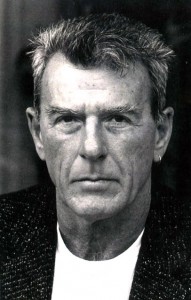

Thom Gunn

Thom Gunn was born in Gravesend, Kent, in August 1929, the elder son of Herbert and Ann Charlotte Gunn (née Thomson). His father was a successful journalist who, after many years spent working on provincial newspapers, moved to London, where he became editor, first of the Evening Standard, and then, somewhat later, of the Daily Sketch. Gunn’s mother had also been a journalist, but gave up her career with the births of Thom and his younger brother, Ander.

Thom Gunn was born in Gravesend, Kent, in August 1929, the elder son of Herbert and Ann Charlotte Gunn (née Thomson). His father was a successful journalist who, after many years spent working on provincial newspapers, moved to London, where he became editor, first of the Evening Standard, and then, somewhat later, of the Daily Sketch. Gunn’s mother had also been a journalist, but gave up her career with the births of Thom and his younger brother, Ander.

Gunn was only eight years old when the family moved to London, settling in Hampstead. He remembers the time and the place with great affection, and speaks of his boyhood as a very happy one. Just two years after the move, however, his parents were divorced. And four years after that, when Gunn was still in his mid-teens, his mother committed suicide. Asked about these events, and their effect on him, Gunn’s inclination has been to ask whether all adolescences aren’t unhappy, and to leave it at that.

Gunn’s love of reading seems to have been inspired by his mother, whose books filled the house. By the time of her death, he was immersed in the writings of Marlowe, Keats, Milton and Tennyson – to mention only the poets – and was unquestioningly committed to the idea ‘of books as not just a commentary on life but as a part of its continuing activity.’

After leaving school, Gunn did two years of National Service, and then went up to Cambridge. He was twenty-one, and by his own account – and notwithstanding his precocity as a reader – ‘strangely immature’. But, surrounded by lively and challenging contemporaries – Karl Miller, John Coleman, John Mander, Tony White, and Mark Boxer, amongst them – Gunn came of age, as can be seen from the poems he began to write at this time, poems which were to make up his first book.

Fighting Terms appeared in 1954, the year after Gunn’s graduation, to considerable acclaim. ‘This is one of the few volumes of postwar verse that all serious readers of poetry need to possess and to study,’ wrote the critic, John Press, and few dissented. As Timothy Steele put it more recently: ‘Impressive for their concentration, their vigour, and their effective fusion of traditional metre with contemporary idiom, these poems established [Gunn] as one of the most arresting voices of his generation.’

While an undergraduate, Gunn met Mike Kitay, an American. After leaving Cambridge, he followed Kitay to the United States, something made possible by the award of a creative writing fellowship at Stanford University, where he became a student of the poet and critic, Yvor Winters. Except for the occasional visit, and one year-long sojourn in the mid-’60s, Gunn was never to return to England. He had decided to make America his home, and in 1960 settled in San Francisco, the city where he has lived ever since.

Eight major collections have appeared since Fighting Terms – The Sense of Movement (1957), My Sad Captains (1961), Touch (1967), Moly (1971), Jack Straw’s Castle (1976), The Passages of Joy (1982), The Man with Night Sweats (1992), and, most recently, Boss Cupid (2000). Not all of them have been as enthusiastically received as that first book, however. Especially during the ‘70s and ‘80s, when he started to write out of his experiences as a user of soft and hard drugs, and to write more openly of his life as a homosexual, there were a number of critics who felt that he was squandering his talent, indulging in what one called ‘hippy silliness’, or abandoning himself to what another called ‘vacant counter-cultural slovenliness’.

With publication of The Man with Night Sweats, a collection which memorialized friends and acquaintances who had fallen victim to AIDS, those who had come to think of Gunn as a poet who had failed to live up to his early promise were obliged to reconsider. As Neil Powell, a long-standing but not uncritical admirer, put it: ‘In [the final section of the book] Gunn restores poetry to a centrality it has often seemed close to losing, by dealing in the context of a specific human catastrophe with the great themes of life and death, coherently, intelligently, memorably. One could hardly ask for more.’

Gunn has received a large number of awards and prizes for his work, amongst them the Levinson Prize (1955), the Somerset Maugham Award (1959), an Arts Council of Great Britain Award (1959), an American Institute of Arts and Letters Grant (1964), an American Academy Grant (1964), a Rockefeller Award (1966), a Guggenheim Fellowship (1971), the W.H. Smith Award (1980), the PEN (Los Angeles) Prize for Poetry (1983), the Sara Teasdale Prize (1988), the Los Angeles Times Kirsch Award (1988), the Lila Wallace/Reader’s Digest Writer’s Award (1990), the Forward Prize (1992), the Lenore Marshall Prize (1993), and a MacArthur Fellowship (1993).

– Philip Hoy, 2000

Thom Gunn died at his home in San Francisco on April 25th 2004