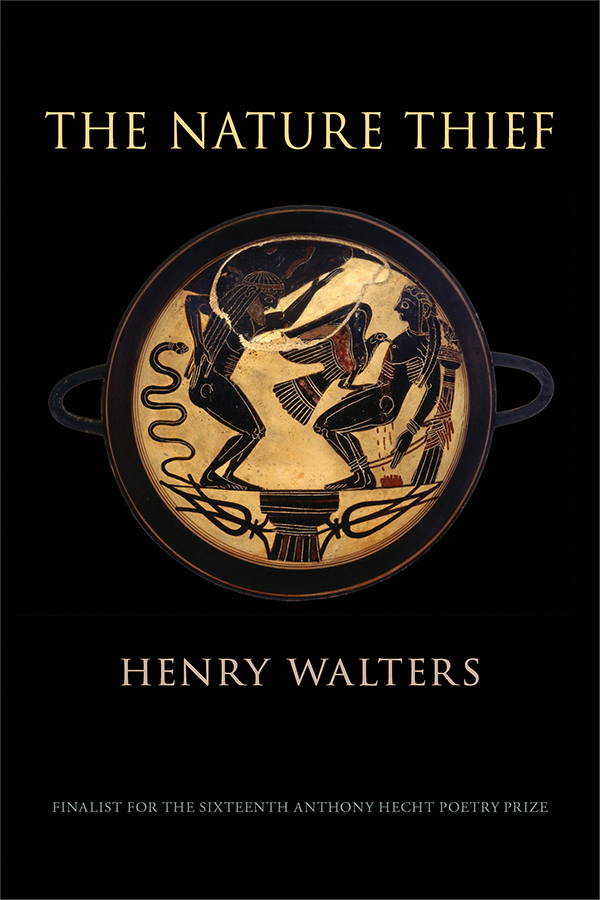

The Nature Thief

£10.99

Finalist for the sixteenth Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize

A compendium of clues and the mysteries they point to, The Nature Thief begins in the shadow of a crime: something’s amiss. In poems that take the part of felon and victim, detective and witness, judge and jury, the case becomes more puzzling and more ancient: what’s gone missing is not only an apple from the Garden, or fire from Olympus, or what Ophelia calls “the beauteous majesty of Denmark,” but nothing less than a world, a compendium of thefts over which all of us, thieves ourselves, keep watch.

Out of stock

The Nature Thief

Henry Walters writes with the whole of the English language on hand, and in his springing poems, sprung from Hamlet, sprung from experience, a marbled pebble is as eye-opening as a manuscript by Aeschylus. Bitterns plus automatic car washes plus Greek grammar plus fennec foxes plus the angels of the future–combined in the mind of Mr. Walters–equals a wingding of a book. These poems are occasions to rise to, exhilaratingly, and reading them I felt ‘the free carom of delight.’ There is no Henry Walters but Henry Walters, and English has never been fresher.

— Amy Leach

‘What’s more precise than precision? Illusion,’ wrote Marianne Moore. By illusion, I think she meant imagination, one like her own — slippery, cavorting, but also somehow revealing the deeper aspects of the natural world, other people, even herself. Whether walking in the woods or meeting a newborn, Henry Walters looks with precision at his surroundings. But in The Nature Thief, we revel even more in his rambunctious, reality-seeking imagination. ‘Each day I’m cracked wide open/ to let your risen body pass.’ Here is a poet who connects idiosyncrasies of ancient Greek grammar to our modern-day bee crisis, who knows that ‘precarious descends from sounds that meant to pray,’ who hears ‘hesitant start-of-the-rain-storm choliambs.’ I’ve experienced few recent pleasures like Walters’ unguarded complexities.

— Nate Klug

Recent death knells to the contrary, it appears the traditions of Western literature haven’t died an unceremonious death. Neither relic nor homage nor restoration, Henry Walters’ The Nature Thief gives proof to Faulkner’s famous adage: ‘The past is not dead, it is not even past.’ Poetry is a history of language, and Walters’ full-throated poems are pitched high and low, lyrical at one moment, street-wise the next, drawing on sources as various as a deconstructed Hamlet, a Greek grammar, the sound of a pool ball dropping into a leather pocket. Nothing is unlikely to find its way in, and nothing is unlikely to be burnished by the lyrical sway of this erudite and immensely talented poet.

— Sherod Santos

Henry Walters’s poetic vehicle is ignited by ingenuity, fueled by extravagance, and guided by form. His tradition is Joycean, and he too delights in eldritch diction and in wordplay gaudy (the ‘explosive ink’) and disguised (‘the rigor of mortise work’ and even ‘Give me light & a lift). Among other things an apiologist, he is himself a polylect, as well as a precise maximalist, a lyricist of science, a builder of breaches that bridge (‘a crack’s / a form of bond’), a mainstream eccentric.

— Stephen Yenser

Reviews of The Nature Thief

The Friday Poem (May 2023)

[A] provocative and highly original collection … [T]he voice of the poems is questing and uncertain, concerned with the gap between reality and perception; the surface of the language, its music and play, is intrinsic to the poems’ effects … [T]he poems in The Nature Thief are … challenging. There is a great deal of word play and allusion, and the trickery seems central to the poems’ designs … I’ve come away from The Nature Thief feeling less ignorant than I used to be, also invigorated by how much learning and ingenuity can be squeezed into a short lyric poem.

— Stephen Payne

To read the whole of this review, go to: https://thefridaypoem.com/the-nature-thief-by-henry-walters/

The Arts Fuse (December 12, 2022)

–Henry Walters likes to pretend his poems are difficult. They are not easy, but that does not mean they are difficult. They are just intelligent, and demand intelligence from a reader. They are musical, and call for a reader’s attentive ear. ‘It takes all kinds of in and outdoor schooling,’ Robert Frost cautioned, ‘To get accustomed to my kind of fooling.’ He could have been writing about Walters’s second book, The Nature Thief, with its ‘atoms aquiver in each flake, / & quarks in the atom / quaking, & infinitesimal strings / inside each quantum’ … Walters has enormous confidence in the artificiality of the verbal artifact to contain the ambiguities of the universe. If sometimes the erudition of his references leaves the reader feeling that the poet is speaking to a ghost nobody else can see (‘what a very singularly deep young man this deep young man must be’), the felt reality of the scene always asserts its sovereignty in a world of flesh and blood, with mortal consequences … Defying augury, and finding providence even in the fall of a grosbeak, Walters has presented his readers with a remarkable collection, resonant in content and — all the rarer these days — unique in voice. The poems here are cleaner and more focused than in his first book, Field Guide A Tempo, and lead us, as all good literature should do, after all the appearances and misdirections, feints and antic dispositions, to nothing but ourselves.

— Jim Kates

To read the whole of this review, go to: https://artsfuse.org/265914/poetry-review-henry-walters-the-nature-thief-memorable-verbal-acrobatics/

Two poems from Henry Walters’ The Nature Thief

Lullaby

Time’s continuous is what you’re taught.

Meanwhile a spider’s made traps of the irises.

The woods are full of these stories without plot.

I found a mushroom white as a dinner plate.

They say the edibles mimic the poisonous.

Time’s continual. Is what you’re taught

of any use at all? Somehow I forgot

the name of whatever’s doing in the honeybees.

The wards are full. This story has no plot:

new blights in the beeches, the ashes, the oaks. The rot

spreads night by night, whatever the disease.

Time’s contiguous is what. You’re taught

what your parents saw & spoke & thought

except they glossed (on purpose?) the pointlessness

the world’s so full of. Stories without plot

are what I want to hum when the light goes out

& the dark comes down between & over us.

Time discontinues, & all you’re taught

is words, words to the story we’re about.

Henry Walters

King of Infinite Space

Not two inches tall, a conquistador’s horse,

stepping as high through his terrarium

as any life-size bronze in monument.

Hock-deep in moss, fern-shaded, he restores

the Old-World grandeur he’s imported from.

He’s there for illusion’s sake, is what I meant,

to scale the proportions. Maybe his Spaniard knows

how small the jungle is, how low the dome,

how the air, the heat, the gargantuan sweating plants,

are toys under glass in someone else’s room.

The marvel of it is he’d care to claim

dominion in such a country, dominance,

staked to his bit of earth as if he were

the flag of his own unnature, in miniature.

Henry Walters

Excerpts

Two poems from Henry Walters' The Nature Thief

Lullaby

Time’s continuous is what you’re taught.

Meanwhile a spider’s made traps of the irises.

The woods are full of these stories without plot.

I found a mushroom white as a dinner plate.

They say the edibles mimic the poisonous.

Time’s continual. Is what you’re taught

of any use at all? Somehow I forgot

the name of whatever’s doing in the honeybees.

The wards are full. This story has no plot:

new blights in the beeches, the ashes, the oaks. The rot

spreads night by night, whatever the disease.

Time’s contiguous is what. You’re taught

what your parents saw & spoke & thought

except they glossed (on purpose?) the pointlessness

the world’s so full of. Stories without plot

are what I want to hum when the light goes out

& the dark comes down between & over us.

Time discontinues, & all you’re taught

is words, words to the story we’re about.

Henry Walters

King of Infinite Space

Not two inches tall, a conquistador’s horse,

stepping as high through his terrarium

as any life-size bronze in monument.

Hock-deep in moss, fern-shaded, he restores

the Old-World grandeur he’s imported from.

He’s there for illusion’s sake, is what I meant,

to scale the proportions. Maybe his Spaniard knows

how small the jungle is, how low the dome,

how the air, the heat, the gargantuan sweating plants,

are toys under glass in someone else’s room.

The marvel of it is he’d care to claim

dominion in such a country, dominance,

staked to his bit of earth as if he were

the flag of his own unnature, in miniature.

Henry Walters