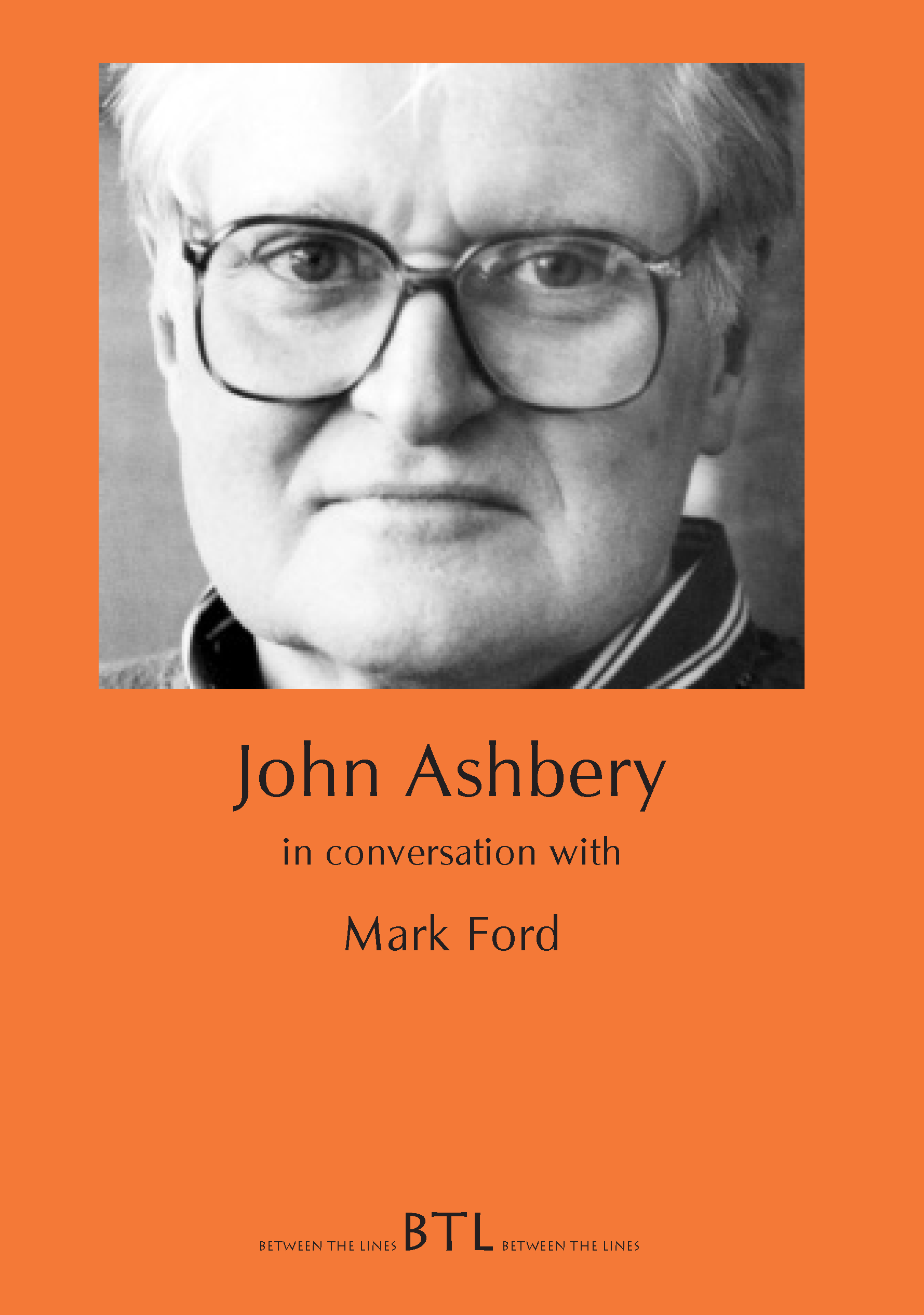

John Ashbery in Conversation with Mark Ford

£10.95

At 20,000 words, this is one of the longest and most candid interviews John Ashbery has ever given. As well as the interview, the volume contains a career sketch, the most far-reaching bibliography of works by and about Ashbery presently available, two uncollected poems, approximately 20 pages of hitherto unpublished photographs, and a representative range of quotations from the poet's critics and reviewers.

Between The Lines

“Essential reading for admirers of these poets … vigorous, illuminating and sometimes surprising adjuncts to the work itself.” — Neil Corcoran

“These books enrich our contextual understanding of contemporary poetry …” — Patrick Crotty, Times Literary Supplement

“A remarkably fine enterprise.” — Dana Gioia

“A splendid series.” — X.J. Kennedy

“Warmly recommended.” — Glyn Pursglove, Swansea Review

“These conversations are skilfully presented and offer sharp new perspectives on their subjects.” — N.S. Thompson, PN Review

Your latest long poem, Girls on the Run, is based on the eccentric, often quite disturbing pictures of Henry Darger. He’s another artist whose works are very much ‘home-made’.

The pure products of America go crazy!

What appealed to you about his peculiar saga of the Vivian Girls?

I don’t know exactly. I first saw his work in a museum in Lausanne, when I went to the university there to give a reading. I suppose it rang some distant chime because the little girls looked like the little girls I had crushes on when I was six or seven years old. The illustrations he used are all from that era. And it reminded me of the illustrated children’s books I had when I was very young. I don’t really like to think about the more gruesome aspects of his work.

I guess that should be left to the Chapman brothers.

Absolutely. Also, I was always fascinated by girls’ and women’s dresses; I liked them to have lots of pattern and ornament. When I was growing up, it was the era of Shirley Temple, and little girls tried to dress like her; they always had a row of smocking going across the top of the dress, which I found very attractive. I remember not liking women wearing solid-coloured dresses. My grandfather took me to his university once and introduced me to a secretary, who was wearing a rather ordinary frock. I complained to her, ‘You’re wearing a plain dress,’ meaning all one colour. ‘Well, yes, I suppose I am, laddie,’ she said, ‘now, run along.’

Wakefulness, which came out in 1998, includes a cento, “The Dong with the Luminous Nose”. Most of the lines come from nineteenth-century British poets – Hopkins, Tennyson, Coleridge, Edward Lear, Wordsworth, Arnold, Kipling, Keats, Housman, Blake, etc.

I keep forgetting where they all come from. I guess that poem’s a sort of tribute to the period when I used to read nineteenth-century poetry with a sense of awe that great poets could write great poems.

I seem to remember you once told an interviewer that you think of yourself as ‘John’ and of the voice of your poems as ‘Ashbery’. Could you explain the difference?

I don’t remember ever telling an interviewer that, though I don’t doubt that I said it, since it’s exactly the sort of stupid thing one says in interviews, this one being no exception.

How does a poem begin, and end, for you these days? I mean, is there anything in particular that prompts you to start – or urges you to stop?

How does a poem begin, and end, for me these days? Well, very much as it always has. A few words will filter in over the transom, as they say in publishing, and I’ll grab them and start trying to put them together. This causes something to happen to some other words that I hadn’t been thinking of which may well take over the poem to the point of excluding the original ones. What prompts me to start is a vague feeling that I ought to write a poem, and what ‘urges’ (rather too strong a word) me to stop is a sudden feeling that it would be pointless to continue. I’ve often described this as a kind of timer that goes off to tell me the poem is done and I must remove it from the oven. If I try to go on and write some more, it turns out to be a fiasco – ‘flatter than a bride’s soufflé’, as I insensitively put it many years ago in my play, The Compromise.

Your recent books in particular are extremely diverse in terms of the forms they use: the pantoum of “Hotel Lautréamont”, the rhyming quatrains of “Tuesday Evening”, the Robert Walser-style prose poems. Is there a form you’d like to try your hand at, but haven’t so far?

Well, you know I tried recently to write several villanelles, but I don’t think any of them worked out. There was one I was maybe going to use in a collection, but then I finally axed it. I was rereading William Empson’s poetry, which I like a lot, and of course he wrote several very successful villanelles. ‘They bled an old dog dry …’

The Waywiser Press

Mark Ford was born in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1962. He went to school in London, and attended Oxford and Harvard Universities. He wrote his doctorate at Oxford University on the poetry of John Ashbery, and has published widely on nineteenth- and twentieth-century American writing. From 1991-1993 he was Visiting Lecturer at Kyoto University in Japan. He currently teaches in the English Department at University College London, where he is a Senior Lecturer.

Ford has published two collections of poetry, Landlocked (Chatto & Windus, 1992;1998) and Soft Sift (Faber & Faber, 2001/Harcourt Brace, 2003), and has also written a critical biography of the French poet, playwright and novelist, Raymond Roussel, Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams (Faber & Faber, 2000/Cornell University Press, 2001). A Driftwood Altar, a collection of his essays and reviews, was published by The Waywiser Press in 2005.

He is a regular contributor to the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books and the New York Review of Books, amongst other journals.

John Lawrence Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York, on July 28th 1927, the first son of Chester Frederick (a farmer) and Helen Ashbery (a biology teacher). He went to school in Rochester and in his home town of Sodus, and at the age of sixteen was sent as a boarder to Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. After graduating from there, in 1945, he entered Harvard University, where he studied English.

John Lawrence Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York, on July 28th 1927, the first son of Chester Frederick (a farmer) and Helen Ashbery (a biology teacher). He went to school in Rochester and in his home town of Sodus, and at the age of sixteen was sent as a boarder to Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. After graduating from there, in 1945, he entered Harvard University, where he studied English.

Ashbery had been writing poetry since his schooldays, and while at Deerfield had even had two of his poems accepted by the prestigious magazine, Poetry. Two years after he went to college he submitted work to The Harvard Advocate, the recently revived undergraduate magazine, whose editors were Robert Bly, Donald Hall and Kenneth Koch. The poems were quickly published, and just a few months later their author found himself installed as the fourth member of the magazine’s editorial board. According to Hall, he rapidly became the Advocate’s leading light.

Ashbery obtained his BA in 1949, and went to Columbia University to study for his MA. He graduated from there in 1951, and found work in publishing, becoming a copywriter, first for Oxford University Press and then for the McGraw Hill Book Company. Poems of his continued to appear in magazines, amongst them Furioso, Poetry New York and Partisan Review, but as well as pursuing his literary interests, Ashbery was now mixing in New York’s artistic circles, frequenting the galleries, and getting to know the painters. Then, in 1953, thanks to its director, John Myers, the city’s influential Tibor de Nagy Gallery published a slender chapbook of Ashbery’s poems, complete with illustrations by the artist Jane Freilicher. Turandot and Other Poems seems not to have attracted much notice, but Alfred Corn subsequently included its publication in a list of the most important events ‘in the history of twentieth century avant-garde art’.

Three years later, by which time he was in Paris on a Fulbright fellowship, Ashbery’s first full collection was chosen by W.H. Auden for inclusion in Yale University Press’s Younger Poets Series. Reviewing Some Trees for Poetry, Frank O’Hara wrote of Ashbery’s ‘faultless music’ and ‘originality of perception’, and pronounced it ‘the most beautiful first book to appear in America since Harmonium’. Not everyone felt so enthusiastic, however. William Arrowsmith, writing for The Hudson Review, declared that he had ‘no idea most of the time what Mr Ashbery is talking about … beyond the communication of an intolerable vagueness that looks as if it was meant for precision,’ and added, for good measure: ‘What does come through is an impression of an impossibly fractured brittle world, depersonalized and discontinuous, whose characteristic emotional gesture is an effete and cerebral whimsy.’

Ashbery’s period as a Fulbright fellow came to an end in 1957, but life in Paris had been so much to his liking that, after another year in the US – a year in which he took graduate classes at New York University and worked as an instructor in elementary French – he returned, avowedly to pursue research for a doctoral dissertation on the writer Raymond Roussel. He was to remain in France for several years, supporting himself by writing for a number of different journals. He had started to review for the magazine ArtNews during his year in New York, and continued with this once back in Paris. Then, in 1960, he became art critic for the New York Herald Tribune (international edition), and, in 1961, art critic for Art International as well. Nor were these his only such commitments. In the same year that he started writing for the New York Herald Tribune, he joined with Kenneth Koch, Harry Mathews, and James Schuyler and founded the literary magazine, Locus Solus. That folded in 1962, but the following year he got together with Anne Dunn, Rodrigo Moynihan and Sonia Orwell, and founded Art and Literature, a quarterly review he worked on until he went back to living in the US, in 1966.

When not writing reviews, or engaged in editorial work, Ashbery still found time to write poetry. It was poetry of a very different kind to that he had published in Some Trees, however, and readers familiar with the first book will have been altogether unprepared for the ‘violently experimental’ character of the second (unless they had been keeping an eye on Big Table and Locus Solus, the magazines in which some of these poems first appeared). Reactions to The Tennis Court Oath were generally hostile. James Schevill told readers of the Saturday Review: ‘The trouble with Ashbery’s work is that he is influenced by modern painting to the point where he tries to apply words to the page as if they were abstract, emotional colors and shapes … Consequently, his work loses coherence … There is little substance to the poems in this book.’ And Mona Van Duyn told readers of Poetry: ‘If a state of continuous exasperation, a continuous frustration of expectation, a continuous titillation of the imagination are sufficient response to a series of thirty-one poems, then these have been successful. But to be satisfied with such a response I must change my notion of poetry.’ Even so devoted an admirer of Ashbery as Harold Bloom thought the book a ‘fearful disaster’ and confessed to being baffled at how its author could have ‘collapse[d] into such a bog’ just six years after Some Trees.

Ashbery has said that when he was working on the poems that went into The Tennis Court Oath he was ‘taking language apart so I could look at the pieces that made it up’, and that after he’d done this he was intent on ‘putting [the pieces] back together again’. Rivers and Mountains, published in the year that he settled back in the US, was the first of his books to follow, and marked what several of his critics regard as his real arrival as a poet, with poems such as “These Lacustrine Cities”, “Clepsydra” and “The Skaters” all demonstrating for the first time what one of them has called the ‘astonishing range and flexibility of Ashbery’s voice’. The volume was nominated for the National Book Award.

Ashbery had gone back to the US after being offered the job of executive editor of ArtNews. Four years later, in 1969, the Black Sparrow Press published his long poem “Fragment”, with illustrations by the painter Alex Katz. Writing about this seven years on, Bloom declared that it was, for him, Ashbery’s ‘finest work’. By then, it should be noted, the poem had plenty of rivals, since The Double Dream of Spring (which included “Fragment”) had appeared in 1970, Three Poems had appeared in 1972, and The Vermont Notebook and Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror had appeared in 1975. All of these books had won Ashbery admiring notices, and Three Poems had also secured him the Modern Poetry Association’s Frank O’Hara Prize, but it was Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror that proved to be the breakthrough, carrying off all three of America’s most important literary prizes – the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. John Malcolm Brinnin’s notice for the New York Times Book Review can be taken as representative: ‘[A] collection of poems of breathtaking freshness and adventure in which dazzling orchestrations of language open up whole areas of consciousness no other American poet has even begun to explore …‘

ArtNews was sold in 1972, and Ashbery had to find himself another job. A Guggenheim Fellowship sustained him for some months, but then, in 1974, he took up the offer of a teaching post at Brooklyn College – a part of the City University of New York – where he co-directed the MFA program in creative writing. Though he has confessed to not liking teaching very much, he has been doing it ever since (with one extended break between 1985 and 1990, made possible by the award of a MacArthur Foundation fellowship). He left Brooklyn College in 1990, was Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard between 1989 and 1990, and from then until now has been Charles P. Stevenson, Jr. Professor of Languages and Literature at Bard College at Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Just as Ashbery’s art reviewing and editorial work seemed not to affect his creative output during the Sixties and early Seventies, so his teaching work seems not to have affected it during the decades since. In fact, he has been remarkably prolific, averaging a new collection once every eighteen months. Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror was followed by: Houseboat Days (1977), As We Know (1979), Shadow Train (1981), A Wave (1984), April Galleons (1987), Flow Chart (1991), Hotel Lautréamont (1992), And the Stars Were Shining (1994), Can You Hear, Bird (1995), Wakefulness (1998), Girls on the Run (1999), Your Name Here (2000), As Umbrellas Follow Rain (2001) and Chinese Whispers (2002) (to mention only his book-length collections). He has also published Three Plays (1978), Reported Sightings (a selection of his art reviews) (1989) and Other Traditions (revised versions of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures he gave in 1989 and 1990).

This large body of work has won Ashbery numerous admirers, amongst them some of today’s most prominent critics. It has also won him numerous honours, awards and prizes, a partial list of which would include (apart from those already mentioned) two Ingram Merrill Foundation grants (1962, 1972), Poetry magazine’s Harriet Monroe Poetry Award (1963) and Union League Civic and Arts Foundation Prize (1966), two Guggenheim fellowships (1967, 1973), two National Endowment for the Arts publication awards (1969, 1970), the Poetry Society of America’s Shelley Memorial Award (1973), Poetry magazine’s Levinson Prize (1977), a National Endowment for the Arts Composer/Librettist grant (with Elliott Carter) (1978), a Rockefeller Foundation grant for playwriting (1979-1980), the English Speaking Union Award (1979), membership of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (1980), fellowship of the Academy of American Poets (1982), the New York City Mayor’s Award of Honour for Arts and Culture, Bard College’s Charles Flint Kellogg Award in Art and Letters, membership of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1983), American Poetry Review’s Jerome J. Shestack Poetry Award (1983, 1995), Nation magazine’s Lenore Marshall Award, the Bollingen Prize, Timothy Dwight College/Yale University’s Wallace Stevens fellowship (1985), the MLA Common Wealth Award in Literature (1986), the American Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award (1987), Chancellorship of the Academy of American Poets (1988-1989), Brandeis University’s Creative Arts Award in Poetry (Medal) (1989), the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts (Munich)’s Horst Bienek Prize for Poetry (1991), Poetry magazine’s Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Academia Nazionale dei Lincei (Rome)’s Antonio Feltrinelli International Prize for Poetry (1992), the French Ministry of Education and Culture (Paris)’s Chevalier de L’Ordre des Arts et Lettres (1993), the Poetry Society of America’s Robert Frost Medal (1995), the Grand Prix des Biennales Internationales de Poésie (Brussels), the Silver Medal of the City of Paris (1996), the American Academy of Arts and Letters’s Gold Medal for Poetry (1997), Boston Review of Books’s Bingham Poetry Prize (1998), the State of New York/New York State Writers Institute’s Walt Whitman Citation of Merit (2000), Columbia County (New York) Council on the Arts Special Citation for Literature, the Academy of American Poets’s Wallace Stevens Award, Harvard University’s Signet Society Medal for Achievement in the Arts (2001), the New York State Poet Laureateship (2001-2002), and France’s Officier de la Légion d’Honneur (2002).

Ashbery lives in the Chelsea district of New York City and in Hudson, New York.