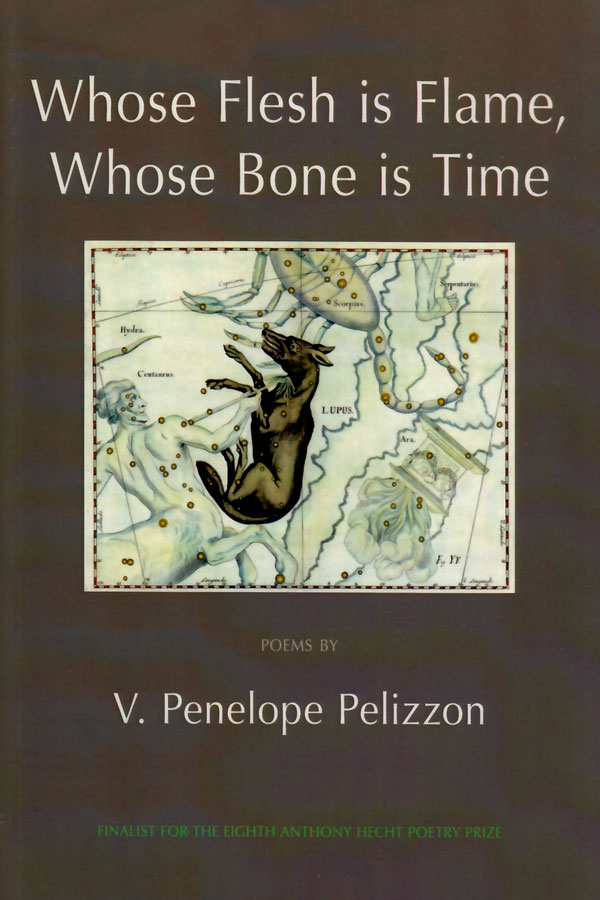

Whose Flesh is Flame, Whose Bone is Time

£8.99

Finalist for the 8th annual Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize

From the coal country of Western Pennsylvania, to Camorra-ridden Naples, to the streets of Damascus before the outbreak of civil war, the lyric poems in this outstanding collection chart the complexities of national and intimate identity. By turns playful, lamenting, sceptical, bawdy, and aggrieved, they find the human fingerprint below history's erasures, ultimately praising the endurance of the soul "so ample that, if that is all there is,/ she makes a feast of thorns."

Out of stock

Whose Flesh is Flame, Whose Bone is Time

Pelizzon’s poetry is acquiring a reputation. Her poems have appeared widely in periodicals (the Kenyon Review, Nation, Southern Review, and FIELD); her first book, Nostos, won the Hollis Summers Prize and the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America; she’s recently received a Lannan Foundation fellowship and an Amy Lowell traveling scholarship; and her second collection, Whose Flesh Is Flame, Whose Bone Is Time, was published in the spring of 2014. Her work, however, has not been the subject of detailed commentary, and the appearance of a particularly striking poem, ‘Nulla Dies Sine Linea’ in Whose Flesh Is Flame, presents an opportunity to rectify this deficiency and introduce her writing to a wider audience. Like much of her work, this poem is unshowy, nimble, personal, and expertly crafted. It is lightly constructed, yet the autumnal moment of insight it embodies has considerable emotional impact; it deftly mixes Apollonian reflection with the imagistic logic of dreams, and it is unself-consciously informal while drawing deep on traditional forms and techniques. Above all, its powers of implication and suggestion give rise to a series of harmonics or overtones that enrich the spare textures on the page.

– M. W. Rowe, Philosophy and Literature, 40:1, April 2016

To read the whole of this article, please click on Read Full Review

Reviews of Whose Flesh is Flame, Whose Stone is Time

Pleiades, 35.2, Summer 2015

"Pelizzon’s second full-length collection of poems, Whose Flesh Is Flame, Whose Bone Is Time, responds to many current questions regarding the construction of narrative and the ethos of lyric voice. This book does not, however, offer easy answers to the questions it raises. Pelizzon eschews familiar, ready-made channels of rhetoric and convention in favor of an exploration of the backwaters of memory and its sources. These poems avoid easy or predictable movements of mind. Ultimately, in their narratology and lyricism, Pelizzon’s poems blaze new trails. …

As we follow these rivers of narrative to their sources, the experience of reading Pelizzon’s poems becomes like travel across an unfamiliar landscape. Through travel, we confront mysteries-or sometimes, enact the alienation that we feel even as we hope, eventually, to return. In Whose Flesh Is Flame, Whose Bone Is Time, even ekphrastic poetry is an opportunity to travel away from the self and the known world. Pelizzon received an Amy Lowell Poetry Traveling Scholarship, and travel seems to have inspired many of the poems in this collection. Ultimately, as we navigate these rivers and their tributaries, the water sometimes catches fire when too laden with experience and suffering. Then, the poet’s potential for empathy gives rise to dazzling imagery. But Whose Flesh Is Flame, Whose Bone Is Time also suggests that poisoned rivers can run clean again." – Carol Quinn

The Hudson Review, Summer 2015

"In her second collection, V. Penelope Pelizzon tends to elegize places rather than persons and to write long poems, and poems in series, rather than terse lyrics…. [S]he references Ovid at key moments but emphasizes his experience of exile, a major theme of her book, over his myths of metamorphosis. As the wife of a diplomat, Pelizzon avoids the pitfalls common to contemporary ‘tourist’ poems; rather than indulge in pretty descriptions of foreign locales or preening meditations on works of art, Pelizzon contemplates the strangeness of living in an unfamiliar country. Her portrayal of Ovid in the dedicatory poem, ‘For Tony, compass,’ underscores the theme:

And from far Tomis one exile writing Joy to me is snow

Made soft by spring / And water on the pond instead of ice,

Hoping ships will dock and bring last winter’s

Letters from his wife. Heating himself a bowl of

Fermented mare’s milk. Reminding himself (twice)

Barbarus hic ego sum. Here, I am the barbarian.

Along with raising the question of who is exiled from whom (husband or wife), the motto suits Pelizzon’s speakers, who struggle to come to terms with being cultural outsiders and with the on-going shocks to selfimage that the experience demands. Pelizzon juxtaposes moments of cultural blindness and illumination, especially in her series of poems set in the Middle East, and in another long series, ‘The Monongahela Book of Hours,’ in which the speaker tries to adapt to Appalachia (a culture equally foreign to her sensibilities). Pelizzon also makes writing a primary theme, seeing language not in the tiresome, postmodern sense as purely self-referential, but as a flawed, yet seductive, means of communication woven into our DNA. Thus ‘The Ladder’ morphs into an analogue for language, writing, time, the architectural elegance of cells (beehive, monks’ cells, and of the human body), the musical staff, and the DNA spiral. Although Pelizzon’s long poems can be discursive, they build slowly, as she thinks through a problem from many angles and binds the whole together with recurring, interrelated metaphors, like the ladder, or like blood in the remarkable ‘Blood Memory,’ a meditation on menstruation, women’s reproductive freedom (or lack of it), and the consequences of bearing children. This method of thoughtful accretion of details that extends over many pages makes Pelizzon’s poetry difficult to quote in a review,because her effects are cumulative. As in an illuminated book—a form that inspires her approach—Pelizzon constructs her series from discrete poems teeming with descriptive details and sonically thickened with concrete, Anglo-Saxon-based diction. Like a new page in an illuminated book, each new poem shifts the scene, which enables Pelizzon to ground a series in a place yet also range over vast swathes of time. ‘The Monongahela Book of Hours’ incorporates not only the geographic and economic history of Appalachia, but also scenes from ancient Greece, Ovidian Rome, Medieval England, nineteenth-century England and Japan, and extends into geological time—the compaction of plants into coal becomes a metaphor for the changes in the region that result from the ravages of the coal industry. The metaphor also applies to Pelizzon’s layered approach to writing and the amount of time these complex poems must have taken to research and draft. Her first book, Nostos, appeared in 2000, and the poems in Whose Flesh is Flame, Whose Bone is Time bear the pressure of long incubation and intense thought." – Meg Schoerke

On my birthday

A crow guffaws, dirty man throwing the punch of his

One joke. And now, nearer, a murder

Answers, chortling from the pale hill’s brow.

From under my lashes’ wings they stretch

Clawed feet. There the unflappable years

Perch and stare. When I squint, when I

Grin, my new old face nearly hops

Off my old new face. Considering what’s flown,

What might yet fly, I lean my chin

On the palm where my half-cashed fortune lies.

The Waywiser Press

Fluency

Syria, 2009

Just returned from six months in the States,

Blinded by the burning screens of Google and Tweet

To body language on the street, I’m slow to understand the girl

Pointing at heaven, then at her ear and mouth,

Telling me God made her deaf and mute.

Shrewdly her bronze gaze appraises me.

I gesture at her stand and shrug. She flashes ten

Fingers, then ten again, showing what the lemons cost.

I nod. She bags a kilo, pinching her veil

Between her lips to cover her tattooed chin.

From my pocket I dredge a clutch of brassy coins.

Without taking her eyes off mine, she counts out twenty

Then shuts her hand quickly, making a cutting motion

Once to say halas, that’s enough.

Veil wrinkling in her teeth, she grins at me.

Before universities, before

Embassies, the souk. Some palm-smoothed truth,

Warmed in this back and forth, will outlast all the information

I’ve spent a half year circulating.

I weigh my words here, learning what they’re worth.

The Waywiser Press

Excerpts

Nulla Dies Sine Linea

On my birthday

A crow guffaws, dirty man throwing the punch of his

One joke. And now, nearer, a murder

Answers, chortling from the pale hill’s brow.

From under my lashes’ wings they stretch

Clawed feet. There the unflappable years

Perch and stare. When I squint, when I

Grin, my new old face nearly hops

Off my old new face. Considering what’s flown,

What might yet fly, I lean my chin

On the palm where my half-cashed fortune lies.

The Waywiser Press

Fluency

Syria, 2009

Just returned from six months in the States,

Blinded by the burning screens of Google and Tweet

To body language on the street, I’m slow to understand the girl

Pointing at heaven, then at her ear and mouth,

Telling me God made her deaf and mute.

Shrewdly her bronze gaze appraises me.

I gesture at her stand and shrug. She flashes ten

Fingers, then ten again, showing what the lemons cost.

I nod. She bags a kilo, pinching her veil

Between her lips to cover her tattooed chin.

From my pocket I dredge a clutch of brassy coins.

Without taking her eyes off mine, she counts out twenty

Then shuts her hand quickly, making a cutting motion

Once to say halas, that’s enough.

Veil wrinkling in her teeth, she grins at me.

Before universities, before

Embassies, the souk. Some palm-smoothed truth,

Warmed in this back and forth, will outlast all the information

I’ve spent a half year circulating.

I weigh my words here, learning what they’re worth.

The Waywiser Press