Thom Gunn in Conversation with James Campbell

£9.50

A 112 page volume, containing an extended interview, first broadcast on the BBC, a career sketch, an updated version of Hagstrom and Bixby’s comprehensive 1979 bibliography, several pages of quotations from Gunn’s critics and reviewers, and the poem,“Clean Clothes: A Soldier’s Song”.

Out of stock

Between The Lines

“This volume gives us an informative, friendly 42 page Q A between Gunn and critic, biographer, and TLS eminence James Campbell, conducted in January 1999, after Gunn had completed what’s his new book, Boss Cupid … As usual, Gunn comes across as admirable: reserved about his private life, thoughtful about his principles. He’s someone who’s quite devoted to nightlife, to sex of course, to fun, and yet he’s articulated a liveable moral stringency, and an entirely appealing way of connecting art to ethical choice … It’s dangerous to take anyone’s life as exemplary – that must be one of the differences between people and poems – but Gunn’s in some ways can seem so.” ‒ Stephen Burt, Poetry Review (Summer 2000),

“Thom Gunn … appears as sunny as the California in which he has lived for almost five decades. He speaks with matter-of-fact ease about his literary acquaintances in England and America, the depredations of AIDS as commemorated in The Man with Night Sweats, and the drug-taking and sexual abandon of pre-AIDS California. Although he agrees with James Campbell that his typification of Gary Snyder as someone who ‘writes poetry, and like most serious poets is concerned at finding himself on a barely known planet, in an almost unknown universe, where he must attempt to create and discover meanings’ is really a self-description, he emerges from his interview as a distinctly cooler person than that – engaging and intelligent, certainly, but not given to thinking in planetary or metaphysical terms … Campbell is a skilful interviewer, in whom his subject has evident confidence.” ‒ Patrick Crotty, TLS (October 27, 2000)

When did you move to California?

In 1954. I crossed the Atlantic on the Queen Mary. The middle day of the three-day journey was my twenty-fifth birthday. I eventually crossed the country by train, getting off in Oakland, and arriving in San Francisco by ferry, which is a wonderful way of entering the city, a spectacular way of entering it. I came for one year, but I stayed on for – well, what would it be? – forty-five years or so.

What was behind the move to California? Was it just the offer of the fellowship?

I came to California for two reasons: to study with Yvor Winters at Stanford, but primarily to be in the same country as Mike, who’d had to go into the air-force for a couple of years, doing the equivalent of our National Service. Even though he was down in Texas, at least I was in the same country as him, and I could visit him, and him me.

You didn’t start living in San Francisco right away, did you?

No, after Stanford I went down to San Antonio for a year, and taught at a small Presbyterian university called Trinity. It was the first teaching I’d ever done, and I was a really terrible teacher, didn’t know anything about it. The football players who were in my freshman English class were very amused by me, and I was very amused by them, so we all got on well. But that was a year of considerable tedium, and dust storms, and other Texan things like that.

You began to write the poems included in The Sense of Movement, some of which have very up-to-date American subject-matter – I’m thinking of ‘On The Move’ and ‘Elvis Presley’, in particular – but not yet an American tone.

No. It’s hilarious actually. I thought of doing a series of poems, based on Marvell’s mower poems, about the motor cyclist. This was the year after Marlon Brando’s The Wild One, and the myth was just starting up. I only wrote two. One was called ‘On The Move’ and the other was called ‘The Unsettled Motorcyclist’s Vision of his Death’. There are many things to dislike about ‘On the Move’. To begin with, there’s the constant use of the word ‘one’, which I find very stilted now. Now I would use the word ‘you’ rather than ‘one’. Then again, it’s such a period piece. I say that, not because it’s based on a short book by Sartre, or because it’s also based on The Wild One, but because of its tremendous formality, which I really dislike. I’m also not sure that the last line means anything: ‘One is always nearer by not keeping still.’ Nearer what? Well, yes, the motorcyclist is nearer the destination, but what’s the destination of human beings? Aha! It’s a question that seems to answer itself but doesn’t.

Yes, I was going to ask you about the line, ‘It is a part solution, after all.’ A part solution to what?

I don’t know. There’s another reason for saying that there’s something wrong with the poem. It’s unnecessarily well-known and anthologized.

That must be because of its subject-matter, motor-cyclists.

Yes, as though the industrial revolution had never provided subject-matter for poetry before. The other poem you mentioned was ‘Elvis Presley’. He hadn’t been around for long when that was first published, in 1957. He’d only been going about two years. There’s only one good line in the poem, which was used by George Melly for the title of his book, Revolt into Style. You have to remember that that poem is about the young Elvis Presley, the Presley of ‘Hound Dog’ and ‘Heartbreak Hotel’:

Whether he poses or is real, no cat

Bothers to say: the pose held is a stance,

Which, generation of the very chance

It wars on, may be posture for combat.

And you might ask, ‘Combat against what?’

The subject of The Sense of Movement is the will, and you’ve said about yourself at that time that you were ‘a Shakespearian, Sartrean Fascist’.

Well, I have to make a confession to you. I didn’t know, what I later learned, that ‘will’ in Shakespeare refers to the penis, or more generally to the sexual organs of either sex. I’d got a degree from Cambridge without ever having been informed of this fact. None of the editions of the sonnets that I used told me this. I couldn’t have known it, and I don’t think any of my friends knew it either, though, like a lot of people at university, I learned more from my friends than I did from my teachers. I think I was unconsciously using it for that, though, don’t you? It was very much a male kind of will, a penis-like will.

Is it true to say that while the main influence on Fighting Terms was Leavis, the main influence on The Sense of Movement was Winters?

What’s interesting about this is that poets aren’t supposed to be influenced by critics. People used to say of Leavis that he never influenced poetry, but that’s not true. He did influence my poetry. Of course, he didn’t like contemporary poetry much, and if he ever read my poetry – I don’t know if he did, but he might have – I shouldn’t think he liked it. But Leavis and Winters were important to me, mainly because of their technical remarks. It was a wonderful thing to hear Leavis talking about the speech in Macbeth that goes, ‘If it were done, when ‘tis done, then ‘twere well / It were done quickly,’ commenting on the pauses and the plunges forward at the ends of the lines. He was very good when speaking about the relationship between verse movement and feeling. I didn’t know anything about that kind of thing when I went up to Cambridge, so it was terrific learning about it.

As to Winters, well, of course, he was not only a teacher and critic, like Leavis, but a poet as well. He was a formidable personality – a bit too formidable at first. But eventually I realized there was a lot to be learned from him. He was much less rigid in conversation than he seems to be in his critical writings. One of the first things he said was, ‘What, you haven’t read William Carlos Williams or Wallace Stevens!? You should read them at once.’ He regarded that as an essential part of my education. And of course he was right. These people’s work had not been available to me in England, except maybe in anthologies. I fought Winters a lot at first. I mean, I quarrelled with him and disagreed with him. He kind of liked that. I said once, writing about him, that I felt like the rebellious soldier in the sergeant’s platoon in one of those Hollywood war movies. He liked me in grim sort of way because I opposed him. I didn’t really oppose him that much. I did argue with him, though. At the end of the first year, I wrote a poem called ‘To Yvor Winters, 1955’, and perhaps the last section of it says more about the relationship than the words I’ve used here. I was accused of imitating Winters’s style in writing this poem, and I was: it was part of a tribute to him:

Though night is always close, complete negation

Ready to drop on wisdom and emotion,

Night from the air or the carnivorous breath,

Still it is right to know the force of death,

And, as you do, persistent, tough in will,

Raise from the excellent the better still.

The Waywiser Press

James Campbell was born in Glasgow and educated at Edinburgh Uni-versity. Between 1978 and 1982, he was the editor of the New Edinburgh Review. He is the author of several books of non-fiction, including Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin (1991); Paris Interzone: Richard Wright, Lolita, Boris Vian and Others on the Left Bank (1994); and This Is the Beat Generation (1999). In addition, he has edited the Picador Book of Blues and Jazz, and written a play, The Midnight Hour, which has been performed in the United States and France. He lives in London, where he works for the Times Literary Supplement.

James Campbell was born in Glasgow and educated at Edinburgh Uni-versity. Between 1978 and 1982, he was the editor of the New Edinburgh Review. He is the author of several books of non-fiction, including Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin (1991); Paris Interzone: Richard Wright, Lolita, Boris Vian and Others on the Left Bank (1994); and This Is the Beat Generation (1999). In addition, he has edited the Picador Book of Blues and Jazz, and written a play, The Midnight Hour, which has been performed in the United States and France. He lives in London, where he works for the Times Literary Supplement.

Thom Gunn was born in Gravesend, Kent, in August 1929, the elder son of Herbert and Ann Charlotte Gunn (née Thomson). His father was a successful journalist who, after many years spent working on provincial newspapers, moved to London, where he became editor, first of the Evening Standard, and then, somewhat later, of the Daily Sketch. Gunn’s mother had also been a journalist, but gave up her career with the births of Thom and his younger brother, Ander.

Gunn was only eight years old when the family moved to London, settling in Hampstead. He remembers the time and the place with great affection, and speaks of his boyhood as a very happy one. Just two years after the move, however, his parents were divorced. And four years after that, when Gunn was still in his mid-teens, his mother committed suicide. Asked about these events, and their effect on him, Gunn’s inclination has been to ask whether all adolescences aren’t unhappy, and to leave it at that.

Gunn’s love of reading seems to have been inspired by his mother, whose books filled the house. By the time of her death, he was immersed in the writings of Marlowe, Keats, Milton and Tennyson – to mention only the poets – and was unquestioningly committed to the idea ‘of books as not just a commentary on life but as a part of its continuing activity.’

After leaving school, Gunn did two years of National Service, and then went up to Cambridge. He was twenty-one, and by his own account – and notwithstanding his precocity as a reader – ‘strangely immature’. But, surrounded by lively and challenging contemporaries – Karl Miller, John Coleman, John Mander, Tony White, and Mark Boxer, amongst them – Gunn came of age, as can be seen from the poems he began to write at this time, poems which were to make up his first book.

Fighting Terms appeared in 1954, the year after Gunn’s graduation, to considerable acclaim. ‘This is one of the few volumes of postwar verse that all serious readers of poetry need to possess and to study,’ wrote the critic, John Press, and few dissented. As Timothy Steele put it more recently: ‘Impressive for their concentration, their vigour, and their effective fusion of traditional metre with contemporary idiom, these poems established [Gunn] as one of the most arresting voices of his generation.’

While an undergraduate, Gunn met Mike Kitay, an American. After leaving Cambridge, he followed Kitay to the United States, something made possible by the award of a creative writing fellowship at Stanford University, where he became a student of the poet and critic, Yvor Winters. Except for the occasional visit, and one year-long sojourn in the mid-’60s, Gunn was never to return to England. He had decided to make America his home, and in 1960 settled in San Francisco, the city where he has lived ever since.

Eight major collections have appeared since Fighting Terms – The Sense of Movement (1957), My Sad Captains (1961), Touch (1967), Moly (1971), Jack Straw’s Castle (1976), The Passages of Joy (1982), The Man with Night Sweats (1992), and, most recently, Boss Cupid (2000). Not all of them have been as enthusiastically received as that first book, however. Especially during the ‘70s and ‘80s, when he started to write out of his experiences as a user of soft and hard drugs, and to write more openly of his life as a homosexual, there were a number of critics who felt that he was squandering his talent, indulging in what one called ‘hippy silliness’, or abandoning himself to what another called ‘vacant counter-cultural slovenliness’.

With publication of The Man with Night Sweats, a collection which memorialized friends and acquaintances who had fallen victim to AIDS, those who had come to think of Gunn as a poet who had failed to live up to his early promise were obliged to reconsider. As Neil Powell, a long-standing but not uncritical admirer, put it: ‘In [the final section of the book] Gunn restores poetry to a centrality it has often seemed close to losing, by dealing in the context of a specific human catastrophe with the great themes of life and death, coherently, intelligently, memorably. One could hardly ask for more.’

Gunn has received a large number of awards and prizes for his work, amongst them the Levinson Prize (1955), the Somerset Maugham Award (1959), an Arts Council of Great Britain Award (1959), an American Institute of Arts and Letters Grant (1964), an American Academy Grant (1964), a Rockefeller Award (1966), a Guggenheim Fellowship (1971), the W.H. Smith Award (1980), the PEN (Los Angeles) Prize for Poetry (1983), the Sara Teasdale Prize (1988), the Los Angeles Times Kirsch Award (1988), the Lila Wallace/Reader’s Digest Writer’s Award (1990), the Forward Prize (1992), the Lenore Marshall Prize (1993), and a MacArthur Fellowship (1993).

– Philip Hoy, 2000

Thom Gunn died at his home in San Francisco on April 25th 2004

Excerpts

When did you move to California?

In 1954. I crossed the Atlantic on the Queen Mary. The middle day of the three-day journey was my twenty-fifth birthday. I eventually crossed the country by train, getting off in Oakland, and arriving in San Francisco by ferry, which is a wonderful way of entering the city, a spectacular way of entering it. I came for one year, but I stayed on for – well, what would it be? – forty-five years or so.

What was behind the move to California? Was it just the offer of the fellowship?

I came to California for two reasons: to study with Yvor Winters at Stanford, but primarily to be in the same country as Mike, who’d had to go into the air-force for a couple of years, doing the equivalent of our National Service. Even though he was down in Texas, at least I was in the same country as him, and I could visit him, and him me.

You didn’t start living in San Francisco right away, did you?

No, after Stanford I went down to San Antonio for a year, and taught at a small Presbyterian university called Trinity. It was the first teaching I’d ever done, and I was a really terrible teacher, didn’t know anything about it. The football players who were in my freshman English class were very amused by me, and I was very amused by them, so we all got on well. But that was a year of considerable tedium, and dust storms, and other Texan things like that.

You began to write the poems included in The Sense of Movement, some of which have very up-to-date American subject-matter – I’m thinking of ‘On The Move’ and ‘Elvis Presley’, in particular – but not yet an American tone.

No. It’s hilarious actually. I thought of doing a series of poems, based on Marvell’s mower poems, about the motor cyclist. This was the year after Marlon Brando’s The Wild One, and the myth was just starting up. I only wrote two. One was called ‘On The Move’ and the other was called ‘The Unsettled Motorcyclist’s Vision of his Death’. There are many things to dislike about ‘On the Move’. To begin with, there’s the constant use of the word ‘one’, which I find very stilted now. Now I would use the word ‘you’ rather than ‘one’. Then again, it’s such a period piece. I say that, not because it’s based on a short book by Sartre, or because it’s also based on The Wild One, but because of its tremendous formality, which I really dislike. I’m also not sure that the last line means anything: ‘One is always nearer by not keeping still.’ Nearer what? Well, yes, the motorcyclist is nearer the destination, but what’s the destination of human beings? Aha! It’s a question that seems to answer itself but doesn’t.

Yes, I was going to ask you about the line, ‘It is a part solution, after all.’ A part solution to what?

I don’t know. There’s another reason for saying that there’s something wrong with the poem. It’s unnecessarily well-known and anthologized.

That must be because of its subject-matter, motor-cyclists.

Yes, as though the industrial revolution had never provided subject-matter for poetry before. The other poem you mentioned was ‘Elvis Presley’. He hadn’t been around for long when that was first published, in 1957. He’d only been going about two years. There’s only one good line in the poem, which was used by George Melly for the title of his book, Revolt into Style. You have to remember that that poem is about the young Elvis Presley, the Presley of ‘Hound Dog’ and ‘Heartbreak Hotel’:

Whether he poses or is real, no cat

Bothers to say: the pose held is a stance,

Which, generation of the very chance

It wars on, may be posture for combat.

And you might ask, ‘Combat against what?’

The subject of The Sense of Movement is the will, and you’ve said about yourself at that time that you were ‘a Shakespearian, Sartrean Fascist’.

Well, I have to make a confession to you. I didn’t know, what I later learned, that ‘will’ in Shakespeare refers to the penis, or more generally to the sexual organs of either sex. I’d got a degree from Cambridge without ever having been informed of this fact. None of the editions of the sonnets that I used told me this. I couldn’t have known it, and I don’t think any of my friends knew it either, though, like a lot of people at university, I learned more from my friends than I did from my teachers. I think I was unconsciously using it for that, though, don’t you? It was very much a male kind of will, a penis-like will.

Is it true to say that while the main influence on Fighting Terms was Leavis, the main influence on The Sense of Movement was Winters?

What’s interesting about this is that poets aren’t supposed to be influenced by critics. People used to say of Leavis that he never influenced poetry, but that’s not true. He did influence my poetry. Of course, he didn’t like contemporary poetry much, and if he ever read my poetry – I don’t know if he did, but he might have – I shouldn’t think he liked it. But Leavis and Winters were important to me, mainly because of their technical remarks. It was a wonderful thing to hear Leavis talking about the speech in Macbeth that goes, ‘If it were done, when ‘tis done, then ‘twere well / It were done quickly,’ commenting on the pauses and the plunges forward at the ends of the lines. He was very good when speaking about the relationship between verse movement and feeling. I didn’t know anything about that kind of thing when I went up to Cambridge, so it was terrific learning about it.

As to Winters, well, of course, he was not only a teacher and critic, like Leavis, but a poet as well. He was a formidable personality – a bit too formidable at first. But eventually I realized there was a lot to be learned from him. He was much less rigid in conversation than he seems to be in his critical writings. One of the first things he said was, ‘What, you haven’t read William Carlos Williams or Wallace Stevens!? You should read them at once.’ He regarded that as an essential part of my education. And of course he was right. These people’s work had not been available to me in England, except maybe in anthologies. I fought Winters a lot at first. I mean, I quarrelled with him and disagreed with him. He kind of liked that. I said once, writing about him, that I felt like the rebellious soldier in the sergeant’s platoon in one of those Hollywood war movies. He liked me in grim sort of way because I opposed him. I didn’t really oppose him that much. I did argue with him, though. At the end of the first year, I wrote a poem called ‘To Yvor Winters, 1955’, and perhaps the last section of it says more about the relationship than the words I’ve used here. I was accused of imitating Winters’s style in writing this poem, and I was: it was part of a tribute to him:

Though night is always close, complete negation

Ready to drop on wisdom and emotion,

Night from the air or the carnivorous breath,

Still it is right to know the force of death,

And, as you do, persistent, tough in will,

Raise from the excellent the better still.

The Waywiser Press

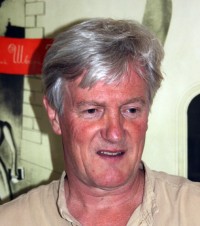

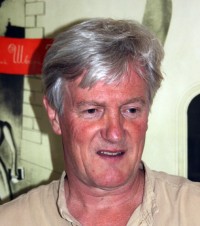

Interviewer

James Campbell was born in Glasgow and educated at Edinburgh Uni-versity. Between 1978 and 1982, he was the editor of the New Edinburgh Review. He is the author of several books of non-fiction, including Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin (1991); Paris Interzone: Richard Wright, Lolita, Boris Vian and Others on the Left Bank (1994); and This Is the Beat Generation (1999). In addition, he has edited the Picador Book of Blues and Jazz, and written a play, The Midnight Hour, which has been performed in the United States and France. He lives in London, where he works for the Times Literary Supplement.

James Campbell was born in Glasgow and educated at Edinburgh Uni-versity. Between 1978 and 1982, he was the editor of the New Edinburgh Review. He is the author of several books of non-fiction, including Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin (1991); Paris Interzone: Richard Wright, Lolita, Boris Vian and Others on the Left Bank (1994); and This Is the Beat Generation (1999). In addition, he has edited the Picador Book of Blues and Jazz, and written a play, The Midnight Hour, which has been performed in the United States and France. He lives in London, where he works for the Times Literary Supplement.

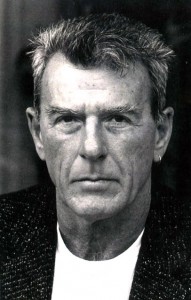

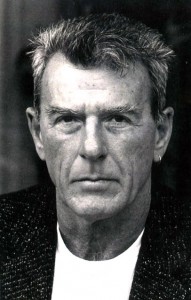

Interviewee

Thom Gunn was born in Gravesend, Kent, in August 1929, the elder son of Herbert and Ann Charlotte Gunn (née Thomson). His father was a successful journalist who, after many years spent working on provincial newspapers, moved to London, where he became editor, first of the Evening Standard, and then, somewhat later, of the Daily Sketch. Gunn’s mother had also been a journalist, but gave up her career with the births of Thom and his younger brother, Ander.

Gunn was only eight years old when the family moved to London, settling in Hampstead. He remembers the time and the place with great affection, and speaks of his boyhood as a very happy one. Just two years after the move, however, his parents were divorced. And four years after that, when Gunn was still in his mid-teens, his mother committed suicide. Asked about these events, and their effect on him, Gunn’s inclination has been to ask whether all adolescences aren’t unhappy, and to leave it at that.

Gunn’s love of reading seems to have been inspired by his mother, whose books filled the house. By the time of her death, he was immersed in the writings of Marlowe, Keats, Milton and Tennyson – to mention only the poets – and was unquestioningly committed to the idea 'of books as not just a commentary on life but as a part of its continuing activity.’

After leaving school, Gunn did two years of National Service, and then went up to Cambridge. He was twenty-one, and by his own account – and notwithstanding his precocity as a reader – ‘strangely immature’. But, surrounded by lively and challenging contemporaries – Karl Miller, John Coleman, John Mander, Tony White, and Mark Boxer, amongst them – Gunn came of age, as can be seen from the poems he began to write at this time, poems which were to make up his first book.

Fighting Terms appeared in 1954, the year after Gunn’s graduation, to considerable acclaim. ‘This is one of the few volumes of postwar verse that all serious readers of poetry need to possess and to study,’ wrote the critic, John Press, and few dissented. As Timothy Steele put it more recently: ‘Impressive for their concentration, their vigour, and their effective fusion of traditional metre with contemporary idiom, these poems established [Gunn] as one of the most arresting voices of his generation.’

While an undergraduate, Gunn met Mike Kitay, an American. After leaving Cambridge, he followed Kitay to the United States, something made possible by the award of a creative writing fellowship at Stanford University, where he became a student of the poet and critic, Yvor Winters. Except for the occasional visit, and one year-long sojourn in the mid-’60s, Gunn was never to return to England. He had decided to make America his home, and in 1960 settled in San Francisco, the city where he has lived ever since.

Eight major collections have appeared since Fighting Terms – The Sense of Movement (1957), My Sad Captains (1961), Touch (1967), Moly (1971), Jack Straw’s Castle (1976), The Passages of Joy (1982), The Man with Night Sweats (1992), and, most recently, Boss Cupid (2000). Not all of them have been as enthusiastically received as that first book, however. Especially during the ‘70s and ‘80s, when he started to write out of his experiences as a user of soft and hard drugs, and to write more openly of his life as a homosexual, there were a number of critics who felt that he was squandering his talent, indulging in what one called ‘hippy silliness’, or abandoning himself to what another called ‘vacant counter-cultural slovenliness’.

With publication of The Man with Night Sweats, a collection which memorialized friends and acquaintances who had fallen victim to AIDS, those who had come to think of Gunn as a poet who had failed to live up to his early promise were obliged to reconsider. As Neil Powell, a long-standing but not uncritical admirer, put it: ‘In [the final section of the book] Gunn restores poetry to a centrality it has often seemed close to losing, by dealing in the context of a specific human catastrophe with the great themes of life and death, coherently, intelligently, memorably. One could hardly ask for more.’

Gunn has received a large number of awards and prizes for his work, amongst them the Levinson Prize (1955), the Somerset Maugham Award (1959), an Arts Council of Great Britain Award (1959), an American Institute of Arts and Letters Grant (1964), an American Academy Grant (1964), a Rockefeller Award (1966), a Guggenheim Fellowship (1971), the W.H. Smith Award (1980), the PEN (Los Angeles) Prize for Poetry (1983), the Sara Teasdale Prize (1988), the Los Angeles Times Kirsch Award (1988), the Lila Wallace/Reader’s Digest Writer’s Award (1990), the Forward Prize (1992), the Lenore Marshall Prize (1993), and a MacArthur Fellowship (1993).

– Philip Hoy, 2000

Thom Gunn died at his home in San Francisco on April 25th 2004