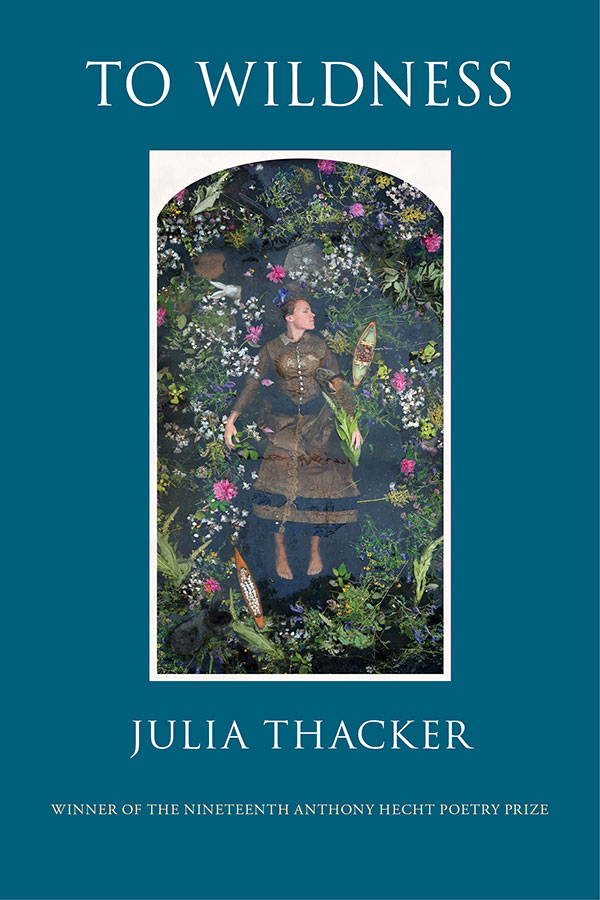

TO WILDNESS

Publication (US): March 11th, 2025

Publication (UK): May 6th, 2025

£10.99

Winner of the nineteenth Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize

Paul Muldoon, JudgeIn recipes, spells, odes and elegies, To Wildness conjures what has been lost and what remains. These are poems of the body. They rub up against one another and knock elbows. Plum Jam

calls preserving fruit as spiritual labor: To be elbow deep in a barrel/arms gloved crimson.

In this collection, the dead reside alongside the living. Ancestors roost in trees, having forgotten language, their coats inside out. Others sulk in the eaves, their ears clogged with clover.

The past made vivid renders an extravagant present and offers a balm to the isolation of the contemporary world.

Out of stock

TO WILDNESS

Teeming with image, sensation and sound, the poems in To Wildness tumble us into a glorious exuberance of catalog and character, rural landscape and dark imaginings (‘We ate ants peeled from bark, a rain of plums / when he rattled the trees. Lumbering. Shackled.’). Ancestral voices speak from the grave; fabulist figures like the girl buried with a finch tell their stories; and contemporary ghosts only the narrator sees abound (‘Let me touch them as they pass’). A southern gothic atmosphere hovers here: shapes twisting in the dark and the language to conjure them near. What a rich and thrilling collection!

— Joan Houlihan, It Isn’t a Ghost if it Lives in Your Chest

To Wildness is wildly alive—inventive and spunky and all over the map: from Bigfoot to Xanax to persimmons to Anna Karenina. In ‘When he said Sell a book, I heard Sail,’ the speaker confesses that she ‘wanted to hold the sky like a bowl, smudge the clouds. / Bring a sentence to its knees.’ That she does—and more!

— Ellen Doré Watson, pray me stay eager

Reviews of To Wildness

New Verse Review (March 2025)

In her self-assured debut collection To Wildness, Julia Thacker vividly brings to life the family and fast-vanishing Appalachian culture that formed her … Different losses suffuse the collection as the poet tries to grasp where she’s been. It’s a double loss, both of cultural identity and an American way of life. Maybe this hard way of life wasn’t meant to last; Thacker’s hardly nostalgic or sentimental. But loss is loss, it always hurts. In one poem (about a mental hospital) she asks: ‘But what am I in the world.’ Things around the poet seem to be de-materializing: ‘We don’t speak about the country of the old, / strolling unnoticed, dissolving / into sidewalks and salted air,’ An old fishing village is ‘gentrified’ in ‘Archeology’ —’I no longer recognize myself. / The way cod wrapped in brown / paper forgets the sea.’. In ‘Little Black Dress,’ ‘moths have made a feast’ of a dress that once slept on the beach. It’s not too great a leap to imagine this poet ‘setting fire’ to her past—America is, after all, a country of reinvention. So many of us set those fires, only to search for our identity in the ash. With To Wildness Julia Thacker celebrates the flames and the ash.

— Carla Sarett (To read the whole of this review, please go to New Verse Review.)

Two poems from Julia Thacker’s To Wildness

Braid Him into the Earth

Knee-high coffin of wicker, earth-boat floating through the woods.

Wrap him in heather, the old way. Hold a pocket mirror under his nose.

Say of him what we say of fathers.

If one of you has a three-string, then a tune.

Boots, stamp away spirits. If the ground is frozen,

dig shallow, spade ringing through ice, shale, mica-shine.

Lower the basket in a tangle of ginseng root, because I can’t.

Let well water seep into crevices, mineral, like nickels

on the tongue. Skin freckling in feldspar, beetle, slug.

If flood waters drift the body loose, let him not be found by a child.

Let bones wash up with clay pipes, beads, thumb-size skulls.

Let them whiten and scatter in blond fields.

Julia Thacker

God Denies Any Knowledge of Dead Angel in His Bed

He searches Heaven’s cabinets for a hangover cure.

Combs knotted stars from his beard.

Sets the morning agenda. To the blind shepherd

he dictates a note: The wind is blue.

And what of tsunamis, wars?

Macedonian wells infested with bees?

God has a headache. His hands tremble.

He cannot look at the heap of sheets,

her celestial body, marcelled bob, cold

in his chamber. No one understands

that he is full of duende. Not the swarm of angels,

their platinum regiment rapping

at his windows, rattling doors, voices sharp

and clear, Why? God covers his ears.

Julia Thacker

Excerpts

Two poems from Julia Thacker's To Wildness

Braid Him into the Earth

Knee-high coffin of wicker, earth-boat floating through the woods.

Wrap him in heather, the old way. Hold a pocket mirror under his nose.

Say of him what we say of fathers.

If one of you has a three-string, then a tune.

Boots, stamp away spirits. If the ground is frozen,

dig shallow, spade ringing through ice, shale, mica-shine.

Lower the basket in a tangle of ginseng root, because I can't.

Let well water seep into crevices, mineral, like nickels

on the tongue. Skin freckling in feldspar, beetle, slug.

If flood waters drift the body loose, let him not be found by a child.

Let bones wash up with clay pipes, beads, thumb-size skulls.

Let them whiten and scatter in blond fields.

Julia Thacker

God Denies Any Knowledge of Dead Angel in His Bed

He searches Heaven's cabinets for a hangover cure.

Combs knotted stars from his beard.

Sets the morning agenda. To the blind shepherd

he dictates a note: The wind is blue.

And what of tsunamis, wars?

Macedonian wells infested with bees?

God has a headache. His hands tremble.

He cannot look at the heap of sheets,

her celestial body, marcelled bob, cold

in his chamber. No one understands

that he is full of duende. Not the swarm of angels,

their platinum regiment rapping

at his windows, rattling doors, voices sharp

and clear, Why? God covers his ears.

Julia Thacker