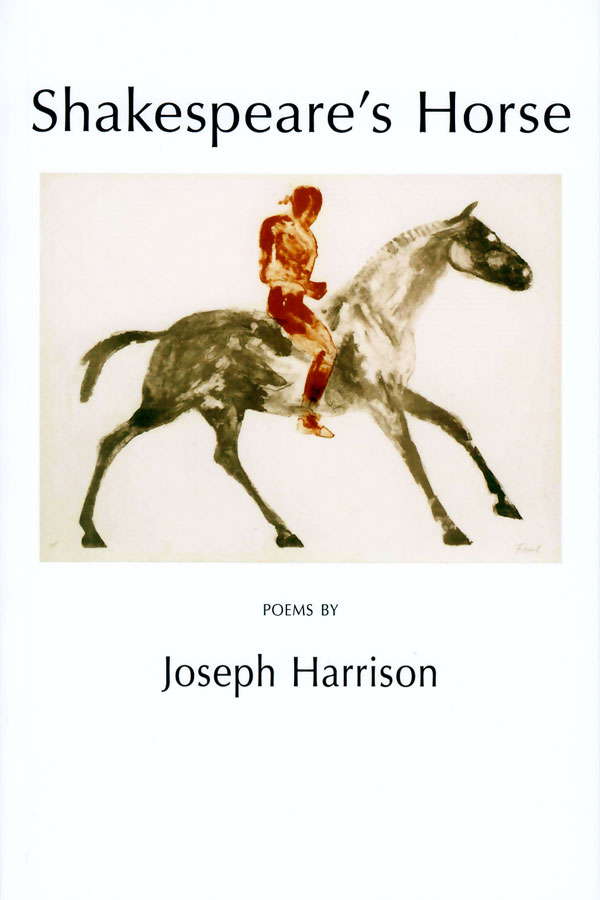

Shakespeare’s Horse

£9.99 / £11.99

Joseph Harrison’s third collection of poetry displays all the formal adroitness that characterized his two previous books, now applied to a greater range of subjects and poetic genres. Poems that speak to our current condition and poems in various historical settings, evocations of Italian and Latin precursors as well as English and American ones, and forms that range from short lyrics to longer meditations in blank verse and terza rima combine to produce a volume of extraordinary variety and scope. Shakespeare’s Horse blends the past with the present, the personal with the universal, and a resonant music with an idiosyncratic vision that sees the world afresh.

Shakespeare’s Horse

“Shakespeare’s Horse is Joseph Harrison’s full emergence as his own poet, still in the eloquent and formal tradition of Richard Wilbur and Anthony Hecht but with an accent now pitched in a new mode. Among the book’s triumphs are “Wakefield,” the wonderful “Dr. Johnson Rolls Down a Hill,” “Damon,” and “Harrison’s Clock.” Yet I take a particular joy in the brief and enigmatic “Hamlet” and the remarkable title sonnet.

The kind of comedy that Harrison works into his subtle meditations is refreshingly original. Should he further refine his already agile art, there will be no one in his American generation who so challenges the eye and the ear to come together.” – Harold Bloom

"Joseph Harrison’s poetry is modern without being modernist. That is, he employs the tools and materials of traditional poetry to construct a kind of verse that is appealingly new, yet never transgressively so. His poems reflect a renewed lustre in our direction, and we come away deeply refreshed. – John Ashbery

Reviews of Shakespeare’s Horse

The Hopkins Review, 8:4, Fall 2015 (New Series)

The poems in Joseph Harrison’s Shakespeare’s Horse might best be dubbed encyclopoetry. These are poems steeped in learning, in history, in facts …. Take “Dr. Johnson Rolls Down a Hill,” among the volume’s finest poems. One can read the poem without knowing much more than Johnson’s reputation as the Great English Critic who looms over the canon with a discerning eye. Harrison’s poem spells out its own occasion, with a first stanza emphasizing that ‘Even a man of voluminous gravity,’ ‘Who relished with dispatch and enormous zest / Huge stacks of pancakes, bottomless pots of tea, . . . Contains in his heart of hearts a little boy / Who played and played all day.’ And so we are led through the heavy vagaries of Johnson’s life, only to find ourselves at a scene (a real one, in fact) where Johnson is with company at the top of hill. He ‘divests himself of pencil, keys, and purse’ and then simply lets himself roll down the hill ‘As if the good life really were this easy, / As if the nightmare of his coming breakdown / Had no more substance than a child’s bad dream.’ It’s a moving passage, and one that shows the formidable Johnson’s melancholy, human side. This poem, like almost every poem in the volume, is written in fluid meter. Many of them rhyme, as well. Harrison’s attitude about form seems like the opposite of Robert Lowell’s, who wanted rhyme and meter to look hard, and who wrote as though form were a way of showing the seriousness of your message. Harrison is more like Yeats; he makes form look easy, and his poems are better for it, as in the first stanza of ‘The Key’:

Here is the key. The lock is on the door

Of a small cabin in a distant wood

Standing for something you’ve never understood,

An emptiness that’s full of metaphor.

That’s behind-the-scenes form at its finest; the metrical inversions are perfectly measured, and the way he rhymes monosyllables with trisyllables cuts out any hint of clunkiness. The book’s variety is also winning, with a range of traditional and nonce forms. – Joey Frantz

Praise for Harrison’s earlier collections

“Joseph Harrison writes like an angel.” – Rachel Hadas

“Mr. Harrison’s technique never fails him, his capacity for conveying the deepest and most subtle feelings is sure and accurate. Best of all … the reader will encounter the sheer joy of a poet gladdened by his own art, alive to the liberties and limits of form and imagination – playful, serious, gifted, multi-vocal, and athletically adroit.” – Anthony Hecht

“Someone Else’s Name is a first book full of stunning performances, each one infused with wit, feeling, and humanity, and each one delighting in the full use of the medium and its devices. It’s a happy thing to witness the emergence of such a talent.” – Richard Wilbur

“The poems is this first book are so witty and formally adept, so technically accomplished, that they almost seem to have come from another era.” – Edward Hirsch

“Joseph Harrison’s outstanding first book of poems … is marked by a rare stylistic authority and imaginative energy, and by … the mutual animation of deep poetic learning and passionate responses to immediate experience.” – American Academy of Arts and Letters.

“Joseph Harrison’s new volume [Identity Theft] is a wonderful leap in his poetic development. Harrison fuses formal control with a rich interiority and composes many poems that deserve to become canonical.” – Harold Bloom

“How deeply satisfying it is to read a poet whose meditative, elegiac temperament is married happily to verbal wit, even laugh-out-loud humor. Joseph Harrison is that rare poet, one whose command of craft suits him equally to produce a two-line ‘Ode’ (‘O elevated visionary thoughts, / Where are you now?’) and a ten-page public poem (‘To George Washington in Baltimore’) on that American giant who understood the ‘human scale.’ A poet so giddy with wordplay that he dares to rhyme ‘my palm is piloted’ with ‘Pontius Pilated’ and ‘pirated,’ Harrison addresses nonetheless the most serious concerns. Wary of our technology-dominated present and future, in which ‘identity theft’ is no joke (and ‘what fave new world is beckoning?’), Harrison makes his fingerprint evident in all of these poems – an implicit affirmation of something unique in each of us.” – Mary Jo Salter

“The title poem of Joseph Harrison’s second book is a witty and headlong discussion of how one’s self, if any, is constituted. We are a patchwork, it develops, and the same might be said of Harrison’s book, which makes continual and expert use of Spenser, Wordsworth, Horace, Villon, and other predecessors. If this makes Identity Theft seem a three-ring circus, the important point is that Harrison is a superlative ringmaster: his book throughout is governed by that playfulness and performance which, as Frost said, are required in poetry however impassioned or serious. I found myself particularly moved by ‘Who They Were,’ which recalls the poet’s mother and father in the stanza of Tennyson’s ‘In Memoriam’.” – Richard Wilbur

“Harrison is the author of two remarkable books: Someone Else’s Name … and Identity Theft … He is a consummate craftsman … He uses language with exquisite precision to register the erosion of language and in this … he is both irrepressibly humorous and scathingly satirical. Harrison is a poet of great formal flamboyance. There seems to be no measure, no verse-form, at which he is not quite utterly dazzling. His poems exhibit a resonant awareness of the entire tradition of English verse and he’s not diffident about displaying it. If he revels in echoes, these are mastered echoes, audaciously launched both in homage to tradition and its defence … Perhaps it will sound solemn to call … Joseph Harrison [a poet] by vocation. But the wit, the beauty and the brilliant strangeness of [his] poems – perhaps even [his] inspired mischief – come with the calling. And luckily for us, [he’s] … ‘having a good time’. – Eric Ormsby

Shakespeare’s Horse

He was a man knew horses, so we moved

As wills were one, and all was won at will,

In hand with such sleight handling as improved

Those parks and parcels where we’re racing still,

Pounding like pairs of hooves or pairs of hearts

Through woodland scenes and lush, dramatic spaces,

With all our parts in play to play all parts

In pace with pace to put us through his paces.

Ages have passed. All channels channel what

Imagined these green plots and gave them names

Down to the smallest role, if and and but,

What flies the time (the globe gone up in flames),

What thunders back to ring the ringing course

And runs like the streaking will, like Shakespeare’s horse.

The Waywiser Press

Dr. Johnson Rolls Down a Hill

Even a man of voluminous gravity,

The monumental lexicographer

Who labored in inconvenience and distraction,

In sorrow, sickness, and slovenly poverty

Unaided by the learned or the great,

A man of girth and passionate appetite

Who relished with dispatch and enormous zest

Huge stacks of pancakes, bottomless pots of tea,

Along with whatever conversational thrust

Kept the mind nimble and the spirit light,

Delaying the final, agonizing hour

When he lumbered off to bed, always alone,

To self-recrimination in pitch dark,

Contains in his heart of hearts a little boy

Who played and played all day, without a thought

Of duty or expectation or penury

Or wasted years diminishing all the time.

Not to idealize childhood, least of all his:

Barely alive at birth, too weak to cry,

Infected in infancy by tubercular milk,

Rendered half blind, half deaf, with an open wound

Stitched in his little arm for his first six years

(An issue, with so much else, he learned to ignore),

Scarred by the scrofula, and further scarred

By being cut sans anesthesia,

He wasn’t a pretty sight, but bore it all,

The constant pain, the perpetual awkwardness,

The fretting of parents, and the feckless taunts

Of boys who could play ball and ridicule

The rawboned, driveling prodigy in their midst,

And grew to be a man of great physical strength

Despite his pitiful incapacities.

The body had its struggles. So did the mind.

The photographic memory, the sheer

Celerity and clarity and taut

Engagement with the question, small or large,

Be it some pressing affair of state, or some

Domestic crisis pressing upon the heart

Of one he loved, encompassing his point

With honesty and syntax and good sense,

Such gifts the mind deployed with bravery

While poised above a vertiginous abyss

Opening wide within, a whirligig

Of deep afflictions and anxieties:

Depression, sloth, despair, paralysis,

An “inward hostility against himself”

In which his massive critical faculty

Would pulverize his puny self-regard,

And, worst of all, pure terror at the dark

Encroachments of what seemed insanity.

Now, in his middle fifties, the shadows lengthen,

“A kind of strange oblivion” overspreads him.

Beset by horrors and perplexities,

The clicks and spasms and clucking of Tourette’s

Markedly worsen as the great man sinks

Deeper in torpor, till guilt at time misspent

Freezes and harrows him, transfixed, become

A spectator at his own stunned debacle,

Tortured by scruples like pebbles in his shoes.

He’s written nothing for years, and Shakespeare waits,

Promised and paid for but beyond him still

(What infinite riches, and what little room),

As vast resources of intelligence

Fritter away from faulty “character,”

And reason flickers, dying, all but snuffed

Out by the listless drift of hopelessness.

His friends try to distract him, to little avail,

With a club, a trip to the country, anything. . . .

He visits Lincolnshire with Bennet Langton

In January 1764.

He’s on his best behavior, charming both

His young friend’s parents and their visitors.

One fine, dry afternoon, windless and clear,

They set out walking on the Lincolnshire wolds.

Only the groundsel’s in bloom, a tentative yellow,

As they amble past tufts of grouse scrub, furze, and thorn,

But the air has a pleasing crispness, with a rich,

Effluvial hint of leaf-mold or of wood-rot.

The hills are varied by streaks of yellowish red

Which vaguely correspond to, lower down,

The low, red roofs of occasional cottages.

Everything’s very still. There are just three birds:

A fluttering brace of fieldfares (or are they redwings?),

Plus a lone kestrel, hovering for a vole.

They reach the top of an impressive hill.

Admiring its steepness, suddenly Johnson declares

He has “not had a roll for a long time.”

Against the objections of the company

He divests himself of pencil, keys, and purse,

Lies down at the edge, and, after a turn

Or two, is off and tumbling and picking up speed

Flattening the flora in his path

While sending up puffs of chalk dust, now he’s chuckling

As his weight propels him and his heaviness

Precipitating his new view revolves

As sky and earth wheel round in blue-brown circles

And happiness is merely being alive,

As if the good life really were this easy,

As if the nightmare of his coming breakdown

Had no more substance than a child’s bad dream.

The Waywiser Press

Excerpts

Shakespeare's Horse

He was a man knew horses, so we moved

As wills were one, and all was won at will,

In hand with such sleight handling as improved

Those parks and parcels where we’re racing still,

Pounding like pairs of hooves or pairs of hearts

Through woodland scenes and lush, dramatic spaces,

With all our parts in play to play all parts

In pace with pace to put us through his paces.

Ages have passed. All channels channel what

Imagined these green plots and gave them names

Down to the smallest role, if and and but,

What flies the time (the globe gone up in flames),

What thunders back to ring the ringing course

And runs like the streaking will, like Shakespeare’s horse.

The Waywiser Press

Dr. Johnson Rolls Down a Hill

Even a man of voluminous gravity,

The monumental lexicographer

Who labored in inconvenience and distraction,

In sorrow, sickness, and slovenly poverty

Unaided by the learned or the great,

A man of girth and passionate appetite

Who relished with dispatch and enormous zest

Huge stacks of pancakes, bottomless pots of tea,

Along with whatever conversational thrust

Kept the mind nimble and the spirit light,

Delaying the final, agonizing hour

When he lumbered off to bed, always alone,

To self-recrimination in pitch dark,

Contains in his heart of hearts a little boy

Who played and played all day, without a thought

Of duty or expectation or penury

Or wasted years diminishing all the time.

Not to idealize childhood, least of all his:

Barely alive at birth, too weak to cry,

Infected in infancy by tubercular milk,

Rendered half blind, half deaf, with an open wound

Stitched in his little arm for his first six years

(An issue, with so much else, he learned to ignore),

Scarred by the scrofula, and further scarred

By being cut sans anesthesia,

He wasn’t a pretty sight, but bore it all,

The constant pain, the perpetual awkwardness,

The fretting of parents, and the feckless taunts

Of boys who could play ball and ridicule

The rawboned, driveling prodigy in their midst,

And grew to be a man of great physical strength

Despite his pitiful incapacities.

The body had its struggles. So did the mind.

The photographic memory, the sheer

Celerity and clarity and taut

Engagement with the question, small or large,

Be it some pressing affair of state, or some

Domestic crisis pressing upon the heart

Of one he loved, encompassing his point

With honesty and syntax and good sense,

Such gifts the mind deployed with bravery

While poised above a vertiginous abyss

Opening wide within, a whirligig

Of deep afflictions and anxieties:

Depression, sloth, despair, paralysis,

An “inward hostility against himself”

In which his massive critical faculty

Would pulverize his puny self-regard,

And, worst of all, pure terror at the dark

Encroachments of what seemed insanity.

Now, in his middle fifties, the shadows lengthen,

“A kind of strange oblivion” overspreads him.

Beset by horrors and perplexities,

The clicks and spasms and clucking of Tourette’s

Markedly worsen as the great man sinks

Deeper in torpor, till guilt at time misspent

Freezes and harrows him, transfixed, become

A spectator at his own stunned debacle,

Tortured by scruples like pebbles in his shoes.

He’s written nothing for years, and Shakespeare waits,

Promised and paid for but beyond him still

(What infinite riches, and what little room),

As vast resources of intelligence

Fritter away from faulty “character,”

And reason flickers, dying, all but snuffed

Out by the listless drift of hopelessness.

His friends try to distract him, to little avail,

With a club, a trip to the country, anything. . . .

He visits Lincolnshire with Bennet Langton

In January 1764.

He’s on his best behavior, charming both

His young friend’s parents and their visitors.

One fine, dry afternoon, windless and clear,

They set out walking on the Lincolnshire wolds.

Only the groundsel’s in bloom, a tentative yellow,

As they amble past tufts of grouse scrub, furze, and thorn,

But the air has a pleasing crispness, with a rich,

Effluvial hint of leaf-mold or of wood-rot.

The hills are varied by streaks of yellowish red

Which vaguely correspond to, lower down,

The low, red roofs of occasional cottages.

Everything’s very still. There are just three birds:

A fluttering brace of fieldfares (or are they redwings?),

Plus a lone kestrel, hovering for a vole.

They reach the top of an impressive hill.

Admiring its steepness, suddenly Johnson declares

He has “not had a roll for a long time.”

Against the objections of the company

He divests himself of pencil, keys, and purse,

Lies down at the edge, and, after a turn

Or two, is off and tumbling and picking up speed

Flattening the flora in his path

While sending up puffs of chalk dust, now he’s chuckling

As his weight propels him and his heaviness

Precipitating his new view revolves

As sky and earth wheel round in blue-brown circles

And happiness is merely being alive,

As if the good life really were this easy,

As if the nightmare of his coming breakdown

Had no more substance than a child’s bad dream.

The Waywiser Press