W.D. Snodgrass

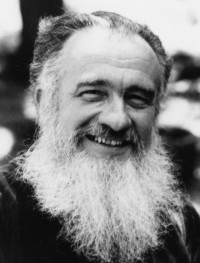

W.D. Snodgrass was born in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, in 1926, and was educated at Geneva College. His studies were interrupted when, during WWII, he was drafted into the Navy, and sent to the Pacific. After demobilization, Snodgrass resumed his studies, but transferred from Geneva College to the University of Iowa, eventually enrolling in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, which had been established in 1937, and was attracting as tutors some of the finest poetic talents of the day, amongst them John Berryman, Randall Jarrell and Robert Lowell. Snodgrass’s first poems appeared in 1951, and throughout the 1950’s he published in some of the most prestigious magazines (e.g. Botteghe Oscure, Partisan Review, the New Yorker, the Paris Review and the Hudson Review). However, in 1957, five sections from a sequence entitled ‘Heart’s Needle’ were included in Hall, Pack and Simpson’s anthology, New Poets of England and America, and these were to mark a turning-point. When Lowell had been shown early versions of these poems, in 1953, he had disliked them, but now he was full of admiration. He wrote to Elizabeth Bishop, saying: ‘I must tell you that I’ve discovered a new poet, W.D. Snodgrass – he was once one of my Iowa students, and I merely thought him about the best. Now he turns out to be better than anyone except Larkin.’He also wrote to Randall Jarrell, this time calling Snodgrass Larkin’s equal, and comparing him to the great French poet, Jules Laforgue. The point was developed in an interview he gave the Paris Review rather later:

‘I think a lot of the best poetry is [on the verge of being slight and sentimental]. Laforgue – it’s hard to think of a more delightful poet … Well, it’s on the verge of being sentimental, and if he hadn’t dared to be sentimental he wouldn’t have been a poet. I mean, his inspiration was that. There’s some way of distinguishing between false sentimentality, which is blowing up a subject and giving emotions that you don’t feel, and using whimsical, minute, tender, small emotions that most people don’t feel but which Laforgue and Snodgrass do. So that I’d say he [Snodgrass] had pathos and fragility … He has fragility along the edges and a main artery of power going through the center."

As well as writing to Bishop and Jarrell, Lowell wrote to Snodgrass, saying how much he admired the anthologized poems, and offering to help him find a book publisher. By the time Heart’s Needle was published, in 1959, Snodgrass had already won the The Hudson Review Fellowship in Poetry and an Ingram Merrill Foundation Poetry Prize. However, his first book brought him something more: a citation from the Poetry Society of America, a grant from the National Institute of Arts, and, most important of all, 1960’s Pulitzer Prize in Poetry. It is often said that Heart’s Needle inaugurated confessional verse. Snodgrass dislikes the term, and is quick to point out that the kind of verse he was writing at that time – a ‘searingly personal’ verse, as Ann Sexton called it – was hardly unprecedented. This is true, but it is also true that the genre he was reviving here seemed revolutionary to most of his contemporaries, reared as they had been on the anti-expressionistic principles of the New Critics. Snodgrass’s confessional work was to have a profound effect on many of his contemporaries, amongst them, and most importantly, Robert Lowell. The evidence for this is on display in Lowell’s most accomplished volume, Life Studies, which appeared in the same year as Heart’s Needle, and enabled its author to carry off the other great literary prize for 1960, the National Book Award. The effect on other poets, on both sides of the Atlantic, is fairly described as liberating. As one English critic was to put it later on:

”'Confessional' was an unfortunate way of describing what was new about Life Studies and Heart’s Needle – the term reeks of guilt and ingratiation – but it does recall the general surprise that such poetic vibrance and composure could be won from subjects that seemed doomed to privacy or narcissistic inflation."

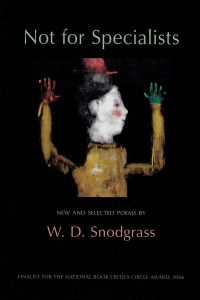

In the almost forty years since this auspicious debut, Snodgrass has gone on to produce an impressively diverse body of work, including After Experience, Remains, A Locked House, W.D.’s Midnight Carnival, The Death of Cock Robin, Each in His Season, The Führer Bunker, seven volumes of translations, and a large number of essays too, some of which were collected in In Radical Pursuit. These books have seriously divided the critics, bringing bouquets from some and brickbats from others. Most controversial of all was The Führer Bunker, a book which not only pitted critics against each other, but in one notable case pitted a critic against himself. Snodgrass has a long and distinguished academic career behind him, having taught at Cornell, Rochester, Wayne State, Syracuse, Old Dominion, and Delaware Universities. He retired from teaching in 1994, and now devotes himself full-time to his writing. He lives with his ‘fourth, last and best’ wife, the writer, Kathleen Snodgrass (née Browne), spending six months of each year at their home in New York, and the other six months in Mexico.

– Philip Hoy, 1998