of Books, amongst other journals.

Ian Hamilton was born in 1938, and educated at Darlington Grammar School and Keble College, Oxford. He co-founded and edited The Review (1962-1972), and the New Review (1974-1979), and was for several years poetry and fiction editor for the Times Literary Supplement (1965-1973).

His verse publications include: The Visit (Faber, London,1970), Fifty Poems (Faber, London, 1988), Steps (Cargo Press, 1997), and Sixty Poems (Faber, London, 1999). His prose publications include: A Poetry Chronicle: Essays and Reviews (Faber, London 1973/Barnes and Noble, NY, 1973), The Little Magazines: A Study of Six Editors (Weidenfeld, London, 1976), Robert Lowell: A Biography (Random House, NY, 1982/Faber, London, 1983), In Search of J.D. Salinger (Heinemann, London, 1988/Random House, NY, 1988), Writers in Hollywood, 1915-1951 (Heinemann, London, 1990/Harper, NY, 1990), Keepers of the Flame (Hutchinson, London, 1992), The Faber Book of Soccer (Faber, London, 1992), Gazza Agonistes (Granta/Penguin, London, 1994), Walking Possession (Bloomsbury, London, 1994), A Gift Imprisoned: The Poetic Life of Matthew Arnold (Bloomsbury, London, 1998), The Trouble with Money and Other Essays (Bloomsbury, London, 1998), and Anthony Thwaite in Conversation with Peter Dale and Ian Hamilton (BTL, London, 1999).

Hamilton has also edited a large number of books, amongst them: The Poetry of War, 1939-45 (Alan Ross, London,1965), Alun Lewis: Selected Poetry and Prose (Allen and Unwin, London, 1966), The Modern Poet: Essays from ‘The Review’ (Macdonald, London,1968/Horizon, NY, 1969), Eight Poets (Poetry Book Society, London, 1968), Robert Frost: Selected Poems (Penguin, London, 1973), Poems Since 1900: an Anthology of British and American Verse in the Twentieth Century (with Colin Falck) (Macdonald and Jane’s, London, 1975), Yorkshire and Verse (Secker and Warburg, London, 1984), The ‘New Review’ Anthology (Heinemann, London, 1985), Soho Square (2) (Bloomsbury, London, 1989), the Oxford Companion to 20th Century Poetry (OUP, Oxford, 1996), and the Penguin Book of Twentieth-Century Essays (Penguin, London, 1999).

Between 1984 and 1987 Hamilton presented BBC TV’s Bookmark programme. He now serves on the editorial board of The London Review of Books.

2000

Ian Hamilton, one of the founding editors of Between The Lines, died on December 27, 2001.

Philip Hoy was born in 1952, and educated at Glastonbury High School in Surrey, and at the Universities of York and Leeds. He has a Ph.D in Philosophy, a subject he taught for many years, in the UK, and, more recently, overseas. Since returning to the UK, in 1996, Hoy has been writing, editing and publishing. His most recent publications include "The Starry Night": Snodgrass’s Van Gogh Reconsidered’ (Agenda, London, 1996), "The Genesis of On Certainty: Some Questions for Professors Anscombe and von Wright’ (Wittgenstein Studien, University of Passau, 1996), the proem and afterword to Peter Dale’s Da Capo (Agenda Editions, London, 1997), "The Will to Power #486/KGW VIII, 1 2[87], 2: A Knot that Won’t Unravel?" (Nietzsche Studien, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1998), W.D. Snodgrass in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1998), Anthony Hecht in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1999, 2001, 2004), Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 2001), "The Interviewer Interviewed: N.S Thompson talks to Philip Hoy, editor of Between The Lines", The Dark Horse, 15, Summer 2003: 40-46. (If you would like to read this article, please follow this link: http://www.waywiser-press.com/imprints/darkhorse.html).

Philip Hoy was born in 1952, and educated at Glastonbury High School in Surrey, and at the Universities of York and Leeds. He has a Ph.D in Philosophy, a subject he taught for many years, in the UK, and, more recently, overseas. Since returning to the UK, in 1996, Hoy has been writing, editing and publishing. His most recent publications include "The Starry Night": Snodgrass’s Van Gogh Reconsidered’ (Agenda, London, 1996), "The Genesis of On Certainty: Some Questions for Professors Anscombe and von Wright’ (Wittgenstein Studien, University of Passau, 1996), the proem and afterword to Peter Dale’s Da Capo (Agenda Editions, London, 1997), "The Will to Power #486/KGW VIII, 1 2[87], 2: A Knot that Won’t Unravel?" (Nietzsche Studien, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1998), W.D. Snodgrass in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1998), Anthony Hecht in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1999, 2001, 2004), Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 2001), "The Interviewer Interviewed: N.S Thompson talks to Philip Hoy, editor of Between The Lines", The Dark Horse, 15, Summer 2003: 40-46. (If you would like to read this article, please follow this link: http://www.waywiser-press.com/imprints/darkhorse.html).

Hoy is managing editor of Between The Lines, and executive editor too of The Waywiser Press, the press of which BTL is an imprint. He lives in Surrey.

Michael Hulse was born in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire in 1955, and educated locally (1966-1971) and at the University of St Andrews (1973-1977), where he took an MA in German. From the late Seventies until very recently, he lived in Germany, working as a university lecturer, and as an editor, reviewer, translator and publisher.

Michael Hulse was born in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire in 1955, and educated locally (1966-1971) and at the University of St Andrews (1973-1977), where he took an MA in German. From the late Seventies until very recently, he lived in Germany, working as a university lecturer, and as an editor, reviewer, translator and publisher.

Hulse’s poetry collections include Knowing and Forgetting (Secker and Warburg, London, 1981), Propaganda (Secker and Warburg, London 1985), and Eating Strawberries in the Necropolis (Collins Harvill, London, 1991). Empires and Holy Lands: Poems 1976-2000, appeared from Salt Publishing (Cambridge) in 2002.

Amongst the fifty or more books Hulse has translated into English are J.W. Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther (Penguin, London, 1989), Jakob Wassermann’s Caspar Hauser (Penguin, London, 1992), Botho Strauss’s Tumult (Carcanet, Manchester/New York, 1984), and W.G. Sebald’s The Emigrants (Harvill, London/New Directions, New York, 1996), The Rings of Saturn (Harvill, London/New Directions, New York, 1998) and Vertigo (Harvill, London/New Directions, New York, 1999).

Hulse teaches on the Writing Programme at the University of Warwick.

Peter Dale was born in Surrey in 1938, and educated at Strode’s School, Egham, and St Peter’s College, Oxford. For twenty-one years he was head of the English department of Hinchley Wood School, Esher, and concurrently an editor of the poetry quarterly Agenda. Well-known for his Penguin verse-translation of Villon, he has recently published a terza-rima version of Dante’s Divine Comedy and his selected poems, Edge to Edge, both with Anvil Press Poetry Ltd. His Richard Wilbur in Conversation with Peter Dale was published by Between The Lines in 2000. Revised and extended editions of his Poems of François Villon and his Poems of Jules Laforgue appeared from Anvil in 2001. He currently edits a poetry column for Oxford Today.

John Lawrence Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York, on July 28th 1927, the first son of Chester Frederick (a farmer) and Helen Ashbery (a biology teacher). He went to school in Rochester and in his home town of Sodus, and at the age of sixteen was sent as a boarder to Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. After graduating from there, in 1945, he entered Harvard University, where he studied English.

John Lawrence Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York, on July 28th 1927, the first son of Chester Frederick (a farmer) and Helen Ashbery (a biology teacher). He went to school in Rochester and in his home town of Sodus, and at the age of sixteen was sent as a boarder to Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. After graduating from there, in 1945, he entered Harvard University, where he studied English.

Ashbery had been writing poetry since his schooldays, and while at Deerfield had even had two of his poems accepted by the prestigious magazine, Poetry. Two years after he went to college he submitted work to The Harvard Advocate, the recently revived undergraduate magazine, whose editors were Robert Bly, Donald Hall and Kenneth Koch. The poems were quickly published, and just a few months later their author found himself installed as the fourth member of the magazine’s editorial board. According to Hall, he rapidly became the Advocate’s leading light.

Ashbery obtained his BA in 1949, and went to Columbia University to study for his MA. He graduated from there in 1951, and found work in publishing, becoming a copywriter, first for Oxford University Press and then for the McGraw Hill Book Company. Poems of his continued to appear in magazines, amongst them Furioso, Poetry New York and Partisan Review, but as well as pursuing his literary interests, Ashbery was now mixing in New York’s artistic circles, frequenting the galleries, and getting to know the painters. Then, in 1953, thanks to its director, John Myers, the city’s influential Tibor de Nagy Gallery published a slender chapbook of Ashbery’s poems, complete with illustrations by the artist Jane Freilicher. Turandot and Other Poems seems not to have attracted much notice, but Alfred Corn subsequently included its publication in a list of the most important events ‘in the history of twentieth century avant-garde art’.

Three years later, by which time he was in Paris on a Fulbright fellowship, Ashbery’s first full collection was chosen by W.H. Auden for inclusion in Yale University Press’s Younger Poets Series. Reviewing Some Trees for Poetry, Frank O’Hara wrote of Ashbery’s ‘faultless music’ and ‘originality of perception’, and pronounced it ‘the most beautiful first book to appear in America since Harmonium’. Not everyone felt so enthusiastic, however. William Arrowsmith, writing for The Hudson Review, declared that he had ‘no idea most of the time what Mr Ashbery is talking about … beyond the communication of an intolerable vagueness that looks as if it was meant for precision,’ and added, for good measure: ‘What does come through is an impression of an impossibly fractured brittle world, depersonalized and discontinuous, whose characteristic emotional gesture is an effete and cerebral whimsy.’

Ashbery’s period as a Fulbright fellow came to an end in 1957, but life in Paris had been so much to his liking that, after another year in the US – a year in which he took graduate classes at New York University and worked as an instructor in elementary French – he returned, avowedly to pursue research for a doctoral dissertation on the writer Raymond Roussel. He was to remain in France for several years, supporting himself by writing for a number of different journals. He had started to review for the magazine ArtNews during his year in New York, and continued with this once back in Paris. Then, in 1960, he became art critic for the New York Herald Tribune (international edition), and, in 1961, art critic for Art International as well. Nor were these his only such commitments. In the same year that he started writing for the New York Herald Tribune, he joined with Kenneth Koch, Harry Mathews, and James Schuyler and founded the literary magazine, Locus Solus. That folded in 1962, but the following year he got together with Anne Dunn, Rodrigo Moynihan and Sonia Orwell, and founded Art and Literature, a quarterly review he worked on until he went back to living in the US, in 1966.

When not writing reviews, or engaged in editorial work, Ashbery still found time to write poetry. It was poetry of a very different kind to that he had published in Some Trees, however, and readers familiar with the first book will have been altogether unprepared for the ‘violently experimental’ character of the second (unless they had been keeping an eye on Big Table and Locus Solus, the magazines in which some of these poems first appeared). Reactions to The Tennis Court Oath were generally hostile. James Schevill told readers of the Saturday Review: ‘The trouble with Ashbery’s work is that he is influenced by modern painting to the point where he tries to apply words to the page as if they were abstract, emotional colors and shapes … Consequently, his work loses coherence … There is little substance to the poems in this book.’ And Mona Van Duyn told readers of Poetry: ‘If a state of continuous exasperation, a continuous frustration of expectation, a continuous titillation of the imagination are sufficient response to a series of thirty-one poems, then these have been successful. But to be satisfied with such a response I must change my notion of poetry.’ Even so devoted an admirer of Ashbery as Harold Bloom thought the book a ‘fearful disaster’ and confessed to being baffled at how its author could have ‘collapse[d] into such a bog’ just six years after Some Trees.

Ashbery has said that when he was working on the poems that went into The Tennis Court Oath he was ‘taking language apart so I could look at the pieces that made it up’, and that after he’d done this he was intent on ‘putting [the pieces] back together again’. Rivers and Mountains, published in the year that he settled back in the US, was the first of his books to follow, and marked what several of his critics regard as his real arrival as a poet, with poems such as “These Lacustrine Cities”, “Clepsydra” and “The Skaters” all demonstrating for the first time what one of them has called the ‘astonishing range and flexibility of Ashbery’s voice’. The volume was nominated for the National Book Award.

Ashbery had gone back to the US after being offered the job of executive editor of ArtNews. Four years later, in 1969, the Black Sparrow Press published his long poem “Fragment”, with illustrations by the painter Alex Katz. Writing about this seven years on, Bloom declared that it was, for him, Ashbery’s ‘finest work’. By then, it should be noted, the poem had plenty of rivals, since The Double Dream of Spring (which included “Fragment”) had appeared in 1970, Three Poems had appeared in 1972, and The Vermont Notebook and Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror had appeared in 1975. All of these books had won Ashbery admiring notices, and Three Poems had also secured him the Modern Poetry Association’s Frank O’Hara Prize, but it was Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror that proved to be the breakthrough, carrying off all three of America’s most important literary prizes – the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. John Malcolm Brinnin’s notice for the New York Times Book Review can be taken as representative: ‘[A] collection of poems of breathtaking freshness and adventure in which dazzling orchestrations of language open up whole areas of consciousness no other American poet has even begun to explore …‘

ArtNews was sold in 1972, and Ashbery had to find himself another job. A Guggenheim Fellowship sustained him for some months, but then, in 1974, he took up the offer of a teaching post at Brooklyn College – a part of the City University of New York – where he co-directed the MFA program in creative writing. Though he has confessed to not liking teaching very much, he has been doing it ever since (with one extended break between 1985 and 1990, made possible by the award of a MacArthur Foundation fellowship). He left Brooklyn College in 1990, was Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard between 1989 and 1990, and from then until now has been Charles P. Stevenson, Jr. Professor of Languages and Literature at Bard College at Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Just as Ashbery’s art reviewing and editorial work seemed not to affect his creative output during the Sixties and early Seventies, so his teaching work seems not to have affected it during the decades since. In fact, he has been remarkably prolific, averaging a new collection once every eighteen months. Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror was followed by: Houseboat Days (1977), As We Know (1979), Shadow Train (1981), A Wave (1984), April Galleons (1987), Flow Chart (1991), Hotel Lautréamont (1992), And the Stars Were Shining (1994), Can You Hear, Bird (1995), Wakefulness (1998), Girls on the Run (1999), Your Name Here (2000), As Umbrellas Follow Rain (2001) and Chinese Whispers (2002) (to mention only his book-length collections). He has also published Three Plays (1978), Reported Sightings (a selection of his art reviews) (1989) and Other Traditions (revised versions of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures he gave in 1989 and 1990).

This large body of work has won Ashbery numerous admirers, amongst them some of today’s most prominent critics. It has also won him numerous honours, awards and prizes, a partial list of which would include (apart from those already mentioned) two Ingram Merrill Foundation grants (1962, 1972), Poetry magazine’s Harriet Monroe Poetry Award (1963) and Union League Civic and Arts Foundation Prize (1966), two Guggenheim fellowships (1967, 1973), two National Endowment for the Arts publication awards (1969, 1970), the Poetry Society of America’s Shelley Memorial Award (1973), Poetry magazine’s Levinson Prize (1977), a National Endowment for the Arts Composer/Librettist grant (with Elliott Carter) (1978), a Rockefeller Foundation grant for playwriting (1979-1980), the English Speaking Union Award (1979), membership of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (1980), fellowship of the Academy of American Poets (1982), the New York City Mayor’s Award of Honour for Arts and Culture, Bard College’s Charles Flint Kellogg Award in Art and Letters, membership of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1983), American Poetry Review’s Jerome J. Shestack Poetry Award (1983, 1995), Nation magazine’s Lenore Marshall Award, the Bollingen Prize, Timothy Dwight College/Yale University’s Wallace Stevens fellowship (1985), the MLA Common Wealth Award in Literature (1986), the American Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award (1987), Chancellorship of the Academy of American Poets (1988-1989), Brandeis University’s Creative Arts Award in Poetry (Medal) (1989), the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts (Munich)’s Horst Bienek Prize for Poetry (1991), Poetry magazine’s Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Academia Nazionale dei Lincei (Rome)’s Antonio Feltrinelli International Prize for Poetry (1992), the French Ministry of Education and Culture (Paris)’s Chevalier de L’Ordre des Arts et Lettres (1993), the Poetry Society of America’s Robert Frost Medal (1995), the Grand Prix des Biennales Internationales de Poésie (Brussels), the Silver Medal of the City of Paris (1996), the American Academy of Arts and Letters’s Gold Medal for Poetry (1997), Boston Review of Books’s Bingham Poetry Prize (1998), the State of New York/New York State Writers Institute’s Walt Whitman Citation of Merit (2000), Columbia County (New York) Council on the Arts Special Citation for Literature, the Academy of American Poets’s Wallace Stevens Award, Harvard University’s Signet Society Medal for Achievement in the Arts (2001), the New York State Poet Laureateship (2001-2002), and France’s Officier de la Légion d’Honneur (2002).

Ashbery lives in the Chelsea district of New York City and in Hudson, New York.

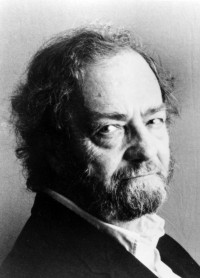

Donald Hall was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1928, the only child of Donald Andrew Hall (a businessman) and his wife Lucy (née Wells). He was educated at Phillips Exeter, New Hampshire, and at the Universities of Harvard, Oxford and Stanford.

Hall began writing even before reaching his teens, beginning with poems and short stories, and then moving on to novels and dramatic verse. He recalls the powerful influence on his youthful imagination of Edgar Allan Poe: ‘I wanted to be mad, addicted, obsessed, haunted and cursed. I wanted to have deep eyes that burned like coals – profoundly melancholic, profoundly attractive.’

Hall continued to write throughout his prep school years at Exeter Phillips, and, while still only sixteen years old, attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, where he made his first acquaintance with the poet Robert Frost. That same year, he published his first work.

While an undergraduate at Harvard, Hall served on the editorial board of the Harvard Advocate, and got to know a number of people who, like him, were poised for significant things in the literary world, amongst them John Ashbery, Robert Bly, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, and Adrienne Rich.

After leaving Harvard, Hall went to Oxford for two years, to study for the B.Litt. While there, he found time not only to edit The Fantasy Poets – in which capacity, he published first volumes by two more people who were set to make their mark on the literary world, Thom Gunn and Geoffrey Hill – but also to maintain four other valuable positions, as editor of the Oxford Poetry Society’s journal, as literary editor of Isis, as editor of New Poems, and as poetry editor of the Paris Review. At the end of his first Oxford year, Hall also won the university’s prestigious Newdigate Prize, awarded for his long poem, ‘Exile’.

On returning to the United States, Hall went to Stanford, where he spent one year as a Creative Writing Fellow, studying under the poet-critic, Yvor Winters. In Their Ancient Glittering Eyes – a book which merits comparison with Hazlitt’s ‘My First Acquaintance with Poets’ – he recalls Winters greeting him with the words, ‘You come from Harvard, where they think I’m lower than the carpet,’ adding, after a pause, ‘Do you realize that you will be ridiculed, the rest of your life, for having studied a year with me?’

Following his year at Stanford, Hall went back to Harvard, where he spent three years in the Society of Fellows. During that time, he put together his first book, Exiles and Marriages, and with Robert Pack and Louis Simpson also edited an anthology which was to make a significant impression on both sides of the Atlantic, The New Poets of England and America.

Hall was appointed to the faculty in the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in 1957, and apart from two one-year breaks in England continued to teach there until 1975, when, after three years of marriage to his second wife, the poet Jane Kenyon, he abandoned the security of his academic career, and went with her to live in rural New Hampshire, on the farm settled by his maternal great-grandfather over one hundred years earlier.

Ever since that time, Hall has supported himself by writing. When not working on poems, he has turned his hand to reviews, criticism, textbooks, sports journalism, memoirs, biographies, children’s stories, and plays. He has also devoted a lot of time to editing: between 1983 and 1996 he oversaw publication of more than sixty titles for the University of Michigan Press alone. At one time, Hall estimated that he was publishing a minimum of one item per week, and four books a year.

In 1989, when Hall was sixty-one, it was discovered that he had colon cancer. Surgery followed, but by 1992 the cancer had metastasized to his liver. After another operation, and chemotherapy, he went into remission, though he was told that he only had a one-in-three chance of surviving the next five years. Then, early in 1994, when the thought uppermost in his and his wife’s minds was that his own cancer might re-appear, it was discovered that she had leukaemia. Her illness, her death fifteen months later, and Hall’s struggle to come to terms with these things, were the subject of his most recent book, Without.

Winters’s prediction that Hall would never live down the year he spent studying in California could hardly have been more wrong. Forty-five years after leaving Stanford, Hall is one of America’s leading men of letters, the author of no less than fourteen books of poetry and twenty-two books of prose. He was for five years Poet Laureate of his home state, New Hampshire (1984-89), and can list among the many other honours and awards to have come his way: the Lamont Poetry Prize (1955), the Edna St Vincent Millay Award (1956), two Guggenheim Fellowships (1963-64, 1972-73), inclusion on the Horn Book Honour List (1986), the Sarah Josepha Hale Award (1983), the Lenore Marshall Award (1987), the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry (1988), the NBCC Award (1989), the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in poetry (1989), and the Frost Medal (1990). He has been nominated for the National Book Award on three separate occasions (1956, 1979 and 1993).

– Philip Hoy, 2000

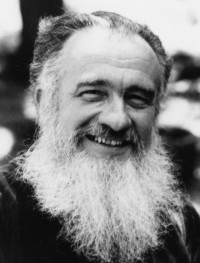

Anthony Hecht was born in New York City in 1923, the first son of Melvyn Hahlo Hecht and Dorothea Hecht (née Holzman). His brother Roger, who would also become a poet, was born two and a half years later.

Anthony Hecht was born in New York City in 1923, the first son of Melvyn Hahlo Hecht and Dorothea Hecht (née Holzman). His brother Roger, who would also become a poet, was born two and a half years later.

Hecht was educated at three of New York City’s schools, and then, in 1940, enrolled as an undergraduate at Bard College, an experimental adjunct of Columbia University, situated at Annandale-on-Hudson. It was at Bard, while still a freshman, that he made up his mind to become a poet, having been introduced to the work of Wallace Stevens, T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, Dylan Thomas and others by an inspiring teacher called Lawrence Leighton.

WWII obliged Hecht to give up his studies before graduating. At first, it looked as though he would be assigned to do intelligence work, but the special training programme he was inducted into was cancelled at the last minute, with the result that Hecht found himself en route to Europe, and some of the bloodiest fighting of the war. Any reader curious to know why the subject of cruelty recurs so frequently in Hecht’s work need look no further than this period in his life for the explanation.

After the war was over, Hecht – whose B.A. had been awarded in absentia – took advantage of the G.I. Bill of Rights and went to Kenyon College in Ohio, where he resumed his studies, this time under the supervision of John Crowe Ransom, one of the most gifted men of letters of the day. It was Ransom who gave Hecht his first English classes to teach, thereby setting him on the path to a long and distinguished career as a professor; and it was Ransom, too, as editor of the Kenyon Review, who published some of Hecht’s earliest poems, thereby setting him on the path to an even longer and still more distinguished career as a poet.

In the fifty years since his days as a student at Kenyon, Hecht has published seventeen books of poetry, three books of criticism, and a large number of essays, reviews, discussion pieces, forewords, prefaces and introductions. He has also done acclaimed work as a translator and editor.

Hecht’s endeavours have been rewarded with a string of prestigious prizes and awards, amongst them: the Prix de Rome (1951), the Brandeis University Creative Arts Award (1965), the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the Russell Loines Award (1968), the Bollingen Prize in Poetry (1983), the Librex-Guggenheim Eugenio Montale Award (1984), the Harriet Monroe Award (1987), the Ruth B. Lilly Poetry Prize (1988), the Tanning Prize (1997), the Corrington Award (1997), and the Poetry Society of America’s Frost Medal (2000).

Other honours to come Hecht’s way included two Guggenheim Fellowships (1954 and 1959), The Hudson Review Fellowship (1958), two Ford Foundation Fellowships (1960 and 1968), a Rockefeller Fellowship (1967), a Fulbright Professorship in Brazil (1969), an Honorary Fellowship with the Academy of American Poets (1969), Membership of the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1979), Chancellorship (1971) and Chancellorship Emeritus (1995) of the Academy of American Poets, and Trusteeship of the American Academy in Rome (1983). He was also Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. (1982-1984).

As well as the B.A. he was awarded by Bard College in 1944, and the M.A. he was awarded by Columbia University in 1950, Hecht has received honorary doctorates from Bard College (1970), Georgetown University (1981), Towson State University, Maryland (1983) and the University of Rochester (1987).

Hecht has three sons, two by his first marriage, to Patricia Harris, which ended in divorce in 1961, and one by his second, to Helen D’Alessandro – the author of several renowned cookery books, and a successful interior designer – with whom he lives in Washington D.C.

– Philip Hoy, 1999, revised 2001

Anthony Hecht died at his home in Washington DC on October 20th 2004

Donald Justice was born in Miami, Florida, on August 12th 1925, the only child of Vasco and Mary Ethel Justice (née Cook). He attended Allapattah Elementary School, Andrew Jackson High School and the Senior High School in Miami. Then, in the autumn of 1942, he enrolled for a BA in Music at the University of Miami, where he studied for a time with the composer Carl Ruggles. At a certain point, however, Justice decided that he might have more talent as a writer than a composer, and when he took his degree, in 1945, it was not in Music but English.

After a year spent working at odd jobs in New York, Justice entered the University of North Carolina – the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, as it is now known – to study for an MA. There he got to know a number of other people who would go on to make their mark as writers, amongst them the novelist Richard Stern, the poet Edgar Bowers, and the short story writer, Jean Ross, whom he married in 1947, the year he took his MA.

Justice accepted a one-year appointment instructing in English at the University of Miami. Then, with the encouragement of Edgar Bowers, who had gone there the year before, he took up the offer of a place to study for a PhD at Stanford University in California, where he hoped to work under the supervision of Yvor Winters. Unfortunately, the head of department refused to allow this, and, mindful of Justice’s teaching load, insisted that he took only one course per semester, thereby condemning him to very slow progress. Frustrated, Justice left Stanford and went back to Florida, where he resumed the life of an instructor at the University of Miami.

Early in 1951, the Pandanus Press published a small chapbook of Justice’s work, The Old Bachelor and Other Poems. But if the occasion was cause for celebration, it will have been overshadowed by the announcement that the university was letting all of its English instructors go.

Out of work, and unsure what to do next, Justice acted on the advice of friends and applied to study for the PhD in Creative Writing being offered by the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, the oldest institution of its kind in America, founded by Paul Engle in 1937. His application was successful, and in the spring of 1952 Justice joined one of the most distinguished classes ever to pass through the Workshop, his fellow students including Jane Cooper, Henri Coulette, Robert Dana, William Dickey, Philip Levine, W.D. Snodgrass and William Stafford.

In the spring of 1954, just two years after his arrival, Justice obtained his PhD, and was promptly awarded a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship in poetry, which made it possible for him to travel to Europe for the first time. After his return, he spent two years as an assistant professor, one at the University of Missouri at Columbia, the other at Hamline University, St Paul, Minnesota. Then, in 1957, he went back to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he had agreed to take over some of his teaching while Engle was away on leave. This was to have been a temporary appointment, but when Engle returned, he was asked to stay on, and he remained at the Workshop for over ten years.

Justice had been publishing poems in many of the country’s leading journals – amongst them, Poetry, The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Hudson Review, and The Paris Review – and he had been publishing short stories as well – two had been included in O. Henry Prize Stories annual collections – but it wasn’t until 1960, when he was thirty-five years old, that Wesleyan University Press published his first full collection, The Summer Anniversaries. It was very well received: ‘Mr Justice is an accomplished writer,’ wrote Howard Nemerov, ‘whose skill is consistently subordinated to an attitude at once serious and unpretentious. Although his manner is not yet fully disengaged from that of certain modern masters, whom he occasionally echoes, his own way of doing things does in general come through, a voice distinct although very quiet, in poems that are delicate and brave among their nostalgias.’ In competition with books submitted by forty-seven other publishers, The Summer Anniversaries was chosen by the Academy of American Poets as the Lamont Poetry Selection for 1959.

Two small press publications came out in the next few years – A Local Storm in 1963 and Three Poems in 1966 – and so did two edited volumes – The Collected Poems of Weldon Kees in 1960 and Contemporary French Poetry in 1965 – and then, in 1967, the year he left the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Justice’s second full collection was published. Night Light was a very different book from its predecessor, but although it drew some negative reviews – William H. Pritchard summed up his reaction by saying that the book was ‘almost wholly about literature, often not very exciting literature’ – and some of the positive reviews were lazily formulated, Justice will have found the general tenor of the pieces reassuring: ‘This is a book to be grateful for,’ wrote one reviewer, and most of the others were clearly in agreement.

Justice left the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in order to take up an Associate Professorship at Syracuse University in New York. The following year – a year in which he was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship in poetry, and gave the Elliston lectures at the University of Cincinnati – he was appointed full professor. However, Justice remained at Syracuse University for only three years, accepting a one-year appointment at the University of California at Irvine in 1970, and then, in the autumn of 1971, going back for a third time to Iowa.

Two more small press publications came out in the early 1970s – Sixteen Poems in 1970 and From a Notebook in 1972. These were followed by Justice’s third full collection, Departures, which was published in 1973, and was another critical success. Irvin Ehrenpreis described its author as a ‘profoundly gifted’ poet. Richard Howard was no less enthusiastic: ‘[T]his little book [contains] some of the most assured, elegant and heartbreaking … verse in our literature so far.’ Departures was nominated for the 1973 National Book Award.

Justice’s Selected Poems was published in 1979, and its jacket bore a ringing endorsement from Anthony Hecht: ‘Many admiring poets and a few perceptive critics (Paul Fussell, Jr among them) have paid careful, even studious attention to Donald Justice’s poetic skill, which seems able to accomplish anything with an ease that would be almost swagger if it were not so modest of intention. He is, among other things, the supreme heir of Wallace Stevens. His brilliance is never at the service merely of flash and display; it is always subservient to experienced truth, to accuracy, to Justice, the ancient virtue as well as the personal signature. He is one of our finest poets.’ Not all of the reviewers were so well-disposed, however. Calvin Bedient described Justice as ‘an uncertain talent that has not been turned to much account’; Gerald Burns said that the volume ‘reads like a very thin Tennessee Williams’; and Alan Hollinghurst said that the poems, ‘formal but fatigués … create the impression of getting great job satisfaction without actually doing much work.’ Still, those who felt like Bedient, Burns and Hollinghurst were in a small minority, and Justice’s Selected Poems was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1980.

In 1982 Justice returned to the state of his birth to take up a professorship at the University of Florida, Gainsville. Two years later he published Platonic Scripts, which gathered a number of his critical essays and a handful of the interviews he had given since the mid-1960s. Then, in 1987, he published his next full collection, The Sunset Maker, a book whose contents were well described by his old friend Richard Stern in a review for The Chicago Tribune: ‘Poems built so finely out of such intricate emotional music shift in the mind from reading. They are the products, if not the barometer, of an extraordinary temperament coupled with enormous verbal and rhythmic skill. No poem here could have been written by anyone but Donald Justice. This is his world, faintly tropical, faintly melancholy, musical, affectionate, a fixity of evanescence. Beautiful as little else.’

In 1991, by which time he had written the libretto for Edwin London’s opera, The Death of Lincoln, and had co-edited The Collected Poems of Henri Coulette, Justice was awarded the Bollingen Prize, in recognition of a lifetime’s achievement in poetry.

The following year, disenchanted with Florida, and disaffected with the university, Justice retired and moved back to Iowa City. After that, he has published a number of books: A Donald Justice Reader (containing poems, a memoir, short stories and critical essays) appeared in 1992, New and Selected Poems and Banjo Dog in 1995, Oblivion (containing critical essays, appreciations and extracts from notebooks) and Orpheus Hesitated Beside the Black River (an English version of his New and Selected Poems) in 1998. He also co-edited The Comma After Love: Selected Poems of Raeburn Miller (1994) and Joe Bolton’s The Last Nostalgia: Poems 1982-1990 (1999).

In 1997, Justice was elected a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

– Philip Hoy, 2001

In the last few months of his life, Donald Justice was invited to be Poet Laureate of the United States but had to decline because of ill-health. He died on August 6th 2004, and is survived by his wife Jean Ross Justice and their son Nathaniel.

Charles Simic was born in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, on May 9th 1938, the first son of George and Helen (Matijevic) Simic.

As a boy, Simic received what he quotes Jan Kott as calling “a typical East European education” – an education, that’s to say, in which “Hitler and Stalin taught us the basics.” What the basics involved is well described in the poet’s recently published memoir, A Fly in the Soup, where, amongst other things, he tells us that “[b]y the time my brother was born, and he and my mother had come home from the clinic, I was in the business of selling gunpowder. Many of us kids had stashes of ammunition, which we collected during the street fighting.”

Towards the end of the war, Simic’s father fled the country, and it was to be ten years before the family would see him again. He had made his way to America, where pre-war employment by an American company (he was an engineer) had given him numerous contacts. However, his wife and children were unable to follow until 1954, the Communist authorities having denied them a passport until 1953, and the US immigration authorities having taken another year or so to process their visa application.

After a year in New York, the family moved to Chicago, where Simic attended Oak Park High School, an earlier alumnus of which had been Ernest Hemingway. He graduated in 1956, but instead of going to college, like most of his peers – his parents had very little in the way of savings, but in any case seem not to have given any thought to the possibility – he found work, first as an office boy, and later as a proof-reader, at the Chicago Sun Times.

It was during this period that Simic started to write poetry. His poetic enthusiasms were various – one month a disciple of Hart Crane, the next a devotee of Walt Whitman – yet this was no mere dalliance: “I’d work at it all night, go to work half-asleep, and then drag myself to night classes.”

In 1958, Simic left Chicago and went back to New York. There he continued to work by day – as parcel-packer, shirt salesman, house painter, book-seller, payroll clerk – and to study by night. He also continued to write, and after a year or more saw his first poems in print, in the Winter 1959 issue of the Chicago Review.

Drafted into the army in 1961, Simic spent most of his two years’ service in Germany and France, working as a military policeman. From a literary historian’s point of view, probably the most noteworthy thing about Simic’s time in the army is that it led him to a radical reappraisal of the sort of poetry he’d been writing. Indeed, so radical was the reappraisal that he ended up destroying everything he’d written, later describing it as “no more than literary vomit”.

After discharge from the army, Simic returned to the life he’d been leading in New York. In 1964, he married Helen Dubin, a fashion designer, and in 1967 he obtained his BA from New York University. A year later his first collection of poems was released by the San Francisco publisher, Kayak. The book was reviewed at some length by William Matthews, who, although he had plenty of criticisms to make, recognized the young poet’s potential: “I found What the Grass Says exciting … What I like in Simic’s poems … is his seriousness … [and] I am impatient to read more …”

In 1966, Simic went to work as an editorial assistant for the photography magazine, Aperture, a job he held until 1969, the year of his second collection, Somewhere Among Us a Stone Is Taking Notes, also published by Kayak. Diane Wakoski’s review of this book opened with the memorable words: “I have not yet decided whether Charles Simic is America’s greatest living Surrealist poet, a children’s writer, a religious writer, or simple-minded.” In fact, and as the rest of her review made clear, Wakoski was a lot closer to thinking Simic the country’s greatest living Surrealist than to thinking him simple-minded. Simic was just thirty-one, but was already gathering a following.

The year after Somewhere Among Us a Stone Is Taking Notes was published, Simic was offered a teaching position in California State College, Hayward, and he remained there until 1973, when he was offered an associate professorship at the University of New Hampshire. He has remained at UNH to this day, though long since promoted to the position of full professor.

In the thirty-six years since his first collection appeared, Simic has published more than sixty books, amongst them Charon’s Cosmology (1977), which was nominated for a National Book Award, Classic Ballroom Dances (1980), which won the University of Chicago’s Harriet Monroe Award and the Poetry Society of America’s di Castagnola Award, The World Doesn’t End: Prose Poems (1990), which won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (a prize for which he had been nominated on two previous occasions, in 1986 and 1987), Walking the Black Cat (1996), which was a finalist for the National Book Award, and Jackstraws (1999), which was nominated a Notable Book of the Year by the New York Times. Simic has also been honoured with two PEN Awards for his distinguished work as a translator (1970, 1980), a Guggenheim Fellowship (1972), two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships (1974, 1979), the American Academy of Poets’ Edgar Allan Poe Award (1975), the American Academy Award (1976), a Fulbright Fellowship (1982), an Ingram Merrill Fellowship (1983), a MacArthur Fellowship (1984), an Academy of American Poets’ Fellowship (1998), and the University of New Hampshire’s Lindberg Award “for his achievements as both an outstanding scholar and teacher in the College of Liberal Arts” (2002). In 2000, he was appointed a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, and a little earlier this year he was also elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Simic and his wife – who have a son and daughter – live in Strafford, New Hampshire.

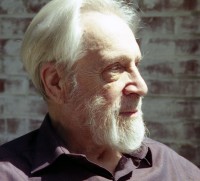

W.D. Snodgrass was born in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, in 1926, and was educated at Geneva College. His studies were interrupted when, during WWII, he was drafted into the Navy, and sent to the Pacific.

After demobilization, Snodgrass resumed his studies, but transferred from Geneva College to the University of Iowa, eventually enrolling in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, which had been established in 1937, and was attracting as tutors some of the finest poetic talents of the day, amongst them John Berryman, Randall Jarrell and Robert Lowell.

Snodgrass’s first poems appeared in 1951, and throughout the 1950’s he published in some of the most prestigious magazines (e.g. Botteghe Oscure, Partisan Review, the New Yorker, the Paris Review and the Hudson Review). However, in 1957, five sections from a sequence entitled ‘Heart’s Needle’ were included in Hall, Pack and Simpson’s anthology, New Poets of England and America, and these were to mark a turning-point. When Lowell had been shown early versions of these poems, in 1953, he had disliked them, but now he was full of admiration. He wrote to Elizabeth Bishop, saying: ‘I must tell you that I’ve discovered a new poet, W.D. Snodgrass – he was once one of my Iowa students, and I merely thought him about the best. Now he turns out to be better than anyone except Larkin.’He also wrote to Randall Jarrell, this time calling Snodgrass Larkin’s equal, and comparing him to the great French poet, Jules Laforgue. The point was developed in an interview he gave the Paris Review rather later:

‘I think a lot of the best poetry is [on the verge of being slight and sentimental]. Laforgue – it’s hard to think of a more delightful poet … Well, it’s on the verge of being sentimental, and if he hadn’t dared to be sentimental he wouldn’t have been a poet. I mean, his inspiration was that. There’s some way of distinguishing between false sentimentality, which is blowing up a subject and giving emotions that you don’t feel, and using whimsical, minute, tender, small emotions that most people don’t feel but which Laforgue and Snodgrass do. So that I’d say he [Snodgrass] had pathos and fragility … He has fragility along the edges and a main artery of power going through the center."

As well as writing to Bishop and Jarrell, Lowell wrote to Snodgrass, saying how much he admired the anthologized poems, and offering to help him find a book publisher.

By the time Heart’s Needle was published, in 1959, Snodgrass had already won the The Hudson Review Fellowship in Poetry and an Ingram Merrill Foundation Poetry Prize. However, his first book brought him something more: a citation from the Poetry Society of America, a grant from the National Institute of Arts, and, most important of all, 1960’s Pulitzer Prize in Poetry.

It is often said that Heart’s Needle inaugurated confessional verse. Snodgrass dislikes the term, and is quick to point out that the kind of verse he was writing at that time – a ‘searingly personal’ verse, as Ann Sexton called it – was hardly unprecedented. This is true, but it is also true that the genre he was reviving here seemed revolutionary to most of his contemporaries, reared as they had been on the anti-expressionistic principles of the New Critics.

Snodgrass’s confessional work was to have a profound effect on many of his contemporaries, amongst them, and most importantly, Robert Lowell. The evidence for this is on display in Lowell’s most accomplished volume, Life Studies, which appeared in the same year as Heart’s Needle, and enabled its author to carry off the other great literary prize for 1960, the National Book Award. The effect on other poets, on both sides of the Atlantic, is fairly described as liberating. As one English critic was to put it later on:

”’Confessional’ was an unfortunate way of describing what was new about Life Studies and Heart’s Needle – the term reeks of guilt and ingratiation – but it does recall the general surprise that such poetic vibrance and composure could be won from subjects that seemed doomed to privacy or narcissistic inflation."

In the almost forty years since this auspicious debut, Snodgrass has gone on to produce an impressively diverse body of work, including After Experience, Remains, A Locked House, W.D.’s Midnight Carnival, The Death of Cock Robin, Each in His Season, The Führer Bunker, seven volumes of translations, and a large number of essays too, some of which were collected in In Radical Pursuit. These books have seriously divided the critics, bringing bouquets from some and brickbats from others. Most controversial of all was The Führer Bunker, a book which not only pitted critics against each other, but in one notable case pitted a critic against himself.

Snodgrass has a long and distinguished academic career behind him, having taught at Cornell, Rochester, Wayne State, Syracuse, Old Dominion, and Delaware Universities. He retired from teaching in 1994, and now devotes himself full-time to his writing. He lives with his ‘fourth, last and best’ wife, the writer, Kathleen Snodgrass (née Browne), spending six months of each year at their home in New York, and the other six months in Mexico.

– Philip Hoy, 1998

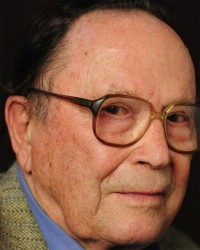

Richard Wilbur was born in New York City in 1921. His books of poetry include New and Collected Poems (1988), which won the Pulitzer Prize; The Mind-Reader: New Poems (1976); Walking to Sleep: New Poems and Translations (1969); Advice to a Prophet and Other Poems (1961); Things of This World (1956), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award; Ceremony and Other Poems (1950); and The Beautiful Changes and Other Poems (1947). He has also published numerous translations of French plays, two books for children, and a collection of prose pieces, and has edited such books as Poems of Shakespeare (1966) and The Complete Poems of Poe (1959). His The Catbird’s Song: Prose Pieces is due this spring from Harcourt Brace. Among his honors are the Wallace Stevens Award, the Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, the Frost Medal, the Gold Medal for Poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Bollingen Prize, the T. S. Eliot Award, a Ford Foundation Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, the Edna St. Vincent Millay Memorial Award, the Harriet Monroe Poetry Award, the National Arts Club medal of honor for literature, two PEN translation awards, the Prix de Rome Fellowship, and the Shelley Memorial Award. He was elected a chevalier of the Ordre des Palmes Académiques and is a former Poet Laureate of the United States. A Chancellor Emeritus of The Academy of American Poets, he lives in Cummington, Massachusetts.

Richard Wilbur was born in New York City in 1921. His books of poetry include New and Collected Poems (1988), which won the Pulitzer Prize; The Mind-Reader: New Poems (1976); Walking to Sleep: New Poems and Translations (1969); Advice to a Prophet and Other Poems (1961); Things of This World (1956), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award; Ceremony and Other Poems (1950); and The Beautiful Changes and Other Poems (1947). He has also published numerous translations of French plays, two books for children, and a collection of prose pieces, and has edited such books as Poems of Shakespeare (1966) and The Complete Poems of Poe (1959). His The Catbird’s Song: Prose Pieces is due this spring from Harcourt Brace. Among his honors are the Wallace Stevens Award, the Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, the Frost Medal, the Gold Medal for Poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Bollingen Prize, the T. S. Eliot Award, a Ford Foundation Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, the Edna St. Vincent Millay Memorial Award, the Harriet Monroe Poetry Award, the National Arts Club medal of honor for literature, two PEN translation awards, the Prix de Rome Fellowship, and the Shelley Memorial Award. He was elected a chevalier of the Ordre des Palmes Académiques and is a former Poet Laureate of the United States. A Chancellor Emeritus of The Academy of American Poets, he lives in Cummington, Massachusetts.

Interviewer

Mark Ford was born in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1962. He went to school in London, and attended Oxford and Harvard Universities. He wrote his doctorate at Oxford University on the poetry of John Ashbery, and has published widely on nineteenth- and twentieth-century American writing. From 1991-1993 he was Visiting Lecturer at Kyoto University in Japan. He currently teaches in the English Department at University College London, where he is a Senior Lecturer.

Ford has published two collections of poetry, Landlocked (Chatto & Windus, 1992;1998) and Soft Sift (Faber & Faber, 2001/Harcourt Brace, 2003), and has also written a critical biography of the French poet, playwright and novelist, Raymond Roussel, Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams (Faber & Faber, 2000/Cornell University Press, 2001). A Driftwood Altar, a collection of his essays and reviews, was published by The Waywiser Press in 2005.

He is a regular contributor to the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books and the New York Review of Books, amongst other journals.

Ian Hamilton was born in 1938, and educated at Darlington Grammar School and Keble College, Oxford. He co-founded and edited The Review (1962-1972), and the New Review (1974-1979), and was for several years poetry and fiction editor for the Times Literary Supplement (1965-1973).

His verse publications include: The Visit (Faber, London,1970), Fifty Poems (Faber, London, 1988), Steps (Cargo Press, 1997), and Sixty Poems (Faber, London, 1999). His prose publications include: A Poetry Chronicle: Essays and Reviews (Faber, London 1973/Barnes and Noble, NY, 1973), The Little Magazines: A Study of Six Editors (Weidenfeld, London, 1976), Robert Lowell: A Biography (Random House, NY, 1982/Faber, London, 1983), In Search of J.D. Salinger (Heinemann, London, 1988/Random House, NY, 1988), Writers in Hollywood, 1915-1951 (Heinemann, London, 1990/Harper, NY, 1990), Keepers of the Flame (Hutchinson, London, 1992), The Faber Book of Soccer (Faber, London, 1992), Gazza Agonistes (Granta/Penguin, London, 1994), Walking Possession (Bloomsbury, London, 1994), A Gift Imprisoned: The Poetic Life of Matthew Arnold (Bloomsbury, London, 1998), The Trouble with Money and Other Essays (Bloomsbury, London, 1998), and Anthony Thwaite in Conversation with Peter Dale and Ian Hamilton (BTL, London, 1999).

Hamilton has also edited a large number of books, amongst them: The Poetry of War, 1939-45 (Alan Ross, London,1965), Alun Lewis: Selected Poetry and Prose (Allen and Unwin, London, 1966), The Modern Poet: Essays from ‘The Review’ (Macdonald, London,1968/Horizon, NY, 1969), Eight Poets (Poetry Book Society, London, 1968), Robert Frost: Selected Poems (Penguin, London, 1973), Poems Since 1900: an Anthology of British and American Verse in the Twentieth Century (with Colin Falck) (Macdonald and Jane’s, London, 1975), Yorkshire and Verse (Secker and Warburg, London, 1984), The ‘New Review’ Anthology (Heinemann, London, 1985), Soho Square (2) (Bloomsbury, London, 1989), the Oxford Companion to 20th Century Poetry (OUP, Oxford, 1996), and the Penguin Book of Twentieth-Century Essays (Penguin, London, 1999).

Between 1984 and 1987 Hamilton presented BBC TV’s Bookmark programme. He now serves on the editorial board of The London Review of Books.

2000

Ian Hamilton, one of the founding editors of Between The Lines, died on December 27, 2001.

Philip Hoy was born in 1952, and educated at Glastonbury High School in Surrey, and at the Universities of York and Leeds. He has a Ph.D in Philosophy, a subject he taught for many years, in the UK, and, more recently, overseas. Since returning to the UK, in 1996, Hoy has been writing, editing and publishing. His most recent publications include "The Starry Night": Snodgrass's Van Gogh Reconsidered' (Agenda, London, 1996), "The Genesis of On Certainty: Some Questions for Professors Anscombe and von Wright' (Wittgenstein Studien, University of Passau, 1996), the proem and afterword to Peter Dale's Da Capo (Agenda Editions, London, 1997), "The Will to Power #486/KGW VIII, 1 2[87], 2: A Knot that Won't Unravel?" (Nietzsche Studien, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1998), W.D. Snodgrass in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1998), Anthony Hecht in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1999, 2001, 2004), Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 2001), "The Interviewer Interviewed: N.S Thompson talks to Philip Hoy, editor of Between The Lines", The Dark Horse, 15, Summer 2003: 40-46. (If you would like to read this article, please follow this link: http://www.waywiser-press.com/imprints/darkhorse.html).

Philip Hoy was born in 1952, and educated at Glastonbury High School in Surrey, and at the Universities of York and Leeds. He has a Ph.D in Philosophy, a subject he taught for many years, in the UK, and, more recently, overseas. Since returning to the UK, in 1996, Hoy has been writing, editing and publishing. His most recent publications include "The Starry Night": Snodgrass's Van Gogh Reconsidered' (Agenda, London, 1996), "The Genesis of On Certainty: Some Questions for Professors Anscombe and von Wright' (Wittgenstein Studien, University of Passau, 1996), the proem and afterword to Peter Dale's Da Capo (Agenda Editions, London, 1997), "The Will to Power #486/KGW VIII, 1 2[87], 2: A Knot that Won't Unravel?" (Nietzsche Studien, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1998), W.D. Snodgrass in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1998), Anthony Hecht in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 1999, 2001, 2004), Donald Justice in Conversation with Philip Hoy (BTL, London, 2001), "The Interviewer Interviewed: N.S Thompson talks to Philip Hoy, editor of Between The Lines", The Dark Horse, 15, Summer 2003: 40-46. (If you would like to read this article, please follow this link: http://www.waywiser-press.com/imprints/darkhorse.html).

Hoy is managing editor of Between The Lines, and executive editor too of The Waywiser Press, the press of which BTL is an imprint. He lives in Surrey.

Michael Hulse was born in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire in 1955, and educated locally (1966-1971) and at the University of St Andrews (1973-1977), where he took an MA in German. From the late Seventies until very recently, he lived in Germany, working as a university lecturer, and as an editor, reviewer, translator and publisher.

Michael Hulse was born in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire in 1955, and educated locally (1966-1971) and at the University of St Andrews (1973-1977), where he took an MA in German. From the late Seventies until very recently, he lived in Germany, working as a university lecturer, and as an editor, reviewer, translator and publisher.

Hulse’s poetry collections include Knowing and Forgetting (Secker and Warburg, London, 1981), Propaganda (Secker and Warburg, London 1985), and Eating Strawberries in the Necropolis (Collins Harvill, London, 1991). Empires and Holy Lands: Poems 1976-2000, appeared from Salt Publishing (Cambridge) in 2002.

Amongst the fifty or more books Hulse has translated into English are J.W. Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther (Penguin, London, 1989), Jakob Wassermann’s Caspar Hauser (Penguin, London, 1992), Botho Strauss’s Tumult (Carcanet, Manchester/New York, 1984), and W.G. Sebald’s The Emigrants (Harvill, London/New Directions, New York, 1996), The Rings of Saturn (Harvill, London/New Directions, New York, 1998) and Vertigo (Harvill, London/New Directions, New York, 1999).

Hulse teaches on the Writing Programme at the University of Warwick.

Peter Dale was born in Surrey in 1938, and educated at Strode’s School, Egham, and St Peter’s College, Oxford. For twenty-one years he was head of the English department of Hinchley Wood School, Esher, and concurrently an editor of the poetry quarterly Agenda. Well-known for his Penguin verse-translation of Villon, he has recently published a terza-rima version of Dante’s Divine Comedy and his selected poems, Edge to Edge, both with Anvil Press Poetry Ltd. His Richard Wilbur in Conversation with Peter Dale was published by Between The Lines in 2000. Revised and extended editions of his Poems of François Villon and his Poems of Jules Laforgue appeared from Anvil in 2001. He currently edits a poetry column for Oxford Today.

Interviewee

John Lawrence Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York, on July 28th 1927, the first son of Chester Frederick (a farmer) and Helen Ashbery (a biology teacher). He went to school in Rochester and in his home town of Sodus, and at the age of sixteen was sent as a boarder to Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. After graduating from there, in 1945, he entered Harvard University, where he studied English.

John Lawrence Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York, on July 28th 1927, the first son of Chester Frederick (a farmer) and Helen Ashbery (a biology teacher). He went to school in Rochester and in his home town of Sodus, and at the age of sixteen was sent as a boarder to Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. After graduating from there, in 1945, he entered Harvard University, where he studied English.

Ashbery had been writing poetry since his schooldays, and while at Deerfield had even had two of his poems accepted by the prestigious magazine, Poetry. Two years after he went to college he submitted work to The Harvard Advocate, the recently revived undergraduate magazine, whose editors were Robert Bly, Donald Hall and Kenneth Koch. The poems were quickly published, and just a few months later their author found himself installed as the fourth member of the magazine’s editorial board. According to Hall, he rapidly became the Advocate’s leading light.

Ashbery obtained his BA in 1949, and went to Columbia University to study for his MA. He graduated from there in 1951, and found work in publishing, becoming a copywriter, first for Oxford University Press and then for the McGraw Hill Book Company. Poems of his continued to appear in magazines, amongst them Furioso, Poetry New York and Partisan Review, but as well as pursuing his literary interests, Ashbery was now mixing in New York’s artistic circles, frequenting the galleries, and getting to know the painters. Then, in 1953, thanks to its director, John Myers, the city’s influential Tibor de Nagy Gallery published a slender chapbook of Ashbery’s poems, complete with illustrations by the artist Jane Freilicher. Turandot and Other Poems seems not to have attracted much notice, but Alfred Corn subsequently included its publication in a list of the most important events ‘in the history of twentieth century avant-garde art’.

Three years later, by which time he was in Paris on a Fulbright fellowship, Ashbery’s first full collection was chosen by W.H. Auden for inclusion in Yale University Press’s Younger Poets Series. Reviewing Some Trees for Poetry, Frank O’Hara wrote of Ashbery’s ‘faultless music’ and ‘originality of perception’, and pronounced it ‘the most beautiful first book to appear in America since Harmonium’. Not everyone felt so enthusiastic, however. William Arrowsmith, writing for The Hudson Review, declared that he had ‘no idea most of the time what Mr Ashbery is talking about ... beyond the communication of an intolerable vagueness that looks as if it was meant for precision,’ and added, for good measure: ‘What does come through is an impression of an impossibly fractured brittle world, depersonalized and discontinuous, whose characteristic emotional gesture is an effete and cerebral whimsy.’

Ashbery’s period as a Fulbright fellow came to an end in 1957, but life in Paris had been so much to his liking that, after another year in the US – a year in which he took graduate classes at New York University and worked as an instructor in elementary French – he returned, avowedly to pursue research for a doctoral dissertation on the writer Raymond Roussel. He was to remain in France for several years, supporting himself by writing for a number of different journals. He had started to review for the magazine ArtNews during his year in New York, and continued with this once back in Paris. Then, in 1960, he became art critic for the New York Herald Tribune (international edition), and, in 1961, art critic for Art International as well. Nor were these his only such commitments. In the same year that he started writing for the New York Herald Tribune, he joined with Kenneth Koch, Harry Mathews, and James Schuyler and founded the literary magazine, Locus Solus. That folded in 1962, but the following year he got together with Anne Dunn, Rodrigo Moynihan and Sonia Orwell, and founded Art and Literature, a quarterly review he worked on until he went back to living in the US, in 1966.

When not writing reviews, or engaged in editorial work, Ashbery still found time to write poetry. It was poetry of a very different kind to that he had published in Some Trees, however, and readers familiar with the first book will have been altogether unprepared for the ‘violently experimental’ character of the second (unless they had been keeping an eye on Big Table and Locus Solus, the magazines in which some of these poems first appeared). Reactions to The Tennis Court Oath were generally hostile. James Schevill told readers of the Saturday Review: ‘The trouble with Ashbery’s work is that he is influenced by modern painting to the point where he tries to apply words to the page as if they were abstract, emotional colors and shapes ... Consequently, his work loses coherence ... There is little substance to the poems in this book.’ And Mona Van Duyn told readers of Poetry: ‘If a state of continuous exasperation, a continuous frustration of expectation, a continuous titillation of the imagination are sufficient response to a series of thirty-one poems, then these have been successful. But to be satisfied with such a response I must change my notion of poetry.’ Even so devoted an admirer of Ashbery as Harold Bloom thought the book a ‘fearful disaster’ and confessed to being baffled at how its author could have ‘collapse[d] into such a bog’ just six years after Some Trees.

Ashbery has said that when he was working on the poems that went into The Tennis Court Oath he was ‘taking language apart so I could look at the pieces that made it up’, and that after he’d done this he was intent on ‘putting [the pieces] back together again’. Rivers and Mountains, published in the year that he settled back in the US, was the first of his books to follow, and marked what several of his critics regard as his real arrival as a poet, with poems such as “These Lacustrine Cities”, “Clepsydra” and “The Skaters” all demonstrating for the first time what one of them has called the ‘astonishing range and flexibility of Ashbery’s voice’. The volume was nominated for the National Book Award.

Ashbery had gone back to the US after being offered the job of executive editor of ArtNews. Four years later, in 1969, the Black Sparrow Press published his long poem “Fragment”, with illustrations by the painter Alex Katz. Writing about this seven years on, Bloom declared that it was, for him, Ashbery’s ‘finest work’. By then, it should be noted, the poem had plenty of rivals, since The Double Dream of Spring (which included “Fragment”) had appeared in 1970, Three Poems had appeared in 1972, and The Vermont Notebook and Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror had appeared in 1975. All of these books had won Ashbery admiring notices, and Three Poems had also secured him the Modern Poetry Association’s Frank O’Hara Prize, but it was Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror that proved to be the breakthrough, carrying off all three of America’s most important literary prizes – the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. John Malcolm Brinnin’s notice for the New York Times Book Review can be taken as representative: ‘[A] collection of poems of breathtaking freshness and adventure in which dazzling orchestrations of language open up whole areas of consciousness no other American poet has even begun to explore ...‘

ArtNews was sold in 1972, and Ashbery had to find himself another job. A Guggenheim Fellowship sustained him for some months, but then, in 1974, he took up the offer of a teaching post at Brooklyn College – a part of the City University of New York – where he co-directed the MFA program in creative writing. Though he has confessed to not liking teaching very much, he has been doing it ever since (with one extended break between 1985 and 1990, made possible by the award of a MacArthur Foundation fellowship). He left Brooklyn College in 1990, was Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard between 1989 and 1990, and from then until now has been Charles P. Stevenson, Jr. Professor of Languages and Literature at Bard College at Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Just as Ashbery’s art reviewing and editorial work seemed not to affect his creative output during the Sixties and early Seventies, so his teaching work seems not to have affected it during the decades since. In fact, he has been remarkably prolific, averaging a new collection once every eighteen months. Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror was followed by: Houseboat Days (1977), As We Know (1979), Shadow Train (1981), A Wave (1984), April Galleons (1987), Flow Chart (1991), Hotel Lautréamont (1992), And the Stars Were Shining (1994), Can You Hear, Bird (1995), Wakefulness (1998), Girls on the Run (1999), Your Name Here (2000), As Umbrellas Follow Rain (2001) and Chinese Whispers (2002) (to mention only his book-length collections). He has also published Three Plays (1978), Reported Sightings (a selection of his art reviews) (1989) and Other Traditions (revised versions of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures he gave in 1989 and 1990).

This large body of work has won Ashbery numerous admirers, amongst them some of today’s most prominent critics. It has also won him numerous honours, awards and prizes, a partial list of which would include (apart from those already mentioned) two Ingram Merrill Foundation grants (1962, 1972), Poetry magazine’s Harriet Monroe Poetry Award (1963) and Union League Civic and Arts Foundation Prize (1966), two Guggenheim fellowships (1967, 1973), two National Endowment for the Arts publication awards (1969, 1970), the Poetry Society of America’s Shelley Memorial Award (1973), Poetry magazine’s Levinson Prize (1977), a National Endowment for the Arts Composer/Librettist grant (with Elliott Carter) (1978), a Rockefeller Foundation grant for playwriting (1979-1980), the English Speaking Union Award (1979), membership of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (1980), fellowship of the Academy of American Poets (1982), the New York City Mayor’s Award of Honour for Arts and Culture, Bard College’s Charles Flint Kellogg Award in Art and Letters, membership of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1983), American Poetry Review’s Jerome J. Shestack Poetry Award (1983, 1995), Nation magazine’s Lenore Marshall Award, the Bollingen Prize, Timothy Dwight College/Yale University’s Wallace Stevens fellowship (1985), the MLA Common Wealth Award in Literature (1986), the American Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award (1987), Chancellorship of the Academy of American Poets (1988-1989), Brandeis University’s Creative Arts Award in Poetry (Medal) (1989), the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts (Munich)’s Horst Bienek Prize for Poetry (1991), Poetry magazine’s Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Academia Nazionale dei Lincei (Rome)’s Antonio Feltrinelli International Prize for Poetry (1992), the French Ministry of Education and Culture (Paris)’s Chevalier de L’Ordre des Arts et Lettres (1993), the Poetry Society of America’s Robert Frost Medal (1995), the Grand Prix des Biennales Internationales de Poésie (Brussels), the Silver Medal of the City of Paris (1996), the American Academy of Arts and Letters’s Gold Medal for Poetry (1997), Boston Review of Books’s Bingham Poetry Prize (1998), the State of New York/New York State Writers Institute’s Walt Whitman Citation of Merit (2000), Columbia County (New York) Council on the Arts Special Citation for Literature, the Academy of American Poets’s Wallace Stevens Award, Harvard University’s Signet Society Medal for Achievement in the Arts (2001), the New York State Poet Laureateship (2001-2002), and France’s Officier de la Légion d’Honneur (2002).

Ashbery lives in the Chelsea district of New York City and in Hudson, New York.

Donald Hall was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1928, the only child of Donald Andrew Hall (a businessman) and his wife Lucy (née Wells). He was educated at Phillips Exeter, New Hampshire, and at the Universities of Harvard, Oxford and Stanford.

Hall began writing even before reaching his teens, beginning with poems and short stories, and then moving on to novels and dramatic verse. He recalls the powerful influence on his youthful imagination of Edgar Allan Poe: ‘I wanted to be mad, addicted, obsessed, haunted and cursed. I wanted to have deep eyes that burned like coals – profoundly melancholic, profoundly attractive.’

Hall continued to write throughout his prep school years at Exeter Phillips, and, while still only sixteen years old, attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, where he made his first acquaintance with the poet Robert Frost. That same year, he published his first work.

While an undergraduate at Harvard, Hall served on the editorial board of the Harvard Advocate, and got to know a number of people who, like him, were poised for significant things in the literary world, amongst them John Ashbery, Robert Bly, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, and Adrienne Rich.

After leaving Harvard, Hall went to Oxford for two years, to study for the B.Litt. While there, he found time not only to edit The Fantasy Poets – in which capacity, he published first volumes by two more people who were set to make their mark on the literary world, Thom Gunn and Geoffrey Hill – but also to maintain four other valuable positions, as editor of the Oxford Poetry Society’s journal, as literary editor of Isis, as editor of New Poems, and as poetry editor of the Paris Review. At the end of his first Oxford year, Hall also won the university’s prestigious Newdigate Prize, awarded for his long poem, ‘Exile’.

On returning to the United States, Hall went to Stanford, where he spent one year as a Creative Writing Fellow, studying under the poet-critic, Yvor Winters. In Their Ancient Glittering Eyes – a book which merits comparison with Hazlitt’s ‘My First Acquaintance with Poets’ – he recalls Winters greeting him with the words, ‘You come from Harvard, where they think I’m lower than the carpet,’ adding, after a pause, ‘Do you realize that you will be ridiculed, the rest of your life, for having studied a year with me?’

Following his year at Stanford, Hall went back to Harvard, where he spent three years in the Society of Fellows. During that time, he put together his first book, Exiles and Marriages, and with Robert Pack and Louis Simpson also edited an anthology which was to make a significant impression on both sides of the Atlantic, The New Poets of England and America.

Hall was appointed to the faculty in the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in 1957, and apart from two one-year breaks in England continued to teach there until 1975, when, after three years of marriage to his second wife, the poet Jane Kenyon, he abandoned the security of his academic career, and went with her to live in rural New Hampshire, on the farm settled by his maternal great-grandfather over one hundred years earlier.

Ever since that time, Hall has supported himself by writing. When not working on poems, he has turned his hand to reviews, criticism, textbooks, sports journalism, memoirs, biographies, children’s stories, and plays. He has also devoted a lot of time to editing: between 1983 and 1996 he oversaw publication of more than sixty titles for the University of Michigan Press alone. At one time, Hall estimated that he was publishing a minimum of one item per week, and four books a year.

In 1989, when Hall was sixty-one, it was discovered that he had colon cancer. Surgery followed, but by 1992 the cancer had metastasized to his liver. After another operation, and chemotherapy, he went into remission, though he was told that he only had a one-in-three chance of surviving the next five years. Then, early in 1994, when the thought uppermost in his and his wife’s minds was that his own cancer might re-appear, it was discovered that she had leukaemia. Her illness, her death fifteen months later, and Hall’s struggle to come to terms with these things, were the subject of his most recent book, Without.