Peter Dale in Conversation with Cynthia Haven

£10.95

A 137 page volume, comprising an extended interview in which Dale talks about his life and literary friendships, and more particularly about his work as a poet, translator, editor and critic. The book also contains a career sketch, a comprehensive bibliography, several pages of quotations from Dale's critics and reviewers, four recent poems and a gallery of black and white photos, as well as a colour reproduction of a portrait of Dale by the painter Mike Coleman.

Out of stock

Between The Lines

Essential reading for admirers of these poets … vigorous, illuminating and sometimes surprising adjuncts to the work itself.

— Neil Corcoran

These books enrich our contextual understanding of contemporary poetry …

— Patrick Crotty, Times Literary Supplement

A remarkably fine enterprise.

— Dana Gioia

A splendid series.

— X.J. Kennedy

Warmly recommended.

— Glyn Pursglove, Swansea Review

These conversations are skilfully presented and offer sharp new perspectives on their subjects.

— N.S. Thompson, PN Review

In the last century, we watched some of our most celebrated poets sinking into suicide, alcoholism, nervous breakdowns, and bouts of madness. You’ve said in the past that poetry is not only, as Eliot termed it, ‘a mug’s game’, but for some, a game of Russian roulette. But your life, like Richard Wilbur’s, has been eminently sane – 30 years of full-time teaching (many of them running a big department), as well as writing, editing an important poetry review, translating, raising a family, and so on. How have you managed that?

The answer seems to be that I’ve always tried to follow a saying of Dr Johnson’s to the effect that if you are idle you should not be solitary and if you are solitary you should not be idle. I became a workaholic to fend off the occupational hazard of manic depression. The second answer is that I married Pauline, a down-to-earth, eminently sane woman. Nevertheless, I think the incidence of madness among poets and of the other evils you mention may be somewhat exaggerated. One in eight hospital beds here is psychiatric, I read somewhere recently. It’s probably about the same percentage of disturbance among poets.

Perhaps I take a bit of a dismissive view of this because Alvarez in the Sixties and Seventies was pushing his theories about extremism in literature – which seemed about as far and fallacious as romanticism could go. Ian Hamilton’s introduction to the Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Poetry has more statistics about the assumed prevalence of aberrant behaviour among poets, but they don’t really show it as a necessary or majority professional qualification, though his figures, of course, only refer to mentions of such problems with poets included in the book.

Perhaps post-war influences were more unbalancing than usual, but history has always been an ongoing catalogue of horrors. Valéry’s psyche was odd enough but he remarks that everyone in the world has been happy and unhappy and that extremes of joy like those of sorrow have not been withheld from the grossest and least singing of souls. Life may be hell for more than just writers and artists and the freedom to act within those hells may be more circumscribed to most ordinary people. At the same time, one remembers Plato on madness and poets. And there may be ‘normal’ ways of being mad. An American psychologist in the Seventies remarked that anyone who appeared normal in America must be mad. You could say the same here.

In the U.S., most poets, particularly important ones, have university appointments. This system has other obvious weaknesses – Dana Gioia pointed out some in his much-attacked essay, ‘Can Poetry Matter?’ Instead, you’ve been a schoolteacher, which would certainly be an anomalous situation in the U.S., though I understand it is less so in the U.K.

A good few writers do school-teaching here, if only in their beginnings or as stop-gaps, though quite a number are full-time, as I was. Auden springs to mind, though he liked it for largely non-teaching reasons – the easy adulation of boys. If you’re a creative writer, wherever you teach or work will lead to compromises. The long vacations initially look like untrammelled time purchased for writing. It’s never as accommodating as that, but at least it’s easier than working year round in an office or factory – or chasing commissions and deadlines.

The lack of hassle over money was the biggest benefit for me. Several of my friends and contemporaries who went freelance had very difficult lives in that respect. It meant I never had to write anything I didn’t want to write. Also, I hadn’t much time to spend, as you may do when freelance, moping about over whether another poem was ever going to turn up.

University teachers may have more chance of proselytizing for their own work and sending disciples out to preach but that too has drawbacks. I was never much bothered by budding poets wanting an instant stamp of approval for their latest. The odd parent occasionally tried it.

When he was asked if he taught creative writing, Joseph Brodsky used to say, ‘No, I teach creative reading.’

That’s it. I don’t really believe you can teach or be taught creative writing. If would-be writers haven’t sufficient nous and commitment, if they don’t have that inner determination that they are writers and know what they want to achieve, then anything that a creative writing course is likely to give would merely lead them to a species of imitation. Keats said that the genius of poetry must work out its own salvation in a man. He was right. However, a good creative writing group might mend a few holes in your literary education or awareness. After all, even such an apparently simple thing as rhyme is to a large extent learnt, and not just a question of sound. There are culturally acquired components to it and it varies subtly from language to language. The structure of sonnets can be learnt but not how to write ‘Leda and the Swan’. Any aspiring writers in a creative reading group may acquire something from that type of information and may also read something new, or something old in a new light, that will make them admire and do otherwise.

In an interview with Ian Hamilton (Agenda, 31.2, 1993) you said, ‘Well, with teaching I am kept away from writing most of the time. But things happen under pressure in the mind that one’s barely conscious of, I suppose.’ That sounds rather indefinite and ‘iffy’; do you have any more definite observations about those ‘things that happen’?

The whole endeavour to make poems is ‘iffy’. The initiation of a poem seems to be largely below the level of consciousness. Sometimes, when working flat out in education and with Agenda, I’d feel a sort of mind pressure, a presentiment that a poem was ‘out there’, about to settle, and in a day or so a word or two of it, a rhythm or image would land. You learnt to make space for the landing. Who can say whether those work pressures more or less released the subconscious mind to get on with poems – prevented the literary intelligence from intervening too early? Or whether there would have been more or different poems if I had been freelance?

In the same interview, you said, ‘it’s a kind of lunatic concept to have a career poet because you can’t base a career on what is virtually a form of "luck".’

Eliot said every poem was an epitaph – hardly a career prospect. It’s what you do with that ‘luck’, the donné, that counts. No job fully protects you from the fecklessness of it. Sometimes a poem would ‘turn up’ while I was teaching. It was a rare piece of luck to be able to set the class a piece of work while enough of it could be jotted down. I like to work in absolute silence, which is hardly what a classroom has to offer. (During invigilations the odd epigram could be managed. There are about a hundred or so unpublished ones.) A poet’s luck may depend on a sort of vigilance. On the other hand, poems may be like those things forgotten in ‘senior moments’. They often come back into the head when you stop fretting about them. As I said, the biggest benefit a job gave was in not having to worry over money too much. That, I think, improved my luck.

Here’s another comment you made then: ‘Poetry isn’t subject to the will and the intention, and one has to wait and one may wait for ever and nothing come.’ It’s pretty close to the idea of inspiration and the muse, isn’t it?’

I was distantly referring to Shelley’s ‘A Defence of Poetry’: ‘A man cannot say, "I will compose poetry." The greatest poet even cannot say it; for the mind in creation is as a fading coal which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness …’ Also to Coleridge’s famous attempt to define the act of composing in Biographia Literaria, chapter 14. Then there was Keats, who said poetry should come as naturally as the leaves to the tree. All three, of course, were romantics, but the classical Valéry’s experience seems to run parallel. (Nothing said about poetry is ever a hundred-percent true. Most poets have experienced picking up an old discarded draft for lack of a donné and finding it suddenly take flight. Hardy did quite a bit of that.) Once the words start coming, the literary intelligence kicks in, and sometimes it does so too soon. But until something ‘arrives’ you just have to be patient. You can’t will a donné into existence. You have to be alert for it to surface anywhere, anyhow and any time. Trying to force it seldom works. Once arrived, as Coleridge says, it comes under the will and understanding and is retained under their irremissive, though gentle and unnoticed, control.

The Waywiser Press

Cynthia L. Haven was born in Detroit and educated at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor , where she studied with the late Joseph Brodsky and earned two prestigious Avery Hopwood Awards for Literature. After receiving her university degree, she moved to London and worked at Vogue, Index on Censorship , and a short-lived Third-World newsweekly on Fleet Street, the World Times .

Cynthia L. Haven was born in Detroit and educated at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor , where she studied with the late Joseph Brodsky and earned two prestigious Avery Hopwood Awards for Literature. After receiving her university degree, she moved to London and worked at Vogue, Index on Censorship , and a short-lived Third-World newsweekly on Fleet Street, the World Times .

Currently, she is a literary critic at the San Francisco Chronicle and writes regularly for the Times Literary Supplement, the Washington Post Bookworld, the Los Angeles Times Book Review and the Cortland Review. Her work has also been published in Civilization , Commonweal , the Kenyon Review , and the Georgia Review. Her interview with Thom Gunn appeared in the Georgia Review, spring-summer issue, 2005 . She has been affiliated with Stanford University for many years, and is a regular contributor to its magazine.

Recipient of over a dozen literary and journalistic awards, she has written several non-fiction books. Her most publications are Joseph Brodsky: Conversations (University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi, 2003/Adelphi Edizioni, Milan, 2005), Peter Dale in Conversation with Cynthia Haven (BTL, London, 2005), Czeslaw Milosz: Conversations (University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi , 2006) and "Timothy Steele in Conversation with Cynthia Haven", in Three Poets in Conversation: Dick Davis, Rachel Hadas, Timothy Steele (BTL, London, 2006).

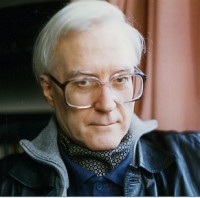

Peter Dale was born in Surrey in 1938, and educated at Strode’s School, Egham, and St Peter’s College, Oxford. For twenty-one years he was head of the English department of Hinchley Wood School, Esher, and concurrently an editor of the poetry quarterly Agenda. Well-known for his Penguin verse-translation of Villon, he has recently published a terza-rima version of Dante’s Divine Comedy and his selected poems, Edge to Edge, both with Anvil Press Poetry Ltd. His Richard Wilbur in Conversation with Peter Dale was published by Between The Lines in 2000. Revised and extended editions of his Poems of François Villon and his Poems of Jules Laforgue appeared from Anvil in 2001. He currently edits a poetry column for Oxford Today.

Excerpts

In the last century, we watched some of our most celebrated poets sinking into suicide, alcoholism, nervous breakdowns, and bouts of madness. You've said in the past that poetry is not only, as Eliot termed it, 'a mug's game', but for some, a game of Russian roulette. But your life, like Richard Wilbur's, has been eminently sane – 30 years of full-time teaching (many of them running a big department), as well as writing, editing an important poetry review, translating, raising a family, and so on. How have you managed that?

The answer seems to be that I've always tried to follow a saying of Dr Johnson's to the effect that if you are idle you should not be solitary and if you are solitary you should not be idle. I became a workaholic to fend off the occupational hazard of manic depression. The second answer is that I married Pauline, a down-to-earth, eminently sane woman. Nevertheless, I think the incidence of madness among poets and of the other evils you mention may be somewhat exaggerated. One in eight hospital beds here is psychiatric, I read somewhere recently. It's probably about the same percentage of disturbance among poets.

Perhaps I take a bit of a dismissive view of this because Alvarez in the Sixties and Seventies was pushing his theories about extremism in literature - which seemed about as far and fallacious as romanticism could go. Ian Hamilton's introduction to the Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Poetry has more statistics about the assumed prevalence of aberrant behaviour among poets, but they don't really show it as a necessary or majority professional qualification, though his figures, of course, only refer to mentions of such problems with poets included in the book.

Perhaps post-war influences were more unbalancing than usual, but history has always been an ongoing catalogue of horrors. Valéry's psyche was odd enough but he remarks that everyone in the world has been happy and unhappy and that extremes of joy like those of sorrow have not been withheld from the grossest and least singing of souls. Life may be hell for more than just writers and artists and the freedom to act within those hells may be more circumscribed to most ordinary people. At the same time, one remembers Plato on madness and poets. And there may be 'normal' ways of being mad. An American psychologist in the Seventies remarked that anyone who appeared normal in America must be mad. You could say the same here.

In the U.S., most poets, particularly important ones, have university appointments. This system has other obvious weaknesses - Dana Gioia pointed out some in his much-attacked essay, 'Can Poetry Matter?' Instead, you've been a schoolteacher, which would certainly be an anomalous situation in the U.S., though I understand it is less so in the U.K.

A good few writers do school-teaching here, if only in their beginnings or as stop-gaps, though quite a number are full-time, as I was. Auden springs to mind, though he liked it for largely non-teaching reasons - the easy adulation of boys. If you're a creative writer, wherever you teach or work will lead to compromises. The long vacations initially look like untrammelled time purchased for writing. It's never as accommodating as that, but at least it's easier than working year round in an office or factory - or chasing commissions and deadlines.

The lack of hassle over money was the biggest benefit for me. Several of my friends and contemporaries who went freelance had very difficult lives in that respect. It meant I never had to write anything I didn't want to write. Also, I hadn't much time to spend, as you may do when freelance, moping about over whether another poem was ever going to turn up.

University teachers may have more chance of proselytizing for their own work and sending disciples out to preach but that too has drawbacks. I was never much bothered by budding poets wanting an instant stamp of approval for their latest. The odd parent occasionally tried it.

When he was asked if he taught creative writing, Joseph Brodsky used to say, 'No, I teach creative reading.'

That's it. I don't really believe you can teach or be taught creative writing. If would-be writers haven't sufficient nous and commitment, if they don't have that inner determination that they are writers and know what they want to achieve, then anything that a creative writing course is likely to give would merely lead them to a species of imitation. Keats said that the genius of poetry must work out its own salvation in a man. He was right. However, a good creative writing group might mend a few holes in your literary education or awareness. After all, even such an apparently simple thing as rhyme is to a large extent learnt, and not just a question of sound. There are culturally acquired components to it and it varies subtly from language to language. The structure of sonnets can be learnt but not how to write 'Leda and the Swan'. Any aspiring writers in a creative reading group may acquire something from that type of information and may also read something new, or something old in a new light, that will make them admire and do otherwise.

In an interview with Ian Hamilton (Agenda, 31.2, 1993) you said, 'Well, with teaching I am kept away from writing most of the time. But things happen under pressure in the mind that one's barely conscious of, I suppose.' That sounds rather indefinite and 'iffy'; do you have any more definite observations about those 'things that happen'?

The whole endeavour to make poems is 'iffy'. The initiation of a poem seems to be largely below the level of consciousness. Sometimes, when working flat out in education and with Agenda, I'd feel a sort of mind pressure, a presentiment that a poem was 'out there', about to settle, and in a day or so a word or two of it, a rhythm or image would land. You learnt to make space for the landing. Who can say whether those work pressures more or less released the subconscious mind to get on with poems - prevented the literary intelligence from intervening too early? Or whether there would have been more or different poems if I had been freelance?

In the same interview, you said, 'it's a kind of lunatic concept to have a career poet because you can't base a career on what is virtually a form of "luck".'

Eliot said every poem was an epitaph - hardly a career prospect. It's what you do with that 'luck', the donné, that counts. No job fully protects you from the fecklessness of it. Sometimes a poem would 'turn up' while I was teaching. It was a rare piece of luck to be able to set the class a piece of work while enough of it could be jotted down. I like to work in absolute silence, which is hardly what a classroom has to offer. (During invigilations the odd epigram could be managed. There are about a hundred or so unpublished ones.) A poet's luck may depend on a sort of vigilance. On the other hand, poems may be like those things forgotten in 'senior moments'. They often come back into the head when you stop fretting about them. As I said, the biggest benefit a job gave was in not having to worry over money too much. That, I think, improved my luck.

Here's another comment you made then: 'Poetry isn't subject to the will and the intention, and one has to wait and one may wait for ever and nothing come.' It's pretty close to the idea of inspiration and the muse, isn't it?'

I was distantly referring to Shelley's 'A Defence of Poetry': 'A man cannot say, "I will compose poetry." The greatest poet even cannot say it; for the mind in creation is as a fading coal which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness …' Also to Coleridge's famous attempt to define the act of composing in Biographia Literaria, chapter 14. Then there was Keats, who said poetry should come as naturally as the leaves to the tree. All three, of course, were romantics, but the classical Valéry's experience seems to run parallel. (Nothing said about poetry is ever a hundred-percent true. Most poets have experienced picking up an old discarded draft for lack of a donné and finding it suddenly take flight. Hardy did quite a bit of that.) Once the words start coming, the literary intelligence kicks in, and sometimes it does so too soon. But until something 'arrives' you just have to be patient. You can't will a donné into existence. You have to be alert for it to surface anywhere, anyhow and any time. Trying to force it seldom works. Once arrived, as Coleridge says, it comes under the will and understanding and is retained under their irremissive, though gentle and unnoticed, control.

The Waywiser Press

Interviewer

Cynthia L. Haven was born in Detroit and educated at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor , where she studied with the late Joseph Brodsky and earned two prestigious Avery Hopwood Awards for Literature. After receiving her university degree, she moved to London and worked at Vogue, Index on Censorship , and a short-lived Third-World newsweekly on Fleet Street, the World Times .

Cynthia L. Haven was born in Detroit and educated at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor , where she studied with the late Joseph Brodsky and earned two prestigious Avery Hopwood Awards for Literature. After receiving her university degree, she moved to London and worked at Vogue, Index on Censorship , and a short-lived Third-World newsweekly on Fleet Street, the World Times .

Currently, she is a literary critic at the San Francisco Chronicle and writes regularly for the Times Literary Supplement, the Washington Post Bookworld, the Los Angeles Times Book Review and the Cortland Review. Her work has also been published in Civilization , Commonweal , the Kenyon Review , and the Georgia Review. Her interview with Thom Gunn appeared in the Georgia Review, spring-summer issue, 2005 . She has been affiliated with Stanford University for many years, and is a regular contributor to its magazine.

Recipient of over a dozen literary and journalistic awards, she has written several non-fiction books. Her most publications are Joseph Brodsky: Conversations (University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi, 2003/Adelphi Edizioni, Milan, 2005), Peter Dale in Conversation with Cynthia Haven (BTL, London, 2005), Czeslaw Milosz: Conversations (University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi , 2006) and "Timothy Steele in Conversation with Cynthia Haven", in Three Poets in Conversation: Dick Davis, Rachel Hadas, Timothy Steele (BTL, London, 2006).

Interviewee

Peter Dale was born in Surrey in 1938, and educated at Strode’s School, Egham, and St Peter’s College, Oxford. For twenty-one years he was head of the English department of Hinchley Wood School, Esher, and concurrently an editor of the poetry quarterly Agenda. Well-known for his Penguin verse-translation of Villon, he has recently published a terza-rima version of Dante’s Divine Comedy and his selected poems, Edge to Edge, both with Anvil Press Poetry Ltd. His Richard Wilbur in Conversation with Peter Dale was published by Between The Lines in 2000. Revised and extended editions of his Poems of François Villon and his Poems of Jules Laforgue appeared from Anvil in 2001. He currently edits a poetry column for Oxford Today.